Today's troops reflect on World War One

- Published

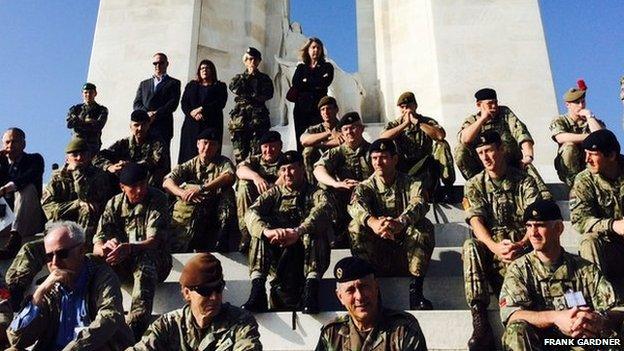

British officers were among those visiting historical sites in September

This year is special for remembrance, for two reasons.

It marks the centenary of the outbreak of World War One, dubbed by that generation as the Great War, a four-year conflict in which over eight million servicemen and women were killed, nearly one million of them from Britain and its empire.

It also marks the end of British combat operations in Afghanistan, a war which technically has lasted for 13 years but which only began in earnest for Britain in the summer of 2006.

The conflict cost the lives of 453 British troops, sent thousands more home with injuries, many life-changing, and became the distant yet defining military conflict of our generation.

So autumn 2014 is an appropriate time for reflection. How can we do more to avoid wars in the future? If we do have to wage them, how can they be fought better, quicker, and with fewer casualties, especially amongst civilians, who so often find themselves caught between opposing sides?

And how best should we honour those men and women who lost their lives in conflicts that have sometimes later come to be seen as ill-judged and poorly executed?

The last UK combat troops left Afghanistan in October

French historians dressed as foot soldiers during visits to battlefields

With WW1 in mind, this September the British Army organised something called a "staff ride", a week-long visit by young officers and their mentors - military historians and retired generals - to some of the most memorable battlefields of 1914-18.

This being the military, it had to be given a name: Operation Reflect. Its aim was "to mark the centenary of WW1 in a dignified, reflective and respectful manner in order to commemorate the sacrifice of our forebears, learn enduring lessons, and educate ourselves and others".

It was a poignant occasion. In warm, late summer sun, with larks singing above fields still dented in places with craters made by the exploding shells of a century past, 161 participants gathered to visit places with names immortalised in history: Ypres, the Somme, Arras and Cambrai.

There were 92 British officers, 40 French, five from Germany and one each from Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Ireland and Belgium. The French military loaned out an entire military base in Lille to the British Army, which arrived with cooks, tents and regimental archives for the Royal Welsh which ran the display.

Understanding conflicts

By Dr Jonathan Boff, military historian

Methods of fighting developed between 1914 and 1918 set the template for warfare ever since.

It's simply impossible to understand the Second World War or even the invasion of Iraq in 2003 without understanding the Great War first.

I joined them at Vimy Ridge, where a memorial to the 11,000-plus missing Canadians soared into the sky and historians, including Professor Sir Hew Strachan, explained how even this slight rise in terrain had huge strategic significance.

Seated on the stone steps, listening, was the new head of the British Army, Gen Sir Nick Carter, a man with enormous recent experience of the war in Afghanistan, and who must now be working out how to apply the lessons of that conflict to future British engagements.

Three times I have embedded with a BBC film crew in his HQs in Afghanistan, both in Kandahar and Kabul, watching as he has grappled with the complexities of Afghan politics while trying to orchestrate military contingents from over 40 countries.

I could not help wondering if the catastrophic waste of life in the trenches of WW1 might have been avoided if troops had been led by frontline generals of that calibre then.

A WW1 tank has been dug up and put on display at Cambrai

At Cambrai, the talk was all about "breaking the stasis of trench warfare." This epic 1917 battle was the first time tanks were used in numbers, aiming to end the paralysis of two static armies dug into the mud of northern France.

Here the officers broke into syndicates to discuss the lessons of that battle, but I reflected how terrifying it would have been for the German troops to face these lumbering metal leviathans that crushed all before them: barbed wire, fences and people.

How horrendous too, it would have been for the crews inside, choking on fumes, lurching with every turn, their bodies crashing against the interior metalwork, deafened by gunfire and bracing themselves for the occasional lucky shell that smashed through the armour and ended their lives.

In a farm near the battlefield, a French man told us how he always believed there was a full-size WW1 Female tank buried in the mud. Eventually he found it, dug it up, with respect he said, as the five-strong British crew had died inside, and he now proudly displays it in a barn.

For us, the day ended at Arras, a market town with cobbled square, where the band of the Coldstream Guards beat the retreat with impeccable timing and choreography, French officers standing stiffly to attention in the warm evening breeze. It was a reminder, as if any were needed in this centenary year, of the sacrifices and horrors of the war that was supposed to end all wars.

- Published9 November 2014

- Published9 November 2014

- Published8 November 2014