Scotland votes 'No': What happens now?

- Published

During the referendum campaign parties signed a pledge to devolve more powers to Scotland if they rejected independence.

Scotland has voted "No" to independence in the historic referendum on the nation's future.

For now, that means it will continue to form an integral part of the UK - but for Scottish devolution, the process of granting powers from Westminster to the Scottish parliament, it's far from business as usual.

The focus will now be on how the UK government delivers its promise of more powers for the Scottish parliament, based at Holyrood, Edinburgh.

Here's what's likely to happen next.

More power

The three biggest UK-wide political parties - The Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats - agree that further devolution of powers to Holyrood must take place. During the referendum campaign, the parties signed a pledge to devolve more powers to Scotland, if Scots rejected independence.

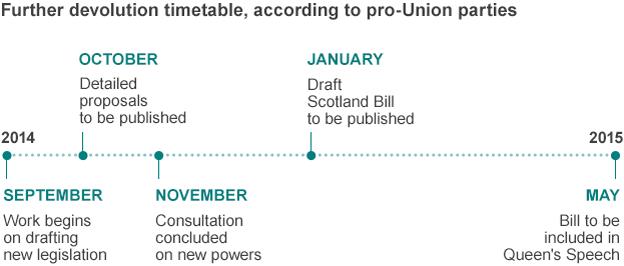

A timetable to deliver change was set out by former prime minister - and Scottish MP - Gordon Brown. It was quickly endorsed by the UK-wide parties.

Immediately after the result became clear, Prime Minister David Cameron aimed to show the UK government was grabbing the initiative by announcing Lord Smith of Kelvin, a former BBC governor, to oversee the implementation of more devolution on tax, spending and welfare.

He said draft legislation would be ready by January, as per the timetable laid out by Brown.

Under the former PM's proposals, a "command paper" would be published by the present UK government setting out all the proposals by the end of October.

A white paper would be drawn up by the end of November, after a period of consultation, setting out the proposed powers.

A draft new "Scotland Act" law would be published by Burns Night (25 January) 2015 ready for the House of Commons to vote on.

However, with a UK general election due in May 2015, the legislation would not be passed until the new parliament began.

Party differences

The Scottish Parliament is currently funded through a block grant and the amount it gets is defined by the Barnett Formula - an arrangement for adjusting funds to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to spend on devolved policy areas, on the basis of population . All three parties are committed to preserving the essence of this mechanism in some form.

And in proposals set out by the parties earlier this year, each offered Holyrood considerably more income tax-raising powers than the Scottish parliament has at present. However, there were significant differences between the parties in the proposed extent of those changes.

What the 'No' vote means for Scotland and rest of the UK

.gif)

Labour wants to give Holyrood the power to vary income tax by 15p in the pound - but not the power to cut the top tax rate on its own.

The Conservatives propose to give Scotland total control over income tax rates and bands. Holyrood would also be accountable for 40% of the money it spent.

The Liberal Democrats propose giving Scotland power over income tax, inheritance and capital gains tax. The party has also touted scrapping the Act of Union between Scotland and England and replacing it with a declaration of federalism.

None of this will suffice for the Scottish National Party, but just as the Edinburgh Agreement, committed Prime Minister David Cameron to honouring the referendum result, the same is true for the Scottish first minister.

The Scottish government is expected to fight for a "devo max" - essentially far-reaching devolution - package of powers, likely to include total control over income tax, corporation tax, and air passenger duty, and extensive control over welfare.

The negotiations

UK political parties will have to work through their differences, and come up with a single proposal. But others will also be involved.

In the lead up to the establishment of the Scottish Parliament in 1999, the UK government laid out its devolved responsibilities in a White Paper in July 1997, before they were backed by voters and put into legislation.

Credit for paving the road towards Scottish devolution was given to the Scottish Constitutional Convention, an association of Scottish political parties, churches and other civic groups set up in 1989.

Lord Smith's new body on finalising Holyrood's new powers could in some ways be seen as a modern-day version of the organisation.

SNP future

Nicola Sturgeon could be in the running to take over from Alex Salmond

So what now for the SNP?

In the immediate future, it's back to government - the job to which the SNP was elected by a landslide at the last Scottish Parliament election.

But, following the "No" vote, Mr Salmond announced he would step down as SNP leader and first minister at the SNP's annual conference in November.

There will now be an SNP leadership contest - these are known for being interesting, external - with Deputy First Minister Nicola Sturgeon the clear frontrunner.

But might we see former leadership challengers Mike Russell, Alex Neil and Roseanna Cunningham - all now members of the Scottish government - also throw their hats in the ring?

John Swinney though, Scotland's finance secretary, has ruled out a return to the leadership, a job he held between 2000 and 2004.

And, for a party which hasn't always had the most harmonious existence, the SNP's shown a remarkable level of discipline since winning office in 2007 - but could that now be in jeopardy?

However, given the scale of the SNP's last election victory, it is quite possible the party will win the next Scottish parliament election, especially if voters feel Labour has not done enough to win back their trust as a party of government.

Rest of the UK

With increased devolution of powers to Holyrood, many will want to address the so-called West Lothian question: is it fair that English MPs have no say on devolved issues in Scotland, but Scottish MPs at Westminster can still vote on the same issues as they affect England?

A recent poll by YouGov for the Herald suggested 62% of English people, external believe Scottish MPs should be banned from voting on England-only laws.

Many in Wales and Northern Ireland will also ask whether they should be getting more powers too.

The other issue for Wales is the continuation of the Barnett funding formula, which sees Scotland get more spending per head than the UK average.

Plaid Cymru says the arrangement would leave Wales £300m poorer each year, while Labour has promised to address the issue if it wins the 2015 UK election.