'Legal high' review after laughing gas cases collapse

- Published

- comments

Empty canisters of laughing gas are a common sight in fields after music festivals

The Home Office says it will continue to prosecute those who sell nitrous oxide, despite the collapse of the first contested cases under new laws.

The Crown Prosecution Service is reviewing two cases after a judge and the government's own expert witness said "laughing gas" was exempt.

This now raises questions as to whether the new law will need to be amended.

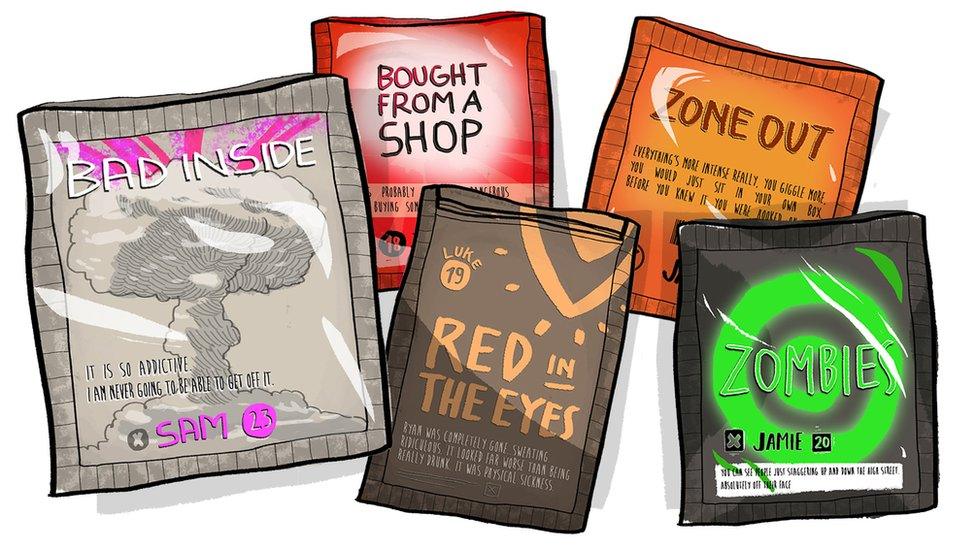

The Psychoactive Substances Act, external was introduced last year to deal with the problem of new manufactured drugs.

Nitrous oxide, also known as laughing gas, is taken by hundreds of thousands of people every year as a recreational drug. But the gas is also used by doctors for its pain-relieving properties.

In a statement the Home Office said: "Nitrous oxide is covered by the Psychoactive Substances Act and is illegal to supply for its psychoactive effect.

"However, the Act provides an exemption for medical products. Whether a substance is covered by this exemption is ultimately one for a court to determine based on the circumstances of each individual case".

A subsection of the Psychoactive Substances Act exempts medical products defined as "restoring, correcting or modifying a physiological function by exerting a pharmacological, immunological or metabolic action".

Music festival suppliers

A man was tried at Southwark Crown Court on Wednesday for intending to supply nitrous oxide at a music festival in Derbyshire.

But prosecuting barrister Adrian Fleming told the court that the Crown's own expert witness, Professor Philip Cowen, "is expressing the firm view that nitrous oxide, as the legislation is currently worded, is an exempt substance".

Meanwhile a judge at Taunton Crown Court, where two people were on trial for intending to supply nitrous oxide at Glastonbury Festival, came to the same conclusion.

In that second case, Judge Paul Garlick said "nitrous oxide is plainly capable of coming within the definition of an exempted substance… and in my view, on this evidence, it plainly is an exempted substance", according to Metro.co.uk.

Laughing gas: the risks

Laughing gas, or nitrous oxide, is used most commonly to provide pain relief during dentistry and childbirth.

Short-term exposure produces feeling of elation, but can also affect mental performance, dexterity and cause general disorientation and dizziness.

There is also a risk of oxygen starvation if the gas is consumed in an enclosed space, or from a plastic bag, which can lead to unconsciousness or death.

Long-term exposure can lead to Vitamin B12 depletion, which is linked to extreme tiredness, personality changes and concentration problems, and ultimately to severe nerve damage.

The two court cases have prompted a full review of the legislation by the Crown Prosecution Service.

The Psychoactive Substances Act was designed to deal with a wave of new manufactured drugs, often called legal highs, by banning any substance which "by stimulating or depressing the person's central nervous system... affects the person's mental functioning or emotional state".

The law specifically exempts alcohol, tobacco or nicotine-based products, caffeine, food and drink and medicinal products as defined in the Human Medicines Regulations 2012.

It is that last exemption that led the case to collapse.

The drug charity, Release, has described the law as "fundamentally flawed".

Its executive director, Niamh Eastwood, said: "The CPS must urgently drop all prosecutions under the Psychoactive Substances Act and review cases where defendants have previously pleaded guilty."

Mr Fleming told Southwark Crown Court that "Professor Cowen has expressed the clear view that nitrous oxide falls within the definition because of its analgesic effects".

"That may not have been the intention of those who framed the act, but the subsection clearly covers nitrous oxide."

The judge, David Tomlinson, instructed the jury to find the defendant - who cannot be named for legal reasons - not guilty.

Stressing that the hearing was not a "test case" and offered no precedent, Judge Tomlinson said the not guilty verdict could mean that either there was "a very lucky defendant or a number of other defendants will have their convictions quashed".

It is understood about 50 people have pleaded guilty to supplying nitrous oxide under the legislation, but this is the first time a defendant has contested the charge. Some lawyers are suggesting other substances may also be affected by the case.

Mr Fleming said the CPS had told him the situation demanded "a full review of the legislation and that will be carried out".

Embarrassment

Home Office crime survey figures published last month suggest 840,000 people in England and Wales used nitrous oxide in 2016-17. The silver canisters are a common sight at music festivals.

The gas was not considered harmful enough to be designated a controlled substance under existing drugs laws. In the last 10 years there have been 19 deaths associated with nitrous oxide, although a number of those are understood to have been suicides.

The collapse of two cases against people accused of intending to supply nitrous oxide is an embarrassment for the government, which had hailed the act as the answer to dealing with legal highs.

But during its passage through Parliament, ministers were warned that the law may be unworkable.

Drug experts say the big test of the legislation is whether lawyers can prove that a substance is "psychoactive".

Scientific tests

The Home Office is pinning its hopes on a new scientific experiment conducted in a test tube. The technique is designed to demonstrate whether a product binds to a particular receptor in the human body, affecting mental functioning or emotional state.

But ministers have been warned that such laboratory tests cannot prove that a substance affects the brain in a way that makes it psychoactive under the act.

Some experts believe the only sure way to demonstrate a substance is psychoactive is to scan the brain of a human as they take it, which is an impractical approach.

A similar problem blunted legal-high legislation in the Republic of Ireland.

- Published27 May 2015

- Published26 August 2016

- Published26 May 2016