Roma migrants: Could UK do more to integrate them?

- Published

Residents in Page Hall are uncomfortable with the Roma culture of congregating in the street in large groups to chat

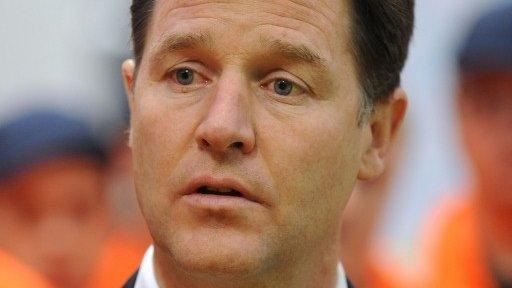

Last month, David Blunkett aired the grievances of some of his Sheffield constituents unhappy at the behaviour of their Roma neighbours.

But with recent research estimating the number of Britain's Roma now at 200,000 people, what is being done to smooth over the tensions between the Roma and their more established neighbours?

Other communities are also struggling to cope with an influx of east European migrant Roma, many living in poverty in overcrowded houses.

The government doesn't assess the size of the Roma population, and leaves it to local communities to help them integrate, but says it has a strategy that addresses the "pull" factors that bring people here and supports English language training for those already here.

Rat traps

For David Blunkett, that's not enough.

"We're on the edge of an explosion of feeling," he told BBC Radio 4's The Report. "We can actually make this work, but we can't if people are fearful that nobody's listening to them and nobody's responding."

On the terraced streets of Page Hall in Sheffield, residents welcome David Blunkett's intervention.

People there complained of rats, rubbish and noisy crowds on the streets late into the night. But what we didn't find was criminal behaviour, overt racism, nor the threat of violence.

Long-term residents sympathised with the overcrowded living conditions their new neighbours endured, although they were uncomfortable with the Roma culture of congregating in the street in large groups to chat.

Instead, their anger was directed at the authorities who, they said, had done too little to help the Roma integrate and prosper, leaving both communities "abandoned".

"The problems round here, I lay the blame squarely on the shoulders of the council," said Linda Gill, who showed us the rat traps she'd had to lay in the garden of her neat semi.

"It's happened suddenly and from nowhere. People now don't want to live in this area."

We met Oliver, a young Roma man who has lived in the city for 10 years, who sympathised with his white British and Pakistani British neighbours, but insisted not all of Page Hall's Roma struggled with the way most people dispose of their rubbish.

Sheffield City Council wouldn't talk to us, but we did discover they were doing work behind the scenes - such as extra refuse collection and Roma-friendly careers advice - to ease tensions.

'Pot of tension'

Glasgow City Council was more open. The city, which is home to a similar number of Slovakian Roma as Page Hall, has poured resources into schemes to ease integration and to deal with the environmental impact on the multicultural district of Govanhill, which has seen its population almost double in 10 years.

Despite this, the tensions in the local community were not dissimilar to Sheffield.

Jade Ansari, of the newly formed Restore Govanhill residents' group, spoke about desperate overcrowding in the area's tenement blocks - sometimes with families of 15 in two-bedroom flats - and showed me evidence of the fly-tipping, infestation and crowds on the street that were the result.

"It's a big, bubbling pot of tension and something has to be done before it gets too much," she said. A walk around the district's main shopping street illustrated her point. Abandoned fridges and bags of rubbish could be found every few yards along Allison Street.

The European Union has threatened France with legal action over its handling of the expulsion of Roma migrants

But again racism was hard to find. There was, however, frustration at the impact the new arrivals' lifestyles had on them and their inability to communicate.

Perhaps it was this lack of personal hostility that has helped people like Vera and Yarov call Glasgow home.

"I've been here for six years. My family is happy here - we're planning to stay here. We feel this is the country where we want to stay and we want to make the effort to become good citizens," said Vera.

For them, meaningful work - and a community centre to replace the street-corner gathering places - is what they would like to have.

Glasgow City Council admitted its previous efforts, although extensive, had tackled only the symptoms of the problems Govanhill had experienced over the past few years.

While I was in the city, the council announced plans to take more decisive action. A £32m plan to purchase the worst of the slum tenements housing Roma people and hand them over to a housing association would, the council said, tackle the root of the problem.

But Glasgow's approach is relatively expensive. Hard-pressed councils in England may struggle to find similar sums to alleviate their own problems.

And current UK government policy on migration in England puts the responsibility squarely on the shoulders of local communities, saying it will act only "exceptionally" when community cohesion is challenged.

While the government wouldn't be interviewed for our programme, it did say it had addressed the "pull" factors on migration and had recently detailed plans to tackle benefit tourism and the abuse of free movement rights within the European Union.

Dave Brown heads Migration Yorkshire, a body that advises the region's councils on migration issues. He said the community stresses caused by the unique challenge of Roma migration needed outside help.

"Sometimes there is nothing wrong with the government stepping in. It will come back and bite them if they don't," he said.

"We're not saying there will be riots, what we're saying is once a group is excluded, where there is the discrimination and the stereotyping we've seen over centuries in Europe, if we import that, it will take years or decades to overturn - this is the type of thing we cannot afford to let happen in the UK."

The Report by Andrew Fletcher was first broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on Thursday 12 December at 20:00 GMT.

- Published14 November 2013

- Published14 November 2013

- Published12 November 2013

- Published28 November 2014

- Published2 December 2013