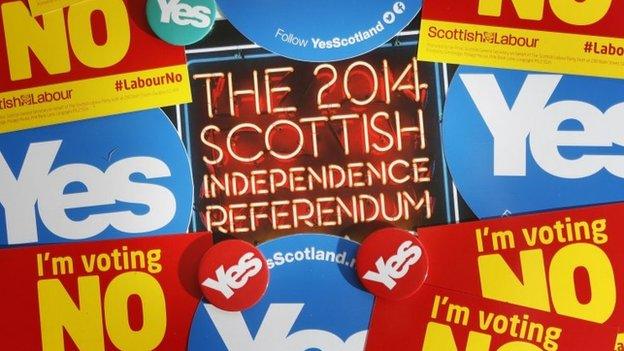

Scotland votes 'No': How the 'No' side won the referendum

- Published

Scotland has voted No to independence in a referendum, meaning its 300-year old union with the UK will continue. So how did the No campaign win?

The No side had a head a start

1. They were always the favourites

The No camp had a head start. When the Edinburgh Agreement was signed on 15 October 2012, paving the way for a referendum in 2014, polls suggested about a third of Scotland's 4.2m voters wanted independence.

A plethora of polls over the next 18 months consistently put the No camp ahead.

In June - by which time there had been 65 opinion polls - all bar one had put the No side in the lead, according to, external polling expert Professor John Curtice.

"The No side were always favourites to win, which is why the YouGov poll for the Sunday Times, external which put the Yes vote ahead about 10 days ago created such an upset," he says.

Happily for the No side, most of the following polls put them back in the lead again and they were able to finish ahead of the underdogs on polling day.

One in three Scots say they are "equally Scottish and British"

2. The Scottish feel British

A resurgence of Britishness - either caused by, or coinciding with the referendum - is credited with giving the pro-union No campaign a boost.

The number of people living in Scotland who chose British as their national identity rose from 15% in 2011 to 23% in 2014, according to the Scottish Social Attitudes Survey., external The number of people who chose Scottish fell from 75% to 65% over the same period.

However, there is also evidence that the rising tide of British sentiment in Scotland has taken place over a longer timescale.

Almost one third of Scots now say they are "equally Scottish and British" - the highest proportion since former Labour PM Tony Blair came to office in 1997, according to the survey. Less than one in four describe themselves as "Scottish not British".

"At the end of the day, Scotland still feels moderately British," says Prof Curtice.

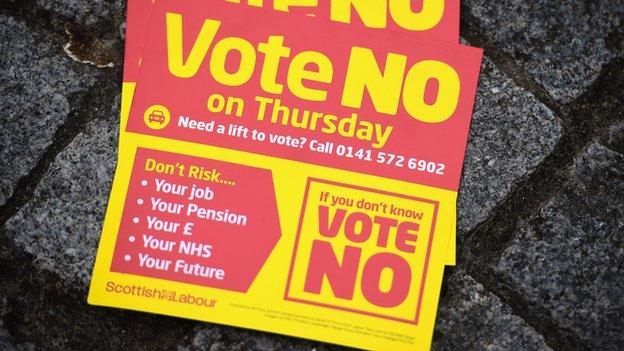

No leaflets often emphasised risks such as pensions, jobs and money

3. The risk factor

The No campaign came under fire from the Yes campaign for being negative, with some dubbing it "Project Fear".

However, the No vote suggests Better Together was successful in "drawing people back from the prospect of taking a risk that was not necessary," according to Prof Curtice. Just two days ahead of the polls, voters were twice as likely (49%) to regard independence as a risk than staying in the Union (25%), he says.

In April, Scotland's First Minster Alex Salmond called the No campaign "the most miserable, negative, depressing and thoroughly boring" in modern times. In contrast, he said the "Yes" campaign was "positive, uplifting and hopeful".

More recently the leader of the SNP criticised the "scaremongering" of No, saying the Yes side was "determined to focus on opportunity".

The Better Together campaign always denied being too negative, saying the campaign was a positive one, emphasising what the union had achieved with Scotland in it, and how much more could be done when the UK "stands together".

However, it often accused Mr Salmond of not giving answers, with Mr Darling saying voters were "very alive to the risks" and uncertainty of independence.

Earlier this week, UK Prime Minister David Cameron told Scottish voters it was his "duty" to warn them of the stark costs of a "painful divorce".

What the 'No' vote means for Scotland and rest of the UK

.gif)

The YouGov poll for the Sunday Times suggested that 51% planned to back independence

4. They stemmed the Yes surge

The Sunday Times YouGov poll, external which put the Yes camp in the lead 10 days ago led to a surge of momentum, and increased mobilisation, in the Yes camp. Suddenly the prospect of a victory was in sight.

The response of the No camp was swift. Mr Cameron and labour leader Ed Miliband skipped their weekly Prime Minister's Questions clash to travel to Scotland. Lib Dem leader Nick Clegg went too. The Saltire was flown above Downing Street.

Former prime minister Gordon Brown, who has high approval ratings in Scotland, set out a timetable for boosting the Scottish Parliament's powers if voters reject independence, promising a draft new law for a new Scotland Act would be published in January.

Then came "the vow" to devolve more powers and preserve the Barnett funding formula if Scotland voted No.

Prof Curtice says the interventions of "the three wise men heading north" didn't really change people's opinions of devolution, or their view on the referendum. It did yield an eight point rise in those who thought Scotland would get more more powers though, he says.

What the No campaign's final actions successfully managed was to halt the momentum of the Yes campaign. "It stemmed the tide," he says.

Currency was a key issue in the referendum debate

5. For richer, for poorer?

This was one of the biggest questions for voters, if not the biggest question.

Both sides battled hard over the economy, with claims and counter-claims over currency, oil and business playing a big part of the debate. The No vote suggests Scots were not convinced that an independent Scotland would be better off.

The pound was at the heart of the disagreement, with the Scottish government consistently stressing a currency union would be in the "best interest" of both Scotland and the rest of the UK - something the UK government strenuously rejected, along with a currency union.

How much of the North Sea oil it would be entitled to - and what it might be worth - and the future of financial institutions and businesses north of the border were also the subject of heated discussion.

So was the amount of money in people's wallets. The Scottish government calculated that "each Scot would be £1,000 better off" after 15 years. However the UK Treasury claimed Scotland, as part of the UK, would be able to have lower tax or higher spending than under independence. This "UK Dividend" is estimated to be worth £1,400 per person in Scotland in each year from 2016-17 onwards.

Ultimately, no-one knows whether an independent Scotland will be better off or not. There are too many variables on issues such as productivity, tax and employment levels.

But the No vote suggests people in Scotland were more persuaded by Better Together's arguments.

6. Their voters voted

The turnout in areas that voted No was high

Turnout - which was 84.5% across Scotland - was generally higher in No areas than Yes areas.

Particular highs were recorded in East Dunbartonshire (91%), East Renfrewshire (90.4%) and Stirling (90.1%) - which rejected independence by 61.20%, 63.19% and 59.77% respectively.

Relatively fewer people went to the polls in the urban strongholds where Yes Scotland was relying upon large numbers of supporters to turn out - such as Glasgow, where the turnout was 75%, and Dundee, where the turnout was 78.8%. They voted in favour of independence by 53.49% and 57.35% respectively.

Prof Curtice says the No support in different council areas was also in line with some of the expectations about the kinds of places in which the No campaign would do relatively well.

The No vote averaged 64% in areas where more than 12% of the population was born in the rest of the UK, compared with 53% in those where less than 8% were born elsewhere in the UK.

It averaged 61% in places where more than 24% of the population were aged 65 and over, compared with 51% where less than 21% were over 65 and over.

And the No vote was higher in the more rural half of Scotland - 60% - than in the more urban half, where it averaged 53%, according to John Curtice.

The No vote also averaged 60% in councils where more than 30% of the population were professional and managerial, compared with 51% where less than 26% were in professional managerial occupations, he added.