GCHQ censured over sharing of internet surveillance data with US

- Published

UK surveillance agency GCHQ has been officially censured, external for not revealing enough about how it shares information with its American counterparts.

The Investigatory Powers Tribunal said GCHQ failed until December 2014 to make clear enough details of how it shared data from mass internet surveillance.

It was the IPT's first ruling against an intelligence agency in its 15-year history.

The Home Office said the government was "committed to transparency".

In December the IPT ruled that the system of UK intelligence collection did not breach the European Convention of Human Rights, following a complaint by campaign groups including Privacy International and Liberty.

But the tribunal has now ruled that the system did "contravene" human rights law - until extra information was made public in December.

In its disclosures in December, GCHQ said UK intelligence services were "permitted" to request information gathered by Prism and Upstream - US surveillance systems which can collect information on "non-US persons".

It said a warrant was usually needed to make such a request, and information would only be sought in "exceptional circumstances" - and this had "not occurred" at the time the statement was made.

Before December, the IPT said: "The regime governing the soliciting, receiving, storing and transmitting by UK authorities of private communications of individuals located in the UK, which have been obtained by US authorities pursuant to Prism and... Upstream, contravened articles 8 or 10 [of the European Convention of Human Rights]."

Article 8 is the right to privacy, article 10 the right to freedom of expression.

The agency is now compliant, the tribunal said.

Analysis

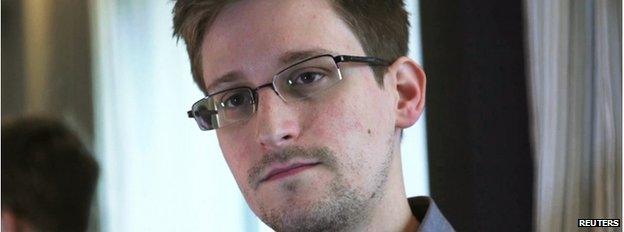

Edward Snowden revealed extensive surveillance by US intelligence

By Clive Coleman, BBC legal affairs correspondent

Since the revelations from Edward Snowden, the former US National Security Agency analyst and whistle-blower, there has been increased concern about the mass collection of personal communications data.

To be in accordance with the law, rules for intercepting data from private communications between people by way emails, phones, etc, have to be clear, accessible and publicly available.

Up until the hearing before the IPT last year, they weren't.

It was only because the security services disclosed documents about their procedures, which had not previously been publicly available, that interception has become lawful.

Some remain unhappy with the regime for the collection of data, but the public now has access to more information about how the security services go about activities which the tribunal has described as "below the waterline".

James Welch, legal director for Liberty, said: "We now know that, by keeping the public in the dark about their secret dealings with the National Security Agency, GCHQ acted unlawfully and violated our rights.

"That their activities are now deemed lawful is thanks only to the degree of disclosure Liberty and the other claimants were able to force from our secrecy-obsessed government."

He said they disagreed with the ruling that GCHQ was now compliant and would fight it in the European Court of Human Rights.

'Historic victory'

Eric King, deputy director of Privacy International, said: "We must not allow agencies to continue justifying mass surveillance programs using secret interpretations of secret laws."

He said the ruling was a "vindication" of the actions of Edward Snowden, the former US intelligence analyst who revealed details about UK and US surveillance practices.

Rachel Logan, of Amnesty International - another of the groups which brought the complaint - said the government had been "rumbled" and the IPT ruling was a "historic victory in the age-old battle for the right to privacy and free expression".

"Governments around the world are becoming increasingly greedy and unscrupulous in the way they sweep up and use our personal information," she said.

"This is about showing that the law exists to keep the government spooks in check."

A Home Office spokesman said: "[The government] has made public more detail than ever before about the work of the security and intelligence agencies, including through the publication of statutory codes of practice.

"We have now made public the detail of the safeguards that underpin requests to overseas governments for support on interception."

A Downing Street spokeswoman said the judgment did not require GCHQ to change its operations.

The IPT is a court which investigates complaints of "unlawful use of covert techniques by public authorities" which breach human rights.

What are Prism and Upstream?

Prism is a mass surveillance system launched in 2007 by the US National Security Agency (NSA).

It allows the organisation to "receive" data held by a range of US internet firms, and was designed to overcome earlier "constraints" in counterterrorism data collection, according to a leaked presentation dated April 2013.

That data apparently includes emails, video clips, photos, voice and video calls, social networking details, and logins.

Companies and internet services it mines include Microsoft, Skype, Google, YouTube, Yahoo, and Facebook, the leaked information suggests.

Upstream is the "collection of communications on fibre cables and infrastructure as data flows past", according to an NSA document.

The implication is that the agency is able to obtain and study communications without having to request the information from internet companies, using its Prism programme.

- Published5 December 2014

- Published17 January 2014

- Published24 June 2014

- Published4 November 2014