Ian Brady: How the Moors Murderer came to symbolise pure evil

- Published

Ian Brady's notoriety and significance goes beyond the criminal to the political and the cultural

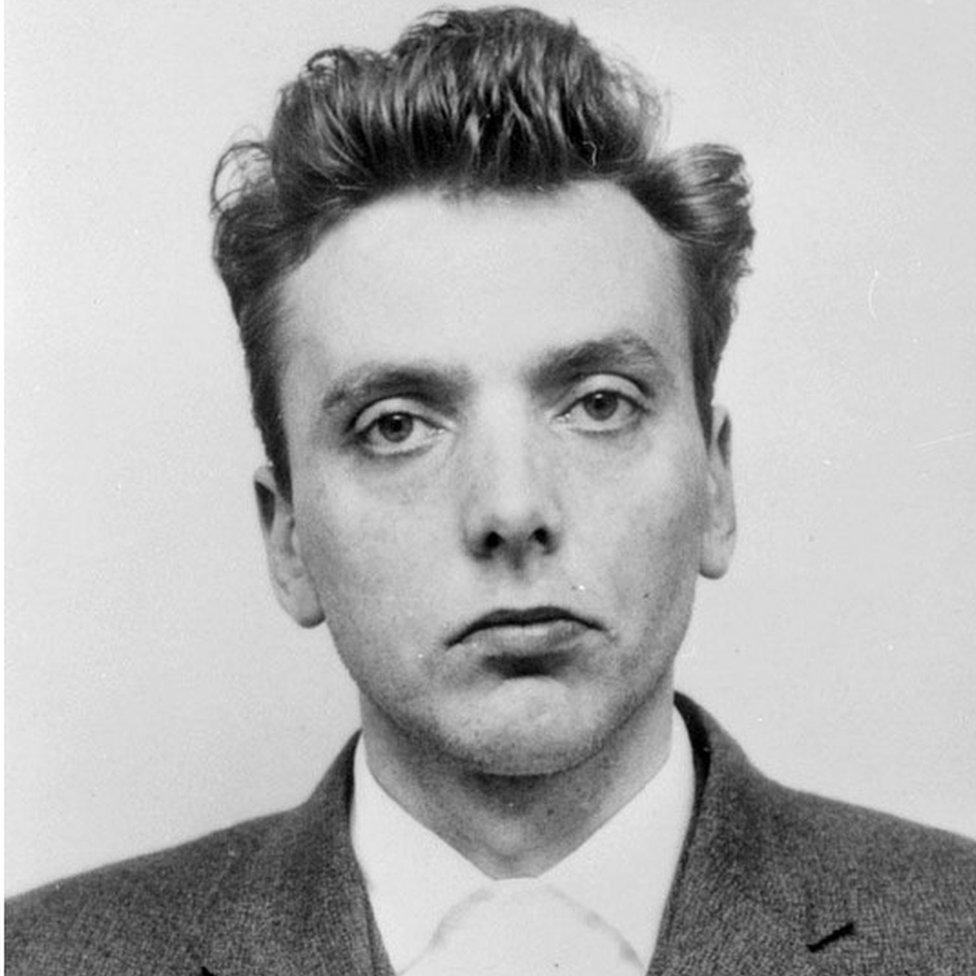

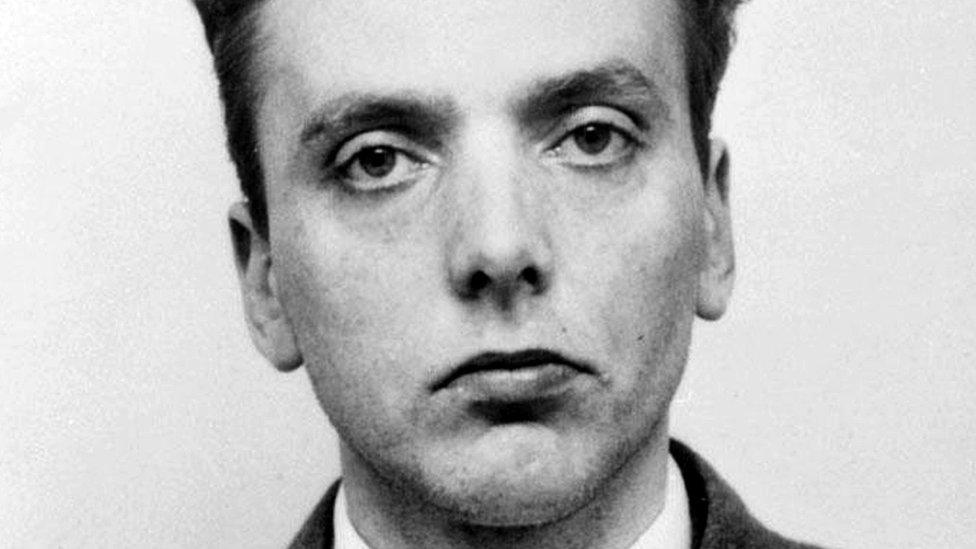

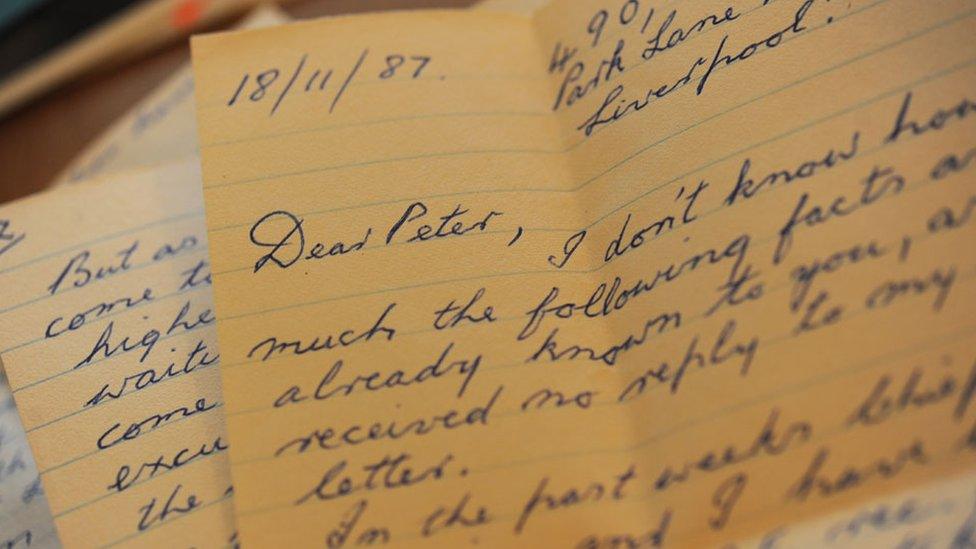

Ian Brady's mug shot has become visual shorthand for psychopathic evil. With his accomplice Myra Hindley, he occupies an especially ignominious place in our national folklore.

Margaret Thatcher described their crimes as "the most hideous and evil in modern times". A BBC News article in 2002, external suggested the so-called "Moors Murderers" had set "the benchmark by which other acts of evil are measured".

But Brady's notoriety goes beyond the criminal to the political and the cultural.

He became an important figure in 20th Century British history as a focus for debate about crime and punishment, good and evil, and the permissive society.

Brady and Hindley were charged with their crimes 11 days after the Murder (Abolition of the Death Penalty) Act had received royal assent in 1965.

They "cheated the gallows by a year" according to some, and were placed at the heart of a debate over capital punishment that would rumble on for more than a decade.

Moral panic

The horrific detail of their apparently motiveless crimes - the abduction, torture and murder of children and young people and the burying of the bodies on what the tabloids called "fog-shrouded wild moorlands" - was a horror story in the Gothic tradition that provided the perfect test of public opinion on ending the death penalty.

Police searches of Saddleworth moor began in the 1960s, including this area where the body of Lesley Downey was found

Successive home secretaries sought to reassure the public that, for the most heinous crimes, life imprisonment meant just that.

But Brady was more than just a debating chip in the argument over the hangman.

For many, he became a terrifying symbol of social upheaval.

'Poisonous flower'

His slicked back rocker-style hair and sociopathic stare chimed with the moral panic over youth culture.

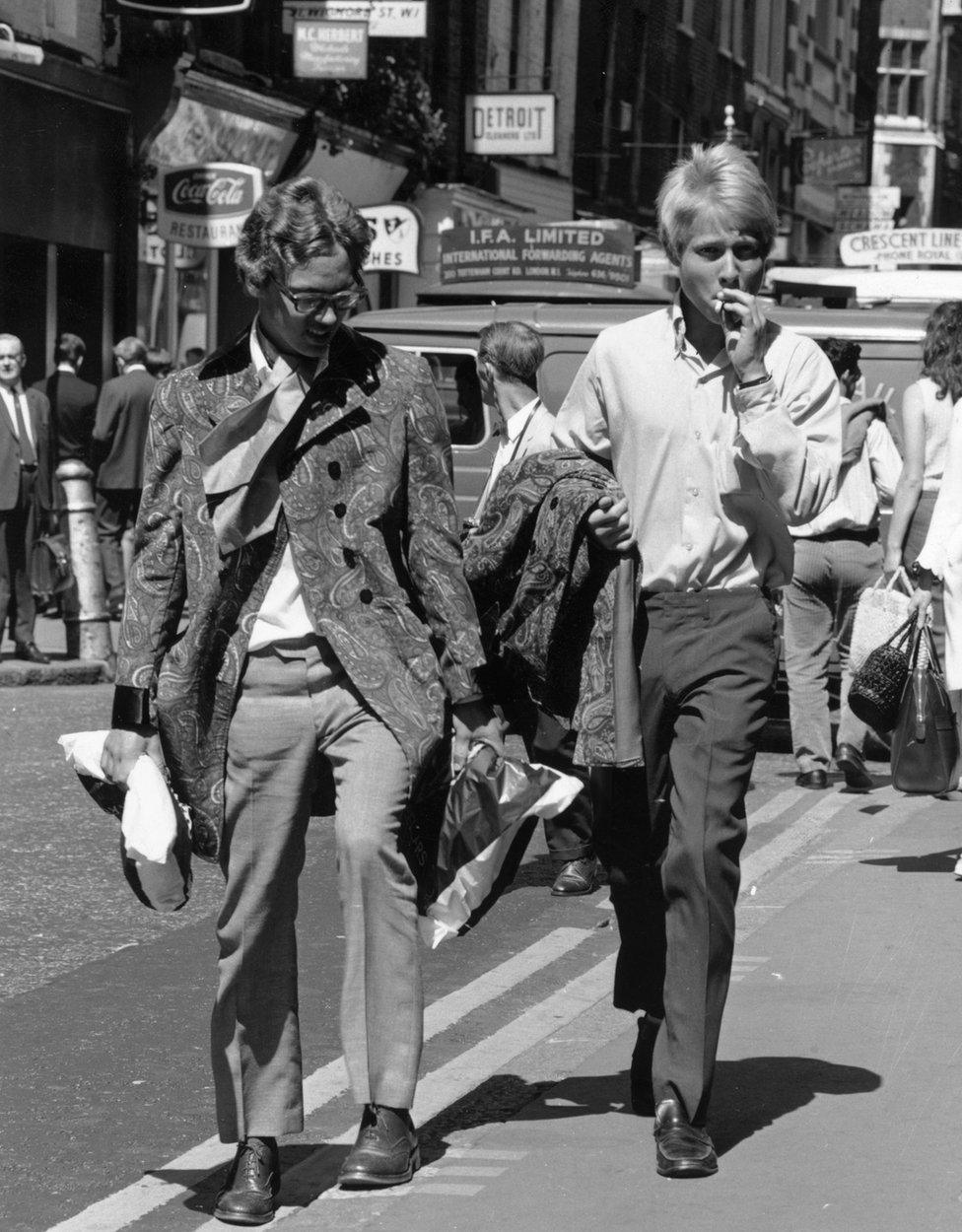

Mod and rocker clashes in the mid-60s were described by one newspaper as a symptom of the "disintegration of a nation's character".

Brady and his crimes were held up as the consequences of moral decay.

Writing about the murders, the novelist CP Snow argued that "permissive attitudes" were the "earth out of which the poisonous flower grew".

Brady's depravity was linked to fears about changing morality in the so-called Swinging 60s

The novelist Pamela Hansford Johnson - who was married to Snow - made a similar point in her book On Iniquity in 1967.

She suggested that Brady and Hindley's crimes had been an indictment of 1960s Britain.

"A wound in the flesh of our society had cracked open," she wrote. "We looked into it, and we smelled the sepsis."

Brady helped shape the age-old argument that permissiveness leads to violent crime.

Commentators noted how he had been born "out of wedlock" and had begun a life of criminality as a juvenile.

In the mid-60s, crime was rising rapidly and the face of the bastard Ian Brady was the backdrop.

He personified "pure evil" just as his innocent young victims personified "pure good".

For the press and politicians, the Moors Murderers were powerful examples of the clear but simplistic divide between the criminal underclass and the law-abiding majority, at a time when anxiety about law and order was rising.

Brady's fascination with Adolf Hitler and the Nazis confirmed the sense that he was the epitome of social depravity.

From his arrest until the day he died more than 50 years later, his haunting visage - along with that of Myra Hindley - have been routinely deployed as images of the threat.

He is the child snatcher, the bogeyman, the beast. He is the monster.

- Published16 May 2017

- Published15 May 2017

- Published16 May 2017

- Published16 May 2017

- Published16 May 2017