Memories of Charles Kennedy from the BBC's John Pienaar

- Published

We've discussed the risks Charles Kennedy took with his health quite often - a tale of a large political figure who marked himself out by his rare and authentic depiction of a normal human being.

Like very many others in my trade, I liked him a lot. And not just because he tried to express undiluted principles and interesting ideas, and to do so in plain English.

You had to like Charles Kennedy because he did his bit to give politics itself a good name - a task probably beyond the powers of any single practitioner of the art, even his.

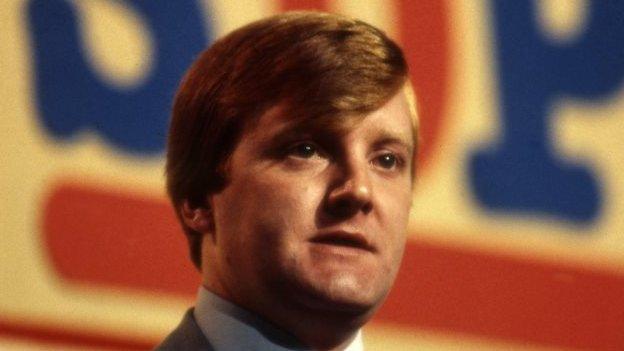

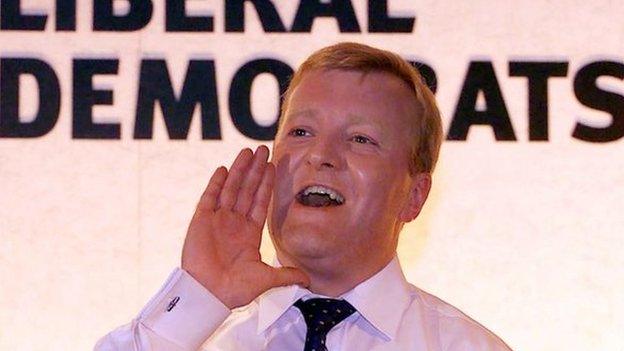

Charles Kennedy in the early 1990s

I remember him very well from his earliest days as the youngest member of the House of Commons, later as party president and then from the early days of his leadership of the Social and Liberal Democrats, as they came to be called.

He started as an MP for the Social Democratic Party - in its day such an exciting and divisive phenomenon, now all but forgotten. As a ludicrously young, new MP at the SDP conference in Buxton he was the centre of any circle he joined.

Charles Kennedy: 1959-2015

By Nick Robinson, BBC political editor

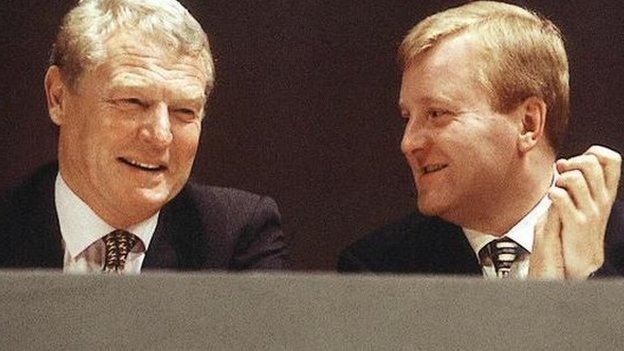

Charles Kennedy left a mark on British politics. The man who took his party to its electoral peak, he was the only UK party leader to warn the country of the perils of invading Iraq when Labour and the Conservatives were uniting to support it.

He was also the only Liberal Democrat MP who could not bring himself to vote to form a coalition with the Conservatives.

But British politics also left its mark on him. Elected at the age of just 23, politics and the House of Commons became his life whilst alcohol was his friend, his prop and his curse.

Charles Kennedy's life in pictures

Shoulder-to-shoulder with vastly more experienced colleagues, bantering with much older, seasoned political hacks and showing a grasp of what no-one then referred to as the "big picture". He made you laugh and he made you listen. And that was why he became leader of his party.

His parliamentary career was extraordinary. He took the party to new levels of strength in the House of Commons, raised their number of MPs twice during two elections. But, if all political careers are a preparation for failure, few leaders end theirs quite so messily.

Charles Kennedy at the Radio 5 live studio in 2001

The rumours of his drinking lagged behind the reality. There were many appearances before the news cameras and radio microphones which fell short, not just of his own enormous capabilities but of the standards his party had every right to expect.

Ultimately his senior colleagues combined in a good old-fashioned plot to depose him. He struggled, hopelessly, but it was no use.

No-one engaged in that plot - and most of them were - did so with anything but deep regret. There was terrible frustration at the leader Kennedy had become. Yet there was almost no personal malice at all.

Charles Kennedy with party leader Nick Clegg during the 2010 election campaign

Just now, and for who knows how long, the Liberal Democrats sit at a very low ebb. Kennedy has left a lasting legacy, though, to his party and to the trade of politics at large.

He showed it is possible to cut through, to engage the attention and affections of a public who rarely spend much time contemplating the humanity of its politicians.

Many tend to categorise our leaders, and those we ourselves elect to represent us as "them". Kennedy, pretty much throughout his time, managed to be seen as one of "us".

He had his weaknesses. Who has not? But his opposition to the war in Iraq - and at the time there was much support as well as hostility to the invasion - was rooted in principle and he articulated the doubts of many.

His almost solitary opposition to the Liberal Democrats decision to combine with the Conservatives in coalition was grounded in conviction as well as a belief the party was, if not cutting its political throat, engaging in a form of self-harm.

Supporters of coalition were principled too. All knew there would be a price to pay in popularity. Yet Kennedy's rather isolated stance arguably demonstrated moral courage and a certain stubbornness.

There is, and must be a place for principle, moral courage and even stubbornness in politics. Mustn't there?

He'll be missed. A lot. And for a long while.

- Published8 May 2015

- Published2 June 2015

- Published2 June 2015

- Published2 June 2015

- Published2 June 2015

- Published2 June 2015

- Published2 June 2015

- Published2 June 2015

- Published2 June 2015

- Published2 June 2015