Liz Truss urged to 'get a grip' over inmates kept in jail beyond their sentence

- Published

- comments

Justice Secretary Liz Truss must "get a grip" on the backlog of inmates being held beyond their sentence, the chief inspector of prisons has said.

Peter Clarke said it was "completely unjust" that offenders serving Imprisonment for Public Protection (IPP) terms were "languishing in jail".

He warned that IPP sentences, abolished in 2012, were having a serious effect on prisoners' mental health.

The Ministry of Justice said a new unit had been set up to tackle the problem.

More than 3,800 prisoners in England and Wales are serving indeterminate IPP sentences, designed to protect the public.

Of those, 500 should be let go, former Justice Secretary Michael Gove said, when he delivered the annual Longford lecture in memory of prison reformer Lord Longford.

Mr Gove said executive clemency should be granted to release prisoners who had served far longer than the tariff for their offence and had now - after multiple parole reviews - served even longer than the maximum determinate sentence for that offence.

Speaking to the BBC's Today programme, Mr Clarke said Mr Gove was the latest in a line of secretaries of state who had pointed out flaws in the system.

The prisons inspectorate identified problems with IPP sentences eight years ago, yet little had been done since and progress was "painfully slow", Mr Clarke said.

He added: "This should be addressed as a matter of urgency, and it's not just a case of resources - there have been failings and blockages in the prison service, in the probation service and the parole board.

"And we suggest that the only person who's got the authority to get a grip on the way things happen - it may mean policy changes...is the secretary of state [Liz Truss]."

Mr Clarke is a former assistant commissioner with the Met Police

On prison visits, he said inmates - including one who was seven-and-a-half years over his tariff - told him they felt "trapped in the system" and unable to prove that they were no longer a risk to the public.

One IPP prisoner, James Ward, told the BBC he feared he would never get out. He is in his 11th year in prison after being given a 10-month sentence for arson.

What were IPPs?

Introduced in 2005, the sentences were designed for high-risk criminals responsible for serious violent or sexual offences.

If, at the end of their tariff, their danger had not been reduced sufficiently, they would continue to be detained until they had satisfied the Parole Board that they could be managed safely in the community.

But the punishments were abolished in 2012 after it emerged they were being used far more widely than intended - and in some instances for low-level crimes.

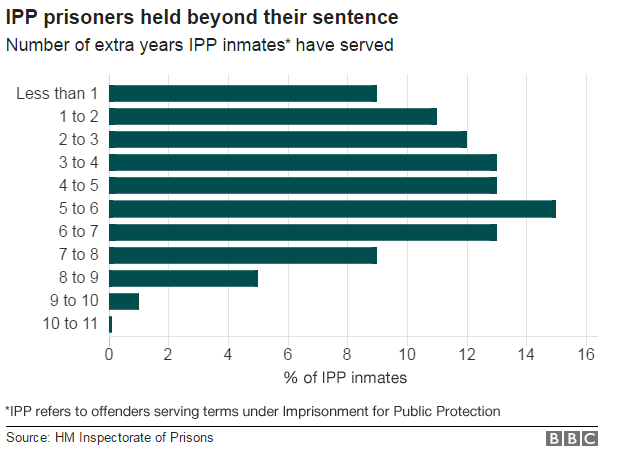

Some 3,200 prisoners have served more than the tariff or minimum sentence they were given, while 400 of them have served at least five times the minimum.

Mr Clarke was speaking as HM Inspectorate of Prisons released its report saying "significant failings" in the prison, probation and parole systems were contributing to the numbers still in custody years after the end of their tariff.

They have been denied the opportunity to demonstrate whether they present a continuing risk to the public, or to have this properly assessed, the study added.

Peter Clarke tells Radio 4's Today prisoners are denied the chance to prove they're not a risk.

Mr Clarke said it was widely accepted that the implementation of the sentence was "flawed".

He said that while some on IPP sentences remained dangerous, others presented a much lower risk to the public but "system failures have impeded their progress".

"The problems with the legacy of the IPP sentence are well understood and there is an openness in government to find new and innovative solutions to the problem," he said

'It's madness'

"I wake up every morning scared of what the day may hold," says James Ward

James Ward was given a 10-month IPP for arson in 2006. Now in his 11th year in prison, he still has no release date.

He regularly self-harms, sets light to his cell, barricades himself in and has staged dirty protests.

With a low IQ, and mental health problems, he cannot cope with prison life.

In a letter he wrote to the BBC last week, he said he was struggling inside prison.

''I'm hoping they let me out with some support because I'm not getting none in here.

"Hopefully it will happen but I doubt it."

He has a parole board hearing in January, when his solicitor will be arguing for his release.

His sister, April Ward, says he has recently cut his wrist.

"We always worry about James," she said. "The biggest fear for my mum and dad is that they will never see James walk free and live a normal, happy life."

She said his prison had given him the job of cleaning out prisoners' cells, which meant wiping blood off the walls where other prisoners had self-harmed.

Prisoners asked him to pass drugs between the cells and when he refused, they threw things at him.

"He feels like he's been forgotten about, that nobody wants to help him. Nobody wants to take responsibility for the IPP sentence. It's madness," she added.

In July, the Parole Board chairman Nick Hardwick said Ms Truss "needed to consider" changing the release test to make it easier for IPP prisoners to be freed.

In Wednesday's lecture, Mr Gove called Mr Hardwick "superb" and said he should be given the resources and flexibility to ensure more IPP cases could be processed and more individuals released.

A Ministry of Justice spokesman said: "Public protection remains our key priority, however this report rightly highlights concerns around the management of IPP prisoners.

"That is why we have set up a new unit within the Ministry of Justice to tackle the backlog and are working with the Parole Board to improve the efficiency of the process."

- Published23 June 2016

- Published30 May 2016

- Published18 March 2016