Why one criminal stopped offending

- Published

Munday is now a family man who is trying to help others stay out of prison

For most of his life, Roy Munday says, he was at war with authority.

An armed robber, a drug dealer and a man who beat people up for money, he spent a total of 17 years in prison.

He said that at one time he was deemed so violent he came close to being kicked out of the mainstream prison system and sent to Broadmoor high-security hospital.

But today, Munday is a family man and a university graduate. Now 45 years old, he's still physically imposing but is trying to use his mistakes to help others.

He is currently a volunteer with the St Giles Trust, a charity that uses ex-offenders to try to help recently released prisoners so they can avoid going back to jail.

Cost of reoffending

He blames his childhood for turning him into the "angry and bitter" youth and adult he became.

He said his mother had tried to kill him three times by the time he was 12. He had been in and out of care since the age of four and had suffered physical and emotional abuse that led him to run away countless times.

Crime for him, he says, was about survival.

And like many others, he spent years going in and out of prison.

He was last released nine years ago and credits the St Giles Trust with giving him the opportunity to finally start building a career.

According to the National Audit Office, the cost of crime committed by previous offenders is estimated to be up to £13bn per year.

The latest quarterly local reoffending figures released by the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) showed there was a mixed picture across the country. While five regions - East Midlands, London, North East, West Midlands and Yorkshire & Humberside - saw a significant reduction in reoffending, Probation trusts in Hertfordshire, Lancashire, and Surrey and Sussex had significant increases in reoffending.

Overall, MoJ's figures show that 47% of offenders who leave prison go on to commit further crime within a year.

It's a problem that Justice Secretary Chris Grayling has said he wants to address.

Under new plans, prisoners who have served less than 12 months would start to receive support on leaving prison and probation services would be changed to a payment-by-results system.

Alongside private providers, it is hoped that charities such as the St Giles Trust and ex-offenders like Munday can help bring reoffending rates down.

As yet, though, there are no details on how they would be paid for results and what the criteria would be.

The Institute for Government's Tom Gash, who was a crime policy adviser to Tony Blair's government, told the BBC that Mr Grayling's set of reforms was ambitious.

"By outsourcing a service that's never been outsourced before he's trying to introduce a new way of paying for those services with payment for results, which is very complicated, particularly in this area where it's hard to measure the impact that providers have on people's reoffending," he said.

"He's also trying to do this without spending any more money and, in fact, trying to deal with maybe up to twice as many people."

In a recent report, the think tank Policy Exchange said the government was right to make changes and made recommendations including the creation of prison league tables to see which had the lowest rates of reoffending.

Wake-up call

The difficulty of trying to help former prisoners was clear to see on an afternoon at the St Giles Trust's headquarters in south London.

Munday had a meeting booked with a man who had recently been released from prison for being in possession of a knife but he failed to turn up.

While in prison the man had asked for help applying for housing and benefits.

When Munday called him he didn't answer his phone. He had missed every meeting in the six weeks since his release.

Munday says he and other ex-offenders can make a difference, but it is important for prisoners like the young man who missed his appointments to need to "want to help themselves".

No one method of rehabilitation has ever been proved to completely eradicate reoffending in any country.

Munday said the wake-up call for him was when a prison officer who knew him as a young man heard he was going to be transferred from Wormwood Scrubs to Broadmoor.

He offered him the option of entering the therapeutic unit for violent offenders at Wormwood Scrubs rather than going to Broadmoor.

"It made me sit there and think that at 15 years old I was in a position where no school wanted to take me, and then I was in the same situation in the prison system.

"It looked like in that 20-year period, absolutely nothing's changed in my life. It's just got progressively worse and I've progressed to this point where I am such a bad person that even the prisons can't handle me."

'Stake in society'

The two years he spent in intensive group therapy helped him confront the abuse he suffered in childhood and start making changes in his life.

He started working for qualifications in the prison gym and, for the first time, imagined a life without crime.

Towards the end of his sentence as an open prisoner, he was able to complete a degree in sport and exercise science.

He was finally released in 2004 after serving more than 10 years for armed robbery, possession of a firearm and intimidation of witnesses.

But he had to find his own accommodation on his first night out of prison with no help from anyone.

That many prisoners leave with only £46 in their pocket and nowhere to go is one of the reasons Munday cites for prisoners turning back to crime.

"Make sure they've got somewhere to go when they are actually released, deal with it whilst they are still in prison, get their benefits while they are still in prison, because you've got people walking out the gate - they've got nowhere to go.

"They are being set up to fail straight away," he said.

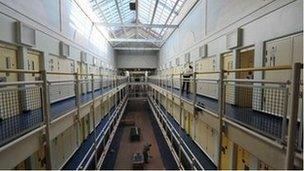

Munday spent a number of years in Wormwood Scrubs prison

Dr Thom Brooks of Durham University, who has written books about crime and punishment, says people are far less likely to commit crime if they see themselves "as having a stake in society".

Munday agrees: "We need housing, we need jobs, but most of all people need food and they need to feel part of something."

Policy Exchange agrees that housing is essential, but that the establishment of real work in prison, literacy and numeracy courses and a major clampdown on drugs in prison are vital too.

Munday believes ex-prisoners like him and organisations such as St Giles can make a difference to the lives of prisoners and stop them reoffending - which is in everyone's interest.

"I'm not the greatest role model in the world and I've made a lot more mistakes than most, but despite that I still made the changes in my life.

"I've got a house, I've got a family I love and who love me and I might not have the finances or everything else but I'm quite relaxed with my life now."

- Published9 May 2013

- Published9 May 2013

- Published9 May 2013