Christine Keeler obituary: Life of the Profumo scandal model

- Published

Christine Keeler found herself at the centre of an affair that rocked the British establishment.

The revelations about her relationship with the cabinet minister John Profumo hastened the end of the Macmillan government.

The resulting scandal, involving allegations of espionage and prostitution, and a dramatic court case, saw her pilloried in the tabloid press.

But Keeler was a somewhat naive victim of an establishment that was determined to protect its own position against what it saw as a tide of permissiveness.

Christine Keeler was born in Uxbridge, west London, on 22 February 1942.

Her father deserted the family while she was still a young child and her mother later set up home with Edward Huish, in a pair of converted railway carriages near Windsor.

She was sexually abused as a teenager both by her mother's lover and his friends, for whom she babysat.

She suffered an abusive childhood

Keeler left school with no qualifications and had a succession of jobs, including working in a gown showroom and a spell as a waitress. She also posed for some modelling pictures.

Platonic friendship

At the age of 17 she became pregnant. Attempts at a self-induced abortion failed but the child, a boy, died days after the birth.

"I was just 17, I did not have many illusions left, and the ones that did remain were soon to vanish."

Keeler found a job in Murray's, a Soho nightclub, where she served drinks and posed semi-naked on the stage. She also befriended another model, Mandy Rice-Davies.

"When we weren't on stage, we were allowed to sit out with the audience for a hostess fee of £5," she later wrote.

By her own account she, like a number of the girls, had sexual relationships with the club's clients, although it was officially forbidden by the management.

Her relationship with Stephen Ward was platonic

It was at Murray's that she met Stephen Ward, an osteopath who had a client list that included a number of rich and important people, including the former Conservative MP Viscount Astor.

Keeler moved into Ward's flat although the couple maintained a platonic friendship.

Ward took Keeler to parties where he introduced her to many of his friends including Peter Rachman, the notorious slum landlord, with whom she had a relationship.

Ward and Keeler were also frequent attendees at weekend parties at the Astors' Cliveden estate in Buckinghamshire.

Dismissed

At one of these events, on 8 July 1961, Keeler, splashing in the swimming pool, caught the attention of John Profumo, then Secretary of State for War.

Profumo, who was married to the actress Valerie Hobson, was seen as one of the government's rising stars. He kept in touch with Keeler and the pair had a brief affair.

Also at the party was Eugene Ivanov, assistant naval attaché at the Soviet Embassy, who was friendly with Ward.

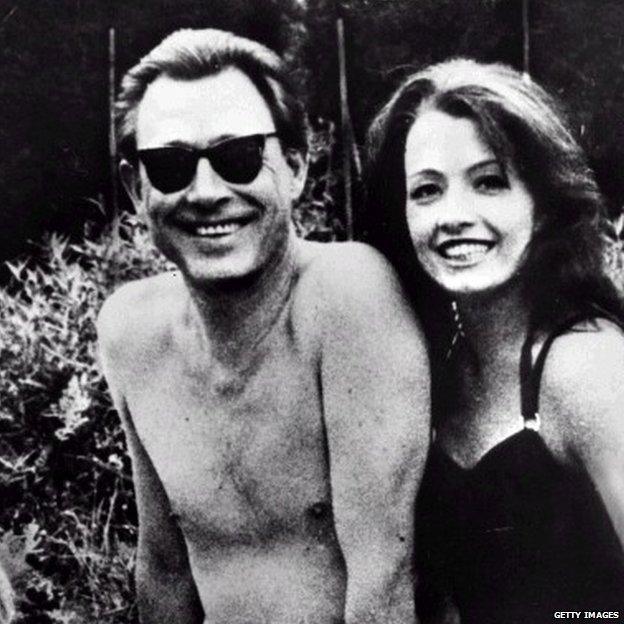

John Profumo, here with his wife Valerie Hobson, was seen as a rising political star

Keeler later claimed she had been sleeping with Ivanov at the same time as she was having an affair with Profumo, but many commentators have since dismissed her account.

She had also been having relationships with two other men, Lucky Gordon and Johnny Edgecombe.

Gordon and Edgecombe quarrelled bitterly over Keeler, resulting in Edgecombe firing shots at a flat where Keeler was hiding.

The subsequent police investigation led the press to take an interest, and reporters soon learned of Keeler's relationship with Profumo.

'No impropriety'

Suspicions that Keeler had obtained secrets from Profumo and passed them to Ivanov, led Labour to decide the whole matter was a security issue.

With the press unwilling to risk a libel suit by publishing the story, Labour MP George Wigg used parliamentary privilege to accuse Profumo of having an affair with Keeler.

Profumo was forced to come to the House where he denied having sexual relations with Keeler.

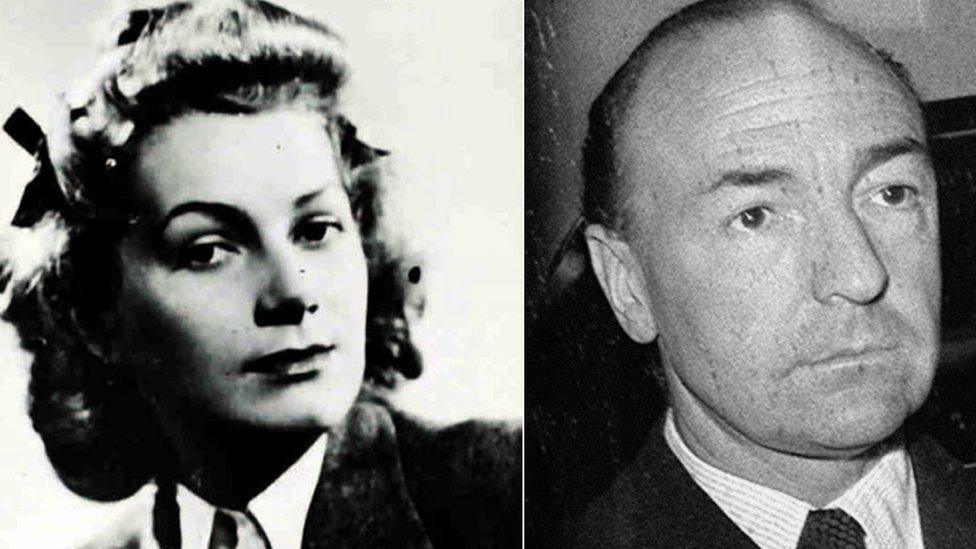

Stephen Ward was not destined to hear the verdict at his trial

"Miss Keeler and I were on friendly terms," he told fellow MPs. "There was no impropriety whatsoever in my acquaintanceship with Miss Keeler."

Meanwhile, Keeler had testified at the trial of Lucky Gordon, who she claimed had assaulted her. He was jailed for three years.

On 5 June, Profumo resigned as Secretary of State for War, having admitted that he had lied to the House of Commons about his relationship with Keeler.

Perjury

Stephen Ward was arrested and accused of living on Keeler's immoral earnings. His trial began at the Old Bailey in July 1963.

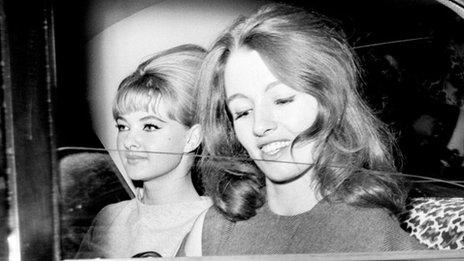

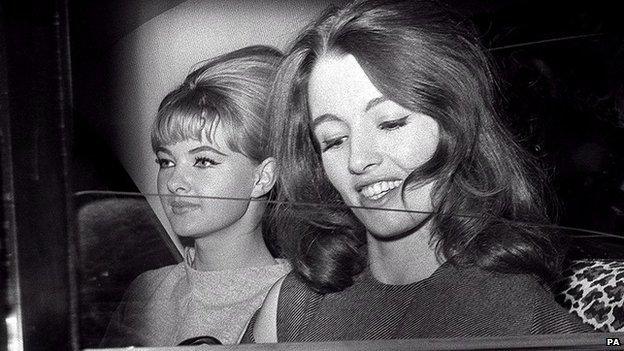

Mandy Rice-Davies (l) was, with Keeler, a key witness in Ward's trial

In what the writer Ludovic Kennedy described as a blatant miscarriage of justice, Ward was convicted following a devastating summing up by the trial judge.

But, by the time the jury announced its verdict, Ward was in a coma, having taken an overdose of sleeping pills. He died in hospital three days later.

In December 1963 Lucky Gordon's sentence was overturned by the Court of Appeal, and Keeler was accused of lying at his trial.

She pleaded guilty to charges of perjury, and was sentenced to nine months in prison.

Scandal

Labour won the 1964 General Election, having used the Profumo affair to accuse the Conservatives of being unfit to govern.

On her release from prison, Christine Keeler largely disappeared from the public eye.

There were two marriages which did not last, but did produce two children.

She had little time for a fusty establishment

Much of the money she had been paid by newspapers had disappeared by the 1970s.

She published five books about her life, one of which, entitled Scandal, was the basis for the 1989 film of the same name, which starred Joanne Whalley as Keeler.

As a young woman, Christine Keeler was desperate to get away from an unhappy home and make something of herself. She had little time for the fusty morals of a traditional establishment class.

Unfortunately for her, that class was desperate to maintain its influence in a country about to experience the dawn of the huge social changes of the 1960s.

That establishment was aided and abetted by a tabloid press, desperate to expose scandal, even where it didn't exist, just to maintain circulation.

"They wanted to hear about the sex of course," she once said bitterly. "But not the rest. No one wanted to hear the rest."

- Published28 November 2017

- Published19 December 2014