Secure exit? How will Brexit affect UK security?

- Published

Will Britons be safer, more at risk, or see their security largely unchanged once the UK exits from the European Union?

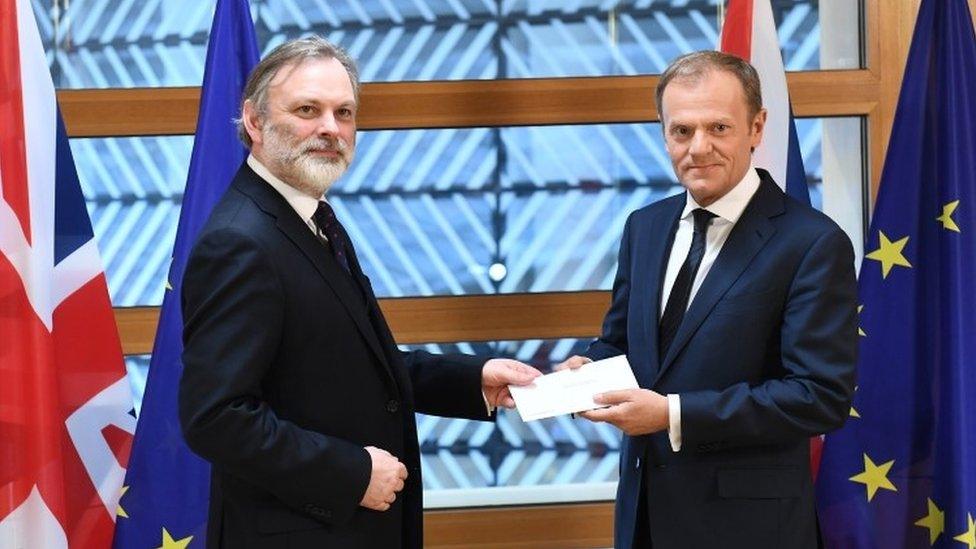

In the historic letter triggering Article 50 published on Wednesday, the Prime Minister Theresa May warned that failure to negotiate an agreement could damage security cooperation and the fight against crime and terrorism.

The arguments over the security implications for the UK that circulated at the time of the June 2016 referendum are now being revived, but with rather more substance.

The most serious and the most immediate security threat is that of a major terrorist attack, perhaps one even worse than the one in Westminster on 22 March.

In police jargon, the nightmare scenario they have been rehearsing for years for is known as a "Marauding Terrorist Firearms Attack" (MTFA) - using machine guns to kill pedestrians in a crowded public place.

Given this is still an objective for the so-called Islamic State - coupled with the presence of large numbers of jihadists across Europe, especially those returning from Syria and Iraq, and the proliferation of automatic weapons available in the criminal black market on the Continent - close cooperation between the UK and its European partners will continue to be key to stopping terrorist attacks in time.

Intelligence officers from MI5, senior policemen and women from the Metropolitan Police Counter Terrorism Command, the prime minister's national security adviser and the National Security Secretariat have all been studying what effect, if any, Britain's departure will have on our security. So what are the arguments for and against?

Less secure?

In the Brexit-triggering letter, the prime minister set out her fears of what could happen if the next two years of negotiations ended in failure and Britain exited the EU without a deal.

"In security terms, a failure to reach agreement would mean our cooperation in the fight against crime and terrorism would be weakened. We must therefore work hard to avoid that outcome."

A recent study by the Rand Corporation concluded that "both sides [the UK and EU] risk becoming weaker and less secure if Brexit talks provoke a 'zero-sum' approach to security and a 'messy divorce'".

Europol's Rob Wainwright is concerned at the impact of Brexit on the fight against crime

The director general of Europol, the pan-EU police force headquartered in The Hague, has expressed grave concerns that Britain's departure will adversely affect the fight against organised crime, international terrorism and cybercrime.

Rob Wainwright told the BBC: "To help keep Britain safe from these threats, its law enforcement community has become dependent on the unique operational benefits offered by key EU instruments: over 3,000 cross-border investigations of organised crime and terrorism were initiated last year at Europol by UK agencies, a rate 25% up on the year before."

There is, however, a subtle distinction between fighting "ordinary" crime and countering terrorism (CT).

In fighting crime, the UK has benefited from both membership of the European Arrest Warrant and Europol.

But counter-terrorism officials admit privately that neither are indispensable when it comes to sharing intelligence on terror suspects.

This is often gathered by highly secretive intelligence agencies who are unwilling to share sensitive material, in real-time, with Europol.

One pan-European mechanism Britain's CT community does value highly is the Second Generation Schengen Information System (SIS II).

This provides a framework for the timely exchange of information on suspects believed to be at large in Europe, and at risk of slipping unnoticed across borders, something the 2015 Paris attack planners managed to do with ease.

But shutting Britain out of this club would be counter-productive for the rest of Europe, so officers are confident it will be retained after Brexit.

Scotland is another worry.

A Trident submarine makes its way out from Faslane naval base in Scotland

If Brexit does result in Scotland voting for independence from London, then there will inevitably be huge implications for UK defence and security.

The UK's Trident submarines, known as the "continuous at sea deterrent", are currently based in Scotland and would quite possibly have to be moved south of the border.

Theresa May wrote in her letter that attention needed to be paid to "the UK's unique relationship with the Republic of Ireland and the importance of the peace process in Northern Ireland".

The border between north and south, which is currently open, would almost certainly be tightened.

Ms May reminded everyone that the Republic of Ireland was the only EU member state with a land border with the UK, and that her government did not want a return to "a hard border" between the two countries.

She also said nothing should be done to jeopardise the peace process in Northern Ireland.

Then there is Russia. MI5's efforts to thwart espionage by Russian agents will continue post-Brexit, as will GCHQ's efforts to prevent cyber-espionage and hacking.

But on the diplomatic front, there is no question that the EU's united stand towards Moscow on sanctions, Crimea and eastern Ukraine will be weakened by the departure of one of the strongest and most outspoken governments.

It should be remembered though, that Nato is responsible for the military defence of Europe, not the EU, and Britain is not leaving Nato.

Safer off?

One of the most emotive and persuasive arguments put forward by supporters of Brexit was that leaving the European Union would allow the UK to regain control of its borders, giving it back control over who it lets into the country.

In the long term, the indications are there is some truth in this where EU citizens are concerned. But the mechanics are still being worked out and there are numerous exceptions and loopholes.

It also ignores the fact there are an estimated 3,000 British citizens - at the minimum - whom the government is aware of having jihadist connections, contacts and sympathies.

The detailed effect of Brexit on the UK's borders is as yet unknown

These are people who are already living here and who in most cases have been radicalised over the internet or by their peer group without even travelling to a battlefield like Syria.

No change?

One person who has been right at the cutting edge of counter-terrorism for five years is Richard Walton.

He was Commander of the Met Police's SO15 Counter Terrorism Command from 2011-16, and he has firm views on this issue. "The UK could leave both the EU and Europol with little, if any, impact on its own national security or counter-terrorism capabilities," he wrote recently.

Based on his own frontline experience, he believes that Britain's unique expertise in this area is much too valuable for EU countries not to keep lines open and two-way information flowing.

This is partly due to the close cooperation enjoyed between the police and MI5, which evolved in the wake of the 2005 London bombings, a relationship which is not mirrored in most other EU countries. (Belgium, for example, has a long way to go to improve cooperation between its various agencies).

Not surprisingly perhaps, Europol's Rob Wainwright disagrees with Mr Walton. He maintains that Europol, of which the UK is currently a member, is fast becoming indispensable.

"Recent Europol reforms and improved levels of trust in it by national agencies," he explained to the BBC, "have witnessed a ten-fold increase in the sharing of terrorism data with Europol in the last two years (across Europe as a whole)."

The home secretary says threats to the UK's security have not been changed by the Brexit vote

But Mr Walton also argues that Britain's membership of the 5 Eyes intelligence sharing agreement gives it a special place in Europe.

5 Eyes is an extraordinarily close and trusting arrangement between the intelligence agencies of the US, Canada, UK, Australia and New Zealand. As the only European nation in this "club", Britain's membership will endure beyond Brexit, while EU governments will want to continue to have access to any intelligence that affects them.

In December 2016, six months after the referendum, the Home Secretary Amber Rudd was quoted as saying: "The threats and challenges to UK national security have not fundamentally changed as a result of the decision to leave."

This week, in the wake of the attack that killed four people in Westminster on 22 March, Richard Walton commented: "Brexit will make no difference to Westminster or any subsequent counter-terror operation, proactive or reactive."

Essentially, he says, it remains business as usual.

- Published30 March 2017

- Published29 March 2017

- Published29 March 2017

- Published29 March 2017

- Published23 March 2017

- Published12 October 2016

- Published7 June 2016