How likely am I to become an astronaut?

- Published

"I want to be an astronaut." It's an ambition held by many - perhaps even most - children at one stage, but what really are their chances?

Briton Tim Peake's landmark trip into space will no doubt have lit a fire in the minds of many youngsters, eager to pursue a similar dream.

Tim Peake was one of six astronauts chosen by the European Space Agency (Esa) in its last recruitment round, external - 8,413 qualified for the selection process.

In the last Nasa recruitment, eight people were chosen out of 6,100 applicants.

It's not sounding good for little Jane or Johnny so far... but don't lose heart.

Dr Marek Kukula, public astronomer at the Royal Observatory Greenwich,, external is optimistic.

"I think over the next few decades the opportunities to go will become greater, both as part of official government missions, but also as space tourism becomes more common.

"It'll be something that more and more people can aspire to."

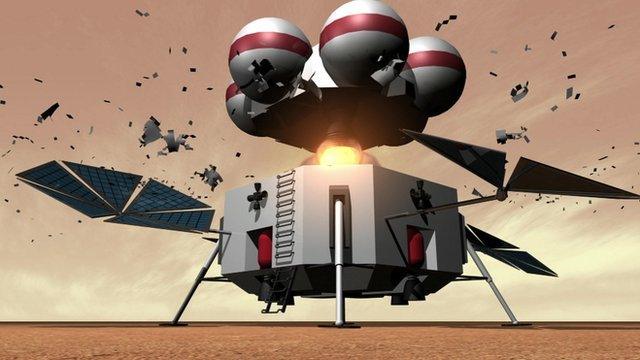

He adds: "Mars is the big dream. We're talking 30 years for that, but some of the children watching Tim Peake's launch will be the ones who get to land there. "

Do you have what it takes to be an astronaut?

So how do you become an astronaut? Well, there's no milk round, no graduate scheme and no foot-in-the-door because daddy works for Nasa.

Esa isn't currently recruiting - indeed it's only ever held three recruitment rounds - in 1978, 1992 and 2008.

Nasa, though, recruits every few years, and it's actually hiring now, external. Japan and Canada also train astronauts, while Russia only had 151 applications for its last round of vacancies, so your odds could be better there.

But remember that in all those cases you need to be - or become - a citizen of the particular nation to apply to its space programme.

First off, you'll need a degree - and most likely a PhD - in biological, physical, chemical or computer science, engineering, or maths - and at least three years' job experience.

Another option is to become a fast jet pilot and once you've logged at least 1,000 hours of flying you can apply for the next job up - almost literally.

A second language would definitely be useful - Russian is the top of the list for the Esa - and as with most sought-after jobs, the more strings to your bow the better.

Among those chosen by Nasa in 2013,, external there was an assistant professor of anaesthetics at Harvard, a station chief for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and a US military expert on improvised explosive devices.

"Astronauts are quite remarkable generalists who can be assigned to a broad range of activities and who really have the ability to adapt to that," says Frank Dansey, head of human resources at the European Space Operations Centre.

"We don't hire astronauts all the time. But what I can say is that of those who became astronauts they prepared perpetually, as though the next campaign was just around the corner."

One bit of good news is that there are no age restrictions at Nasa or Esa - candidates have ranged from 26 to 46 - but you have to be in good shape to handle what zero gravity does to the body.

Nasa candidates have to pass the military's water survival course, external and show they can cope with high and low pressure environments. Their vision must be 20/20 - or correctable to that acuity - and blood pressure a maximum of 140/90.

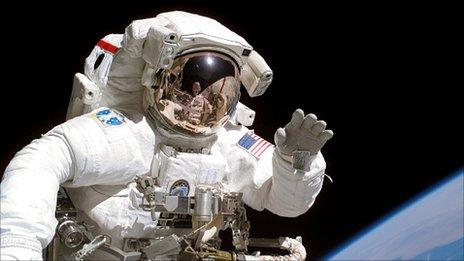

No room for arguing: Tim Peake is heading for six months on the International Space Station

Rigorous psychological tests are also a key part of the selection process.

It can be dangerous, you're away from home for a long time and you're trapped in very close quarters with a few other people. Candidates need to show they can take the strain and be a team player.

Increasingly, an astronaut's job also involves public outreach and education, so you need to be a good communicator. And if you can hold a tune like Chris Hadfield, that's even better.

Finally, you could still fail to make the grade when it comes to the actual technical training required.

It takes 40 months to learn everything Esa demands: how to operate the rocket and space station, and how to fix things if they go wrong; how to walk in space and how to perform the scientific experiments you've been sent to do.

Not just pilots

"To be an astronaut takes a lot of hard work. You have to have all sorts of skills, but quite a lot of people are capable of that - it's just a question of putting in the work," Dr Kukula says.

"Ask people like Helen Sharman and Tim Peake. I bet when they were kids they probably thought, 'impossible dream', but they managed to do it.

"And as we try to do more things in space, we'll need to people with a wider range of abilities.

"At the moment, astronauts tend to come from quite unusual backgrounds - fighter pilots, for example - but even on the moon missions 50 years ago, there were scientists on board, people with other skills."

Space recruits of the future could well spend less time floating around and more time on solid ground.

"The space agencies have plans for a permanent base on the moon, for example, where people can live for months at a time," Dr Kukula explains.

"There's even talk of hotels, so that'll require a much wider range of people."

A giant leap onto the red planet is the prize for the next generation of space explorers

That all sounds encouraging for the next generation, but even if you can become an astronaut, should you? Are there better ways to advance the course of human knowledge?

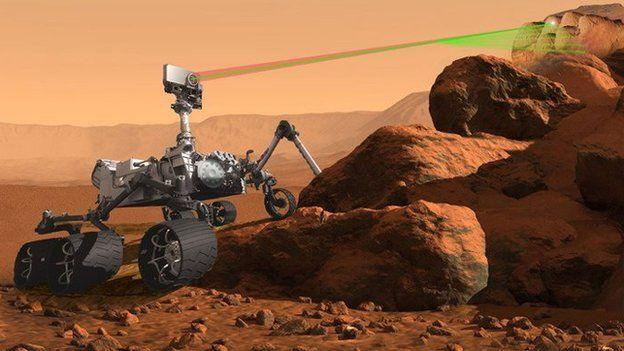

Prof Andrew Coates, from University College London's Mullard Space Science Lab,, external is working on the unmanned ExoMars mission which is aiming to send a European rover and a Russian surface platform to the surface of the red planet in 2018.

"For me, the best use of manned missions is as inspiration, and if all this attention and excitement around Tim Peake inspires even a handful of young people then it's worth it," he says.

"But that's not cutting-edge science or exploration. Unmanned missions, robotics, that's where the real boundaries are being pushed."

So what could today's child be doing in 20 years or so?

Working on a mission to Jupiter. Mapping the Milky Way. Trying to land on an asteroid. Looking for signs of life on Mars.

And all, Prof Coates says, without leaving Earth: "Not everybody can be an astronaut but a lot of people can get involved in studying space and science.

"The UK space industry is really growing and it's going to need a lot of good people."

- Published16 October 2015

- Published14 November 2013

- Published24 July 2013

- Published7 April 2011