Paris attacks: Could they happen in the UK?

- Published

Police in London have staged major counter-terrorism exercises to prepare for street attacks

While the UK has sustained far, far fewer casualties from jihadist violence than France, all of the available evidence indicates that the terrible events inflicted upon Paris could happen here - and security chiefs have long planned for that possibility.

The statistical chances of being caught up in a terrorist incident are pretty low - but the official government position is that there is a "severe" threat from international terrorism.

That means security chiefs think an attack is highly likely - just one notch down from "critical", the level reached in the extreme situation of an attack being imminent.

How do security chiefs reach this conclusion? Cold, hard analysis of the intelligence picture at home and abroad - events that we see in public, such as arrests that lead to criminal convictions, and intelligence operations in the shadows that we never hear about.

How serious is the terrorism threat in the UK?

Official threat level is "severe" - meaning an attack is thought highly likely

Scotland Yard says there have been "six attempts to carry out an attack" over the last 12 months.

Approximately 600 separate counter-terrorism operations across the country

Arrests are running at an average of one a day

Every event is considered for whether it can provide a clue to the threat faced by the UK. The deaths in France, the downing of the Russian jet over Sinai, the tourism attacks in Tunisia and the dozens killed in suicide bombings in Beirut on the same day as the Paris atrocities, are fed into this analysis which is conducted by Whitehall's Joint Terrorism Analysis Centre.

British security planners have progressively widened their focus as the threat landscape has changed.

Al-Qaeda style mass-casualty bomb attacks - once the primary international threat - are hard to organise because they take manpower, technical know-how and a long time to prepare.

The harder something is to organise, the more opportunities there will be for security services to spot it.

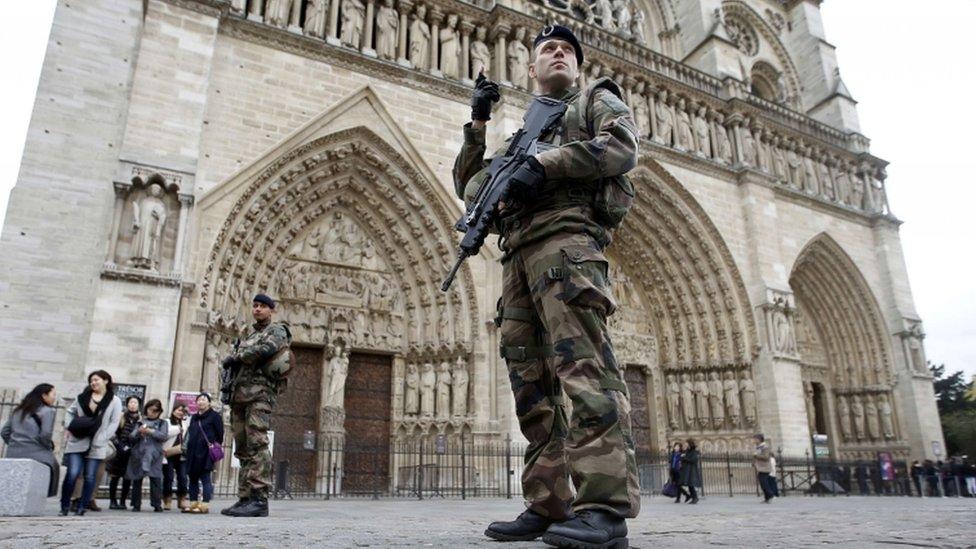

Armed guards: France authorities have deployed soldiers around Paris

A marauding attack on the streets is, in contrast, far more random and, at its worst, completely unpredictable if the individuals never featured on a security radar.

What will concern many security planners greatly about the Paris attacks is that the assailants combined an element of substantial planning - large public targets, substantial weaponry and a suicidal endgame - with the unpredictability of a marauding assault.

At the same time, many security chiefs will not be surprised at all because the signs have long been apparent that this kind of attack was possible.

The self-styled Islamic State is now the leading jihadist group thanks to its unparalleled territorial gains, resources, manpower, funding and, critically, multi-lingual online media operation. It projects a vision that it is "winning" (despite severe setbacks like the loss of entire towns ) that have augmented its "brand power" among would-be recruits. Most importantly, in September 2014, its leading public ideologue called on followers overseas to launch attacks without waiting for permission or specific direction.

This call to action - IS styles it a "fatwa", or religious ruling, so they can convince followers of their divine righteousness - had a profound and immediate effect. It can be directly linked to a series of attacks in Canada, Belgium, Australia, Denmark and, of course, France.

So, it's now clear that gun attacks - marauding or focused - in Europe are an enduring security challenge rather than just a random one-off event.

UK reaction to Paris attacks: Live coverage

So here's the question - how prepared is the UK?

Earlier this year, parts of London were sealed off for a major Metropolitan Police exercise called Operation Strong Tower.

The two-day role-play event involved counter-terrorism officers, MI5, the military and emergency services hunting down a jihadist cell shooting and bombing its way across the capital.

In short - it was an attempt to "stress-test" how they would all respond to exactly what has happened in Paris. Fairly obviously, the results are secret - but that kind of live training has been complemented with physical and organisational changes to the city.

Many of London's buildings are surrounded by bollards designed to withstand lorry bombs. CCTV and number plate cameras are everywhere. Specialist armed police - trained to a military standard - carry out daily patrols designed to strategically cover as much of the capital as possible.

Watching: UK cities are covered with vastly more CCTV cameras than those in France

One major difference with continental Europe is guns. The availability of firearms in the UK is very low compared with other countries because of the country's strict gun-control laws. It is hard to smuggle them in - although not impossible - and operations to disrupt organised criminals from doing so rely on both the UK's border controls and secret intelligence techniques.

Only two weeks ago, on the publication of the government's proposed plan to expand investigatory powers, did we learn that MI5 and GCHQ have been running "bulk" sifts of communications flowing across the internet as they search for potential threats.

Were Paris-style attacks to happen in the UK, the police and security agencies would immediately want to launch a major analysis of communications data to identify the network around the perpetrators. So supporters of the draft Investigatory Powers Bill, external will urge its opponents to think about Paris.

How would a city like London respond? In theory, better than in the wake of 7/7.

During the inquests into the 2005 bombings, there was evidence that the emergency services were both overwhelmed and, at times, incapable of communicating properly.

All of that has now supposedly changed - underground stations and tunnels, for instance, are now all categorised and numbered with agreed meeting points for first-responders. Across the rest of the UK there are specialist response teams involving all of the emergency services.

And dotted across the capital in secure locations are special emergency trauma kits - which mean that police who rush to a scene of an attack may have a greater chance of saving lives.

Would they save lives? The evidence suggests they would - but then the devastation of Paris shows how difficult that job ultimately would be.

- Published14 November 2015

- Published30 June 2015