How Islamic State group supporters targeted the UK

- Published

Junead and his uncle, Shazib Khan were also found guilty of planning to go and fight in Syria

A delivery driver from Luton has been found guilty of plotting a terror attack on US military personnel in the UK as a show of his allegiance to the self-styled Islamic State group. What does his case say about the nature of the threat faced by the UK?

Three months. Three juries. And each has found beyond reasonable doubt evidence of attack planning in the UK linked to the self-styled Islamic State fighting group.

The three cases that have seen convictions are part of the seven IS-linked plots referred to by the prime minister, external - although never officially detailed - that he says prove the group's threat to the UK.

Just before Christmas, Nadir Syed was found guilty of planning an attack in London timed for around Remembrance Day 2014.

Separately, two London students are facing life sentences for organising what would have been a "drive-by" shooting in the capital.

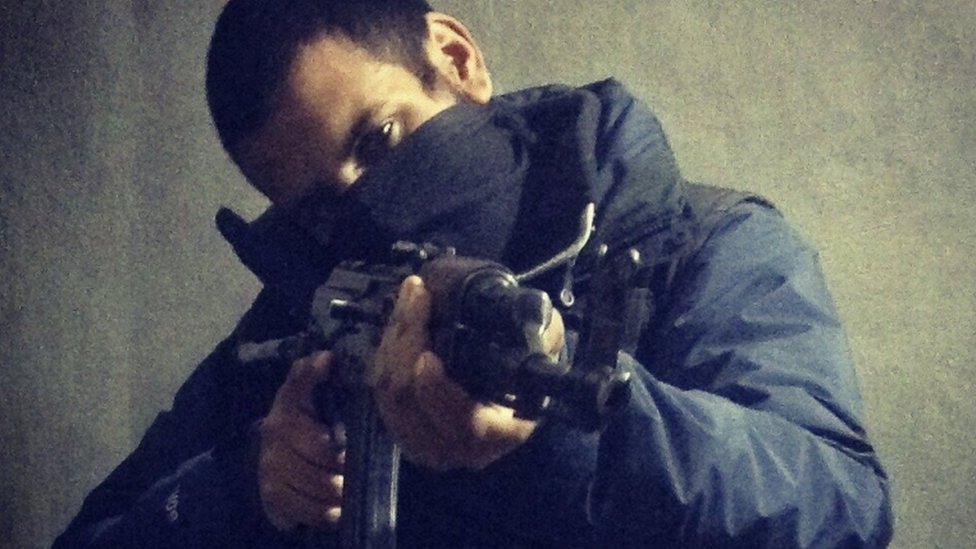

The third man heading to jail is Junead Khan, a pharmaceutical company delivery driver from Luton.

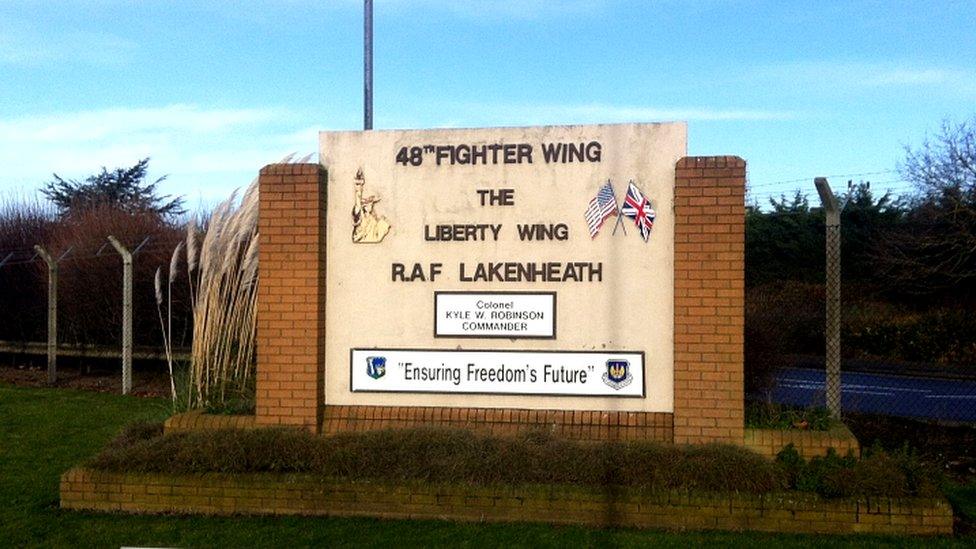

His trial heard he wanted to emulate the killers of Fusilier Lee Rigby in Woolwich in 2013. He planned to run over a member of the US military outside RAF Lakenheath or RAF Mildenhall in Suffolk - the two massive bases used by the US Air Force.

Having done so, prosecutors said he would have tried to draw in security forces, before detonating a homemade bomb in a pressure cooker.

Junead Khan passed the US air bases during his delivery rounds

Junead was accused alongside his uncle, Shazib Khan (who, confusingly, is younger than him) of planning to go to fight in Syria.

The jury found Shazib guilty of preparing to travel to Syria to join IS.

Junead Khan was also found guilty of preparing to travel to Syria, as well as the more serious charge of preparing to carry out a terror attack on US military personnel in Britain.

His conviction is the first where there has been evidence in open court that the suspect was in direct contact with a British IS fighter who was assisting the plans.

Junead Khan was born in the UK and spent some of his childhood being educated in Bangladesh. He left school with few qualifications and tried various jobs before becoming a delivery driver.

Junead Khan told the trial he rejected democracy, and shared this doctored image of Downing Street

The trial heard that the Khans, who regarded themselves as cousins, had been visited by officers tasked with persuading potential extremists to change course.

"In early 2014 local prevent engagement officers had contact with Junead Khan," said Commander Dean Haydon, the head of counter-terrorism at Scotland Yard.

"There were numerous contacts over a period of time. We tried to engage him into the Prevent program which is all about trying to move people away from radicalisation and extremism.

"But he refused to engage and as a result of that what we then saw is an escalation in his extremist activities."

By June 2014, and the declaration of the so-called Islamic State, Junead Khan was actively considering travelling because he was excited by the prospects of a land run along genuinely Islamic lines.

By his own admission he had rejected democracy in favour of sharia law and spent the last general election vandalising candidate posters and urging people not to vote.

Why he didn't go is unclear. Junead told the trial he decided it would be too difficult. But another man from Luton had made it.

Luton man Aziz with another British recruit, Abu Rumaysah

That man was Abu Rahin Aziz, who had previously skipped bail while under investigation and he made it to the warzone.

On 5 July 2015, it emerged that Aziz had been killed in an US drone strike.

That same evening, Junead Khan was in contact with another British fighter, Junaid Hussain, via an encrypted app. And they talked about targeting American military personnel.

Hussain, a computer hacker convicted of accessing Tony Blair's address book, had fled to Syria and reportedly married Sally-Anne Jones, one of the most high profile IS-supporting British women, in the war zone.

"I can get [you] addresses but of British soldiers," Hussain told Khan.

Junaid Hussain: Hacker who fled to Syria

"But more soldiers live in bases which are protected. I suppose on the road is the best idea or… if you want akhi [brother] I can tell u how to make a bomb."

Junead's reply indicated that he been considering such a plan during his delivery rounds near the Suffolk air bases.

"When I saw these US soldiers on road it just looked simple," he said. "But I had nothing on me or would've got into an accident with them and made them get out the car."

Hussain replied: "I have a manual for pressure cooker bomb… It's best to have at least pipe bombs or pressure cooker bomb in a backpack in case something happens. So u can do isthishadi [suicide] bomb in case they try arrest u."

Arrest

Junead Khan received the plans. He had already researched buying a combat knife. Now all he needed was the wherewithal to build the bomb and an appropriate moment to strike,

Colonel Steve Warren, a spokesman for the US military, told the BBC that while Junaid Hussain was thousands of miles away from the UK, he had proven himself to be every bit as dangerous.

"Unlike a single fighter with an AK-47 on the ground in Syria he had the potential through his cyber efforts to reach across the sea and to motivate, radicalise and inspire violence in foreign countries around the world," he said.

The plot never went any further. Junead Khan had been under surveillance since 30 June 2015 and on 14 July undercover police, posing as company managers, asked to see his driving records on his smart phone.

In doing so, they were able to secure evidence of his secret chats before the phone could be permanently encrypted or wiped.

When officers then tried to arrest Junead, he resisted and had to be pinned down for handcuffing.

"You liars, you liars, you have no evidence," he shouted. "Is death never going to find you? You think you are powerful. May Allah destroy you."

Days later, Hussain was back online looking for others to work with. He urged potential recruits that it was their duty to get in touch and find out how to detonate a bomb in the land of the "crusaders".

And then, with the help of another hacker, he is believed to have obtained the personal details of more than 1,000 US government employees.

Hussain tweeted the link declaring: "We are in your emails and computer systems, watching and recording your every move."

On 25 August he was killed in an US drone strike.

- Published27 August 2015

- Published18 June 2014