Iraq 10 years on: The human cost

- Published

Carol Jones: "I've got to get on with my life and I do that for John."

It might be a decade since the invasion of Iraq, but for those who fought or lost loved ones the war still casts a devastating shadow.

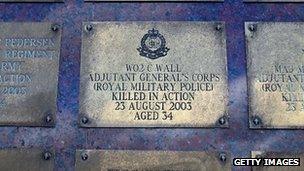

Carol Jones takes solace in visiting the Basra Memorial Wall. Even on a dull and drizzly day, the brass plaques shine gently on the granite wall, which stands in the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire.

The wall was brought back from Basra, where British soldiers had built it to honour their fallen comrades. It was re-dedicated in Staffordshire after Carol and the Royal British Legion had ensured it was brought home.

One plaque bears the name of Carol's son, Sergeant John Jones, known to his men in the 1st Battalion the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers as 'Jonah'. He died in late 2005 in Basra, after being blown up by a roadside bomb, leaving his parents, his widow Nickie, and their young son Jack - then just five years old.

"I think John was a hero, but he was my son. I didn't want him to die so early in life," says Carol. "I wanted him to come out of the Army after 22 years service and have a life. But that's all gone by the board now."

She often visits to the Arboretum to feel closer to her son. "John is buried a long way from here, but I can come here when I like. It's my second home. This place is so important to the families of the fallen."

'Have to get on'

But for Carol, the hardest times to get through - even now - are the nights.

"When I shut my eyes, that's when the brain starts working overtime, but I can't keep being maudlin and grieving. I have to get on with my life, and I have to do that for John."

She channelled her grief and her energies into campaigning for military charities, from the Royal British Legion to the military mental health charity, Combat Stress.

Carol is stoic, and wipes away the tears that come as she talks about her son in a matter-of-fact manner.

"John absolutely did love the Army, and he would say to me now if he were looking down, 'Mum, stop crying and get on with your life'. And we have, and I'm at peace with myself."

The Basra Wall honours 178 UK soldiers and one MoD civilian who died in combat operations in Iraq

So what does she think now about the Iraq war?

"I don't know about Iraq - whether there's peace there, I don't know. You see the killings on the TV news, and that hurts - because sometimes I do say that John's died for nothing.

"But if I say that, then his friends in the Army tell me off. In my eyes, I think he did, but in the eyes of his friends he didn't. So there you are," she concludes.

Today, Carol hopes that people will remember the fallen, but also think of those soldiers who survived the war with injuries, whether physical or mental.

"The people who need to be remembered most now, and helped, are the living, not the dead, especially those suffering from post traumatic stress," she says.

'Eye-opening'

One of those Iraq veterans struggling with the mental wounds of the Iraq war is Adam.

He fought in the siege of CIMIC [Civil-Military Co-operation] House in Al Amarah in Iraq in August 2004, where British soldiers came under sustained attack by Iraqi insurgents who launched more than 80 attacks over 23 days. British forces fought back by firing more than 33,000 rounds to defend the compound.

"Iraq was not a pleasant place. It was hard work. Difficult. I lost a couple of buddies out there," Adam says today. "It was eye-opening what could happen in a 500m area."

Now, Adam is trying to rebuild his life. After he left the Army his marriage broke up, he lost his home, and he was forced to give up his job.

"The signs began at work, at the job I was doing after I left the Army - aggression, depression and non-concentration.

"You get flashbacks. You do your day's graft at work, and at night you go to bed and you're exhausted by the morning because all night you've just done a patrol or whatever. It's draining," he says.

Today, Adam has at last found two therapists able to help him, after he reluctantly had to give up work two years ago, when his bosses were unable to give him time off to seek the assistance he needed.

One of his therapists, Sun Tui, has been helping Adam with a unique form of animal therapy, which helps ease trauma by using interaction with horses.

How equine assisted therapy is helping Adam rehabilitate

She is the founder of the International Foundation of Equine Assisted Learning (IFEAL), which has already helped other former soldiers.

"It's amazing, but you don't think about anything other than making that connection with the beast," says Adam, who has visibly relaxed over the course of a session.

"I have never been a horse person, but this brings you out of that depression and loss, and shows you that all is not lost."

Now Adam, 45, wants to focus on getting better, finding a home and getting his life back on track - and perhaps one day, become a mentor to others in the same situation.

"There is a certain amount of help and a lot of infrastructure in place for physical injuries. But for guys with a mental problem, there's not a lot there at all, so you're left out on a limb," he says.

During the Iraq war, official figures show that 73 servicemen or women were very seriously injured, and another 149 seriously injured. Between 2006 and the war's end in 2009, MOD statistics record that some 315 UK service-personnel were wounded in action.

Charities such as Help for Heroes as well as the older, more established military funds such as the Royal British Legion, the Soldiers' Charity, Blesma (British Limbless Ex Service Men's Association) and others are helping veterans who need assistance, especially with prosthetics or rehabilitation for physical injuries.

But nobody knows for sure how many still bear the mental wounds of the Iraq war - nor how many more veterans will come forward for help in the years to come, while others struggle alone.

- Published17 March 2013

- Published12 March 2013

- Published17 March 2013