Passchendaele: Families remember relatives at Tyne Cot

- Published

Tyne Cot is one of more than 150 cemeteries around Ypres

Like most 20-somethings, soldier Edward Woolley was no stranger to heartbreak. His girlfriend, Bessie, had ended their engagement while he was on World War One's front line, near Ypres, in Belgium.

"If you see her again tell her I have got another girl, it makes no difference whether I have got one or not," 22-year-old Edward wrote to his sister, Rose, on 31 June 1917.

Weeks later, on 22 August, he was killed in the now-infamous Battle of Passchendaele.

A century on, his niece Ann Phillips has travelled from Somerset to Tyne Cot, a cemetery near Ypres, for a service to mark 100 years since the battle, which turned this region into a muddy wasteland.

She wears a white dress decorated with poppies as she finds her Uncle Ted's name on the cemetery's Memorial to the Missing, listed alongside 35,000 other missing soldiers.

"Mum always said he was the favourite of her four brothers," says Ann, 70, whose uncle made bicycles and lived in Bath before the battle.

"She thought it was a pity no-one had been out to pay their respects, but now I think, 'Well, Mum, we've done our bit, we've done what you couldn't.'

"The extent of the cemeteries has hit home quite how disastrous the death toll was in World War One," she adds.

Ann Phillips travelled to Ypres to remember her uncle, Edward Woolley

It is clear that Uncle Ted's story is just one family's tragedy among thousands.

Once a battlefield of mud, Tyne Cot is now an immaculately maintained cemetery.

It is one of more than 150 cemeteries around Ypres, all of which are carefully kept by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Nearly 4,000 relatives of soldiers have travelled here for Monday's service, but their numbers are dwarfed by rows of pristine graves and the imposing stone Memorial to the Missing.

A few miles away in Ypres, the city has hosted a weekend of song, poetry and plays, which told stories of heroism and sacrifice during battle.

But today strikes a solemn, more contemplative tone.

The service is reserved for Belgian and British royalty, and relatives of soldiers invited by the government in a public ballot to take part.

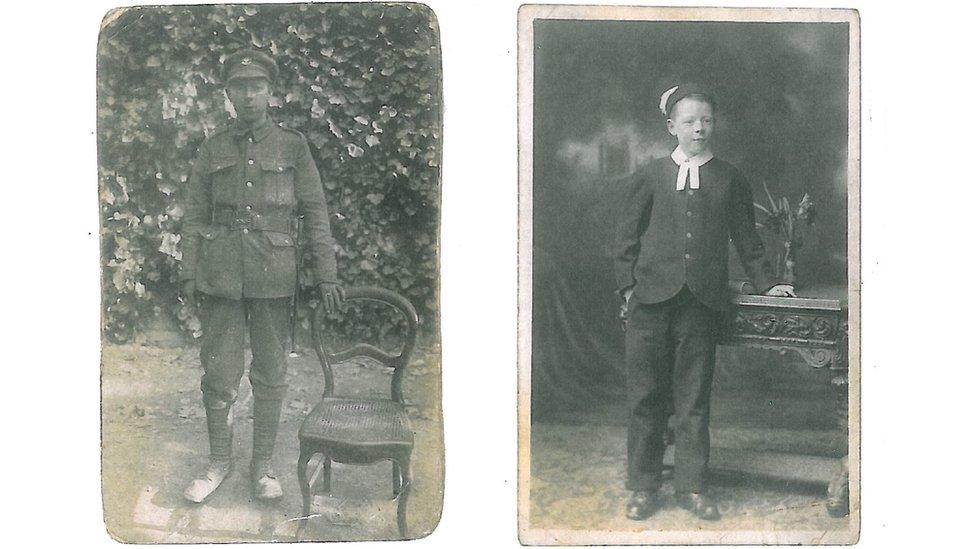

"Uncle Ted" in his military uniform, and when he was a teenager living in Bath

People are reading names on headstones before they take their seats.

Some of those who died are startlingly young - two graves are for boys aged just 17, while the memorial lists three missing soldiers who were 16 and presumably lied about their ages to fight.

'Overwhelming'

Many were a similar age to student Daniel Fay, 20, who is here with his dad, Stephen, to remember his great great uncle, James McBarrons.

James, 28, was a Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve and worked as a labourer in Paisley, but never returned from Passchendaele.

He died on 27 October 1917 from an abdominal wound, most likely from artillery.

"It's overwhelming to take in how much they gave," says Daniel, who studies illustration at Exeter University.

Daniel Fay travelled to the memorial with his dad, Stephen

"When you think of the Pals battalions, it makes me think of my group of friends who would have been the same age."

This is not Daniel's first trip to Ypres. He first went to the cemeteries in Belgium aged seven with his father, and the pair will spend the next few days "roaming around the different sites" in Belgium.

"You'd never have guessed there was a four-year world war that raged here," he says.

Daniel adds that his only wish is to learn more about James, whose brother Patrick also died in World War One.

Searching for Harold

Many people attending Monday's service have only recently discovered their connection to Passchendaele.

Cdr Fiona Shepherd, a Royal Navy logistics planner, has been piecing together the life and death of her great great uncle Harold Baker, from South Staffordshire, whose body was never found.

But she says a number of unknown graves in nearby Polygon Wood - a cemetery near Ypres with 87 war dead - are marked with Harold's regiment and she believes one is his final resting place.

Cdr Fiona Shepherd began her hunt for her great great uncle with a handful of photographs

Remarkably, Fiona managed to plot Harold's final advance in Ypres using British army war diaries and concentration returns, which show the location of bodies buried where men fell in the battle.

"I used Google Maps and tracing paper to find the route he would have taken on his last day, physically through the fields," she says.

"I probably got to about 100 metres to the spot at Polygon Wood where he was killed and found a shell just lying in a ditch, it was really quite poignant - it had been raining."

Fiona started her search with a handful of photographs of a man they wrongly believed to be called Reginald, as well as his home address in Liverpool.

She asked for help online and a woman in Liverpool, where Harold had lived, went to the local registry and found out his real name, leading to the discovery that he is remembered at Tyne Cot's memorial.

Vibrant and youthful

"It's hugely special to be here," says Fiona - who despite camping overnight in Ypres is wearing an immaculate military uniform.

"I wish anybody killed in those events could know that 100 years on all this effort is going in to commemorate what they did."

She says the photos are the only insight she has into what Harold was like as a person.

"We have no medal, diaries or letters," she says. "One shows a vibrant and youthful young man at a family wedding.

"We have another of him in uniform - probably from 1914 or 1915 - and he looks weary. He looks like he's seen something."

In a battle that left an estimated half a million soldiers killed, wounded or missing, it is no wonder that so many questions remain unanswered.

Places to look for your WW1 relatives

If you know the name of your relative, find out if they are buried in a Commonwealth war grave using this searchable list, external

Libraries hold archives of local newspapers, which may contain notices about your relative, or you can use the British Newspaper Archive, external

Find a birth, adoption, death or marriage records for your relative at the register office, external that would have been local to them

The War Office holds soldier service records, kept by the National Archives, which includes an individual's age, marital status, occupation and health - although many were damaged during Second World War bombing

War Diaries - narratives of events, usually kept by commanders - can contain details of losses, operational notes and maps. You can search by regiment, battallion or a place (e.g. "Northumberland")

- Published30 July 2017

- Published25 July 2017

- Published21 July 2017