Scotland votes No: How the UK could now change

- Published

A Parliament for the UK - seen here specially lit for the 2012 Olympics

Scotland has voted "No" to independence. But what could still change for the UK as a whole as a result?

From early on this year, all three of the largest parties at Westminster promised more powers for Scotland if voters chose for Scotland to remain part of the UK.

In the closing weeks of the campaign, the pro-Union parties appeared to step their appeals up a notch, setting out a timetable for more powers to be transferred to Scotland and agreeing a pledge on key commitments for more devolution.

The Yes campaign and Scottish government responded at the time that the only way to guarantee more powers was to vote for independence.

But further devolution will not just affect Scotland. It has implications for politics across the rest of the UK too. Here are five possible ones:

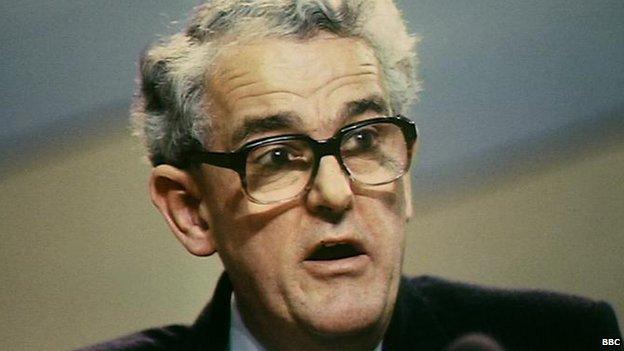

Labour MP Tam Dalyell first raised the West Lothian question in 1977 and it has not been answered yet

1. 'West Lothian Max'

One major peculiarity of British politics - known as the West Lothian question - was first identified by Labour MP Tam Dalyell in 1977.

In a devolved system, Scottish MPs can vote on policies covering things like schools and hospitals in England, but English MPs have no say on how these are run in Scotland because the Scottish Parliament takes care of them, which has raised questions of fairness.

If more responsibilities are handed to Holyrood, there will be more devolved areas on which English MPs cannot vote, while there are no such restrictions on Scottish (and Welsh and Northern Irish) MPs. It's "West Lothian Max", if you like.

The McKay Commission, external, set up by the government in 2012, found more should be done to ensure laws affecting England had the support of a majority of MPs for English constituencies.

But little more was said on the subject until the three largest Westminster parties united on a promise for more devolution to Holyrood.

Shortly afterwards Prime Minister David Cameron hinted that English MPs could get the final say on laws affecting England only, although he ruled out the option favoured by some Conservative backbenchers of setting up and English parliament.

What the 'No' vote means for Scotland and rest of the UK

.gif)

The question certainly seems to be a big concern for voters.

A recent poll by YouGov for the Herald suggested 62% of English people, external believe Scottish MPs should be banned from voting on England-only laws. The latest British Social Attitudes report, external came up with a similar percentage, and showed the proportion who felt this way had risen over the past decade.

HM Treasury on Whitehall, London - where grants to Holyrood, Stormont and Cardiff Bay are decided.

2. The Barnett formula

Another problem which has foxed MPs for more than 30 years is the Barnett formula. It was devised in 1979 as a way of adjusting block grants to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to spend on devolved policy areas, on the basis of population.

Scotland currently receives more spending per head than the UK average - but some argue there are good reasons for this, such as the difficulty of providing services to remote communities.

The largest Westminster parties have long agreed a "No" vote should lead to more tax-raising powers for Scotland, potentially creating a situation where it gains greater control over its own revenues but retains Barnett money.

The pledge signed by party leaders more recently included a commitment to preserve the Barnett formula.

It is not yet clear whether, under the joint pledge, the pro-Union parties envisage the block grant being reduced to offset revenue gained through new tax-raising powers for Holyrood, as was originally specified in the Labour Party's commission on devolution, external.

Although it seems likelier than ever that the Barnett formula will endure, polls indicate many English people see the arrangement as unfair.

The British Social Attitudes survey, external suggested 44% of people feel Scotland gets more than its fair share of public spending.

The Herald/YouGov poll suggested that if there is a "No" vote, 56% of voters in England believe levels of public spending in Scotland should be reduced to the UK average.

Alan Trench, professor of politics at Queen's University Belfast and author of the Devolution Matters, external blog, says existing tensions in the system could become worse if there is further devolution and the Barnett formula is retained.

Seats of (more) power? The Senedd building in Cardiff and Stormont Castle in Belfast.

3. Wales and Northern Ireland

If Scotland gets more powers, another obvious question is whether Wales and Northern Ireland will want them too.

In Wales, Plaid Cymru's Treasury spokesman, Jonathan Edwards MP, said earlier this month: "Whatever the result in Scotland, any Westminster government that ignores the immediate need for greater powers all round for the nations of these islands is only burying its head in the sand."

Plaid Cymru has since been joined in those calls by the Wales' first minister, Labour's Carwyn Jones, who told the BBC: "What is on offer [to Scotland] should be offered to Wales. It's a matter then to judge what is best for Wales.

Martin Shipton, chief reporter for the Western Mail, says a "No" vote in Scotland could create concern over "the fear that Scotland would get more job-creating powers and put Wales at a disadvantage".

But this does not necessarily translate into clear support for strengthening the Welsh Assembly, he says, since "people in Wales know the economy is relatively weak and has a small tax base - they would be worried that it would lead to higher taxes".

Calls for further Welsh devolution have been muted by "a perception of issues with delivery of services" in devolved areas such as health and education and the difficulty Plaid Cymru has had in rallying the kind of support the SNP has enjoyed, according to Shipton.

In Northern Ireland, it would be impossible for one pro-devolution party to dominate the assembly as the SNP has done in Scotland, since legally there can be no majority at Stormont.

Tony Grew, a reporter for PoliticsHome and the Belfast Telegraph, says that he doesn't think there is a widespread call for more devolution.

"The argument in Scotland is often centred on the economy, but in Northern Ireland it's clear where the subsidies are coming from. It's very difficult to make a case that Northern Ireland would be better off."

But there is real momentum behind devolution of corporation tax - the duty companies pay on their profits - and air passenger duty, Grew says, partly because Northern Ireland competes with lower rates in the Republic of Ireland.

Lord Alderdice, a Lib Dem and former speaker of the Northern Ireland Assembly, highlights "broad agreement" that corporation tax should be devolved. He says Westminster has been "sitting on it" until after the Scottish referendum, when he expects the issue will be revived.

There could be more room on the benches if devolution leads to Parliament downsizing.

4. Fewer MPs?

When the Scottish Parliament opened anew in 1998, it led to a cut in the number of MPs representing Scotland at Westminster from 72 to 59.

Another reduction could potentially take place after further devolution, according to the Scottish Boundary Commission.

The idea that Parliament should get smaller in general is a well-rehearsed one.

The current government brought forward legislation in 2011 meaning the number of seats in Parliament will fall from 650 to 600, but this will not take place until 2018. Of the 50 seats to be abolished, seven would be Scottish.

Prof Trench says using devolution as a basis for reducing the number of MPs is "quite a dangerous idea".

"If you are maintaining a system whereby devolved governments deal with health and education policy and the UK government takes decisions on matters of national importance, it's difficult to see why there should be fewer Scottish MPs voting on, say, whether to go to war, than English MPs."

Where he does see a problem is in Wales, which is currently "significantly over-represented" in Parliament in terms of population.

Others in Wales disagree with that opinion. Dr Rebecca Rumbul of the Welsh Governance Centre describes the English majority in Westminster as "huge".

Some are predicting that Scotland could go the same way as Quebec and hold a second referendum

5. The 'neverendum'

Both sides of the campaign sought to stress that the vote on 18 September was a one-off. Better Together leader Alistair Darling warned "there is no going back" and the Scottish Deputy First Minister Nicola Sturgeon hailed it as "a once in a lifetime opportunity".

But several commentators have drawn comparisons between Scotland and Quebec, where there were two referendums within 15 years as part of repeated efforts to arrive at a constitutional settlement, sometimes referred to as the "neverendum".

A YouGov/Sun poll, external in August found a fairly mixed picture on support for another referendum in Scotland, with 25% backing another vote within the next 10 years and 17% within the next 30 years. Thirty-nine per cent believed there should not be another referendum at all.

Michael Keating, professor of Canadian and Scottish politics at Aberdeen University, doesn't see much appetite for a further referendum.

"A huge amount of time and energy has been expended on this campaign. People will want to get on with the business of renegotiating powers for Scotland."

The legacy of a "No" vote, he predicts, "will not be to kill off the campaign for independence - which will continue - but to put everything on the table in terms of rebuilding the constitution, to fire up debates on welfare, on pensions, on the economy, which were not being had before".

The only thing he does foresee prompting another plebiscite has to do with the possibility of another referendum altogether - on whether the UK should leave the EU.