Hillsborough and the long journey to change the police

- Published

Hillsborough families after this week's inquest verdict

There is a very important legal maxim: justice delayed is justice denied. Never was that truer than in the battle for answers over Hillsborough.

A 27-year wait to hear a jury say that the police were wrong, that the fans were innocent and 96 blameless people had been unlawfully killed.

Whatever comes next with the criminal investigations and the allegations of cover-up, the conclusion of the Hillsborough inquests is a watershed moment for holding British police to account.

Hillsborough inquests: What you need to know

Five Hillsborough myths dispelled by inquests jury

Hillsborough inquests: The 96 who died

The story of how power has shifted away from the police and the development of laws and rights that make them accountable to the people is so long that you can, arguably, start the journey in Manchester on 16 August 1819.

That was the date of the infamous Peterloo Massacre. Soldiers were sent on to the streets and cut down people demanding the vote. They were not put on trial or accused of incompetence. Despite national outrage, they were congratulated by the government of the day.

Peterloo Massacre: No officers in the criminal dock

Within a decade Sir Robert Peel had come up with his famous model of unarmed community policing that would eventually see the end of soldiers on the streets.

But while the Bobbies were welcomed, powers to challenge their authority (assuming people were brave enough to try) were basically non-existent - and history shows how unchecked power can lead to creeping abuse.

The 1970s saw a series of massive miscarriages of justice in relation to the IRA's bombing campaign: the Guildford Four and Judith Ward in 1974, the Birmingham Six in 1975 and the Maguire Seven the following year. It took two decades to right those wrongful convictions.

There were two failed prosecutions of police officers in relation to Guildford and Birmingham - but also a Royal Commission on criminal justice that led to a fundamental separation of powers.

For years the home secretary, the minister in charge of the police, had held the final say on which claimed miscarriages of justice were reviewed.

That ended in 1995 when Parliament created the independent Criminal Cases Review Commission to perform those public duties.

While all of this was going on, the police themselves were being forced to modernise their practices.

Brixton riots: Led to new rights for suspects

The 1981 Brixton riots, triggered after years of pent up anger about allegations of racist policing, ultimately prompted the 1984 Police and Criminal Evidence Act.

The legislation defined the legal limits on powers of arrest and search, how officers should treat suspects. Out went interview room thuggery - in came tape recordings and later cameras.

The riots also had a huge influence on the development of "neighbourhood policing" - a modern day attempt to recapture Peel's vision of police who were part of the people, not distant, disconnected and suspicious of the communities they patrol.

Time and again, the balance has continued to move. Not fast enough for many - but move it has.

Two inquiries that have changed policing

Scarman 1981: The report into the Brixton riots said "complex political, social and economic factors" triggered the violence. Black communities had lost confidence in an overwhelmingly white police force. Scarman said there was racial discrimination and "disadvantage", particularly around the misuse of stop and search.

Macpherson inquiry, 1999: The Stephen Lawrence murder inquiry went further than Scarman, calling the Metropolitan Police "institutionally racist". Macpherson called for the government to strengthen inspection of forces and account for how they deal with racist incidents.

When the 1999 Macpherson report, external into the murder of Stephen Lawrence damned the Metropolitan Police as institutionally racist, it was a moment as powerful as Hillsborough was this week: a public recognition that the police can be catastrophically wrong.

In the wake of Macpherson, Parliament created a groundbreaking race equality duty - a legal means of forcing public bodies, like the police, to protect people from racism. Today that has been expanded into a wider duty that demands that all must be served equally.

Where does all this and many other incremental steps leave British policing? Do the forces now serve the public the way they are supposed to - the way the Hillsborough jury said they should have been serving them all along?

The short and simplistic answer to that question is that there are now a remarkable range of laws, practices and bodies in place that are designed to do just that.

There is a beefed-up police watchdog (soon to be beefed up again), a tough-talking inspectorate of constabularies and elected commissioners who can boot out chief constables who don't command the public's support.

Recruitment and training has changed - it's hard to get on and up in the modern police without a decent degree. The increasingly important College of Policing is responsible for setting the standards - including a code of ethics.

Human Rights Act

And then there is the 1998 Human Rights Act which brought the European Convention on Human Rights into British law. It alone had an enormous role in the battle for answers over Hillsborough.

Article Two of the Convention is the Right to Life and the courts say that means the state must properly explain what happened if the police or another agency have a role in someone's death. Without Article Two, the Hillsborough families may have still been waiting for answers.

European Convention on Human Rights: Article Two

1. Everyone's right to life shall be protected by law. No one shall be deprived of his life intentionally save in the execution of a sentence of a court following his conviction of a crime for which this penalty is provided by law.

2. Deprivation of life shall not be regarded as inflicted in contravention of this Article when it results from the use of force which is no more than absolutely necessary:

(a) in defence of any person from unlawful violence;

(b) in order to effect a lawful arrest or to prevent the escape of a person lawfully detained;

(c) in action lawfully taken for the purpose of quelling a riot or insurrection.

But that's not the whole story. For critics, it is a terribly naive and rosy view of the world. The Plebgate affair - where a police officer ended up in jail after lying to bring down a cabinet minister - is an example of how someone corrupted by power thinks they can get away with it. There are many ongoing campaigns about deaths in custody. And, more generally, a sense among those critics that when times are tough they will still close ranks.

That abiding suspicion has led to a campaign for a "Public Advocate", external who would be appointed to represent the interests of bereaved families in major disasters - someone who would have full access to confidential or secret documents, without needing to go begging to the police or Home Office.

Other than Hillsborough, there are at least three major tests ahead of how much the public can learn about the police and whether alleged wrongdoing can be exposed and stopped from happening again.

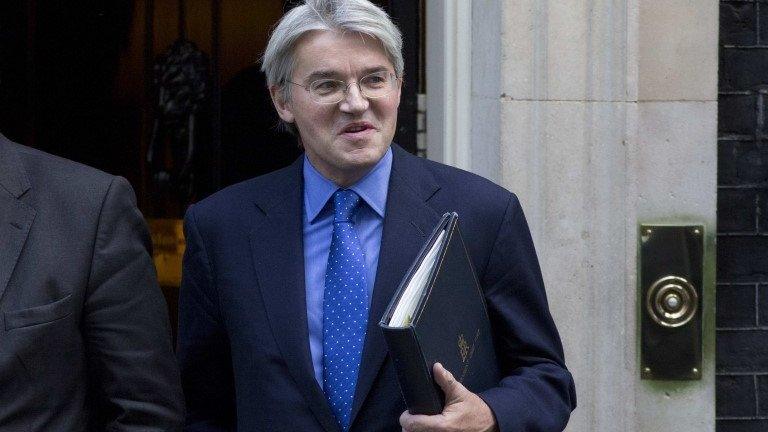

Andrew Mitchell MP stood down as government Chief Whip over the Plebgate affair

We're still to learn if the long-promised "Leveson Part Two" inquiry, external into the extent of unlawful or corrupt conduct and relations between the press and police will ever happen.

The separate and mammoth historical child abuse inquiry will take years to find answers: will it find that some police officers covered up for paedophiles in positions of power?

And the undercover inquiry, perhaps the most complex of all, could decide in the coming week the extent to which it will agree to hold hearings behind closed doors.

- Published10 August 2015