Labour pledges to end in-work poverty in first five years

- Published

- comments

Labour is pledging to end in-work poverty within its first five years in office if it wins the next election.

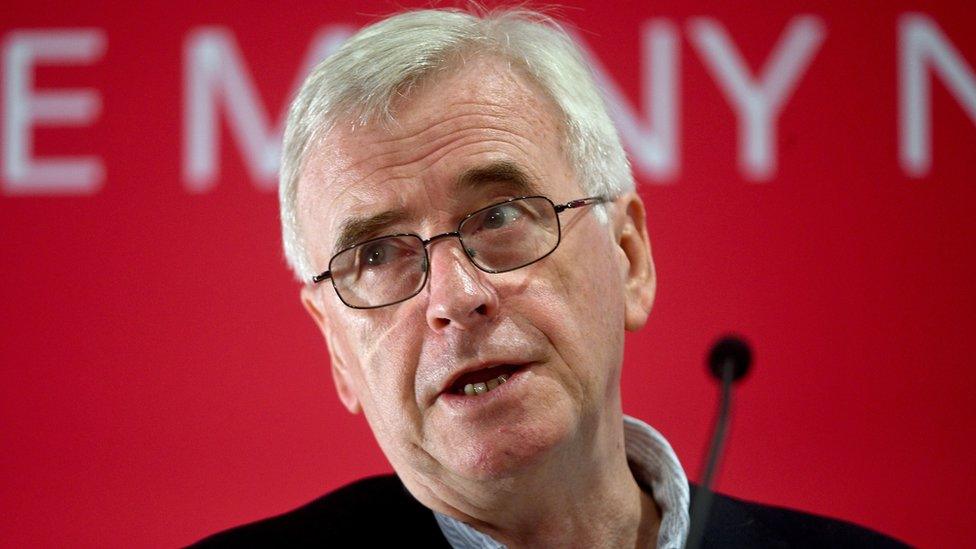

In a speech in London, John McDonnell promised to tackle the issue with a "structurally different economy", "public services free at the point of use" and a "strong social safety net".

This includes a "real living wage" and stopping the Universal Credit roll-out.

But the Conservatives said the policies would "harm the people [Labour] claim they want to help the most".

Poverty among people who are working has risen since the mid-1990s.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies said the proportion has gone up from 13% in 1994-95 to 18% in 2017, meaning about eight million people living in working households are in relative poverty.

A household is defined as being in relative poverty when its income is less than 60% of the average - less than £17,040 a year, on the most recent figures.

The IFS research said the rise had been partly driven by higher housing costs and lower earnings growth.

Speaking at the Resolution Foundation, the shadow chancellor said his goal was to eradicate poverty, since "nothing less should be the aim of a socialist government".

While the next Labour government would re-distribute income between the richest and poorest, he said this would only "paper over the cracks" unless there were major changes in the way the economy worked to address inequalities in opportunities and productivity.

He listed a number of policies - some which have been announced before - that he says will see a Labour government achieve their goal within a Parliamentary term of five years.

They include:

A network of regional public banks

Expanded trade union rights

Public services free at the point of use

Free buses for young people

Free childcare

Restoring funding for public libraries, leisure centres and parks

"Behind the concept of social mobility is the belief that poverty is OK as long as some people are given the opportunity to climb out of it, leaving the others behind," he said.

"I reject that completely, and want to see a society with higher living standards for everyone as well as one in which nobody lacks the means to survive or has to choose between life's essentials."

Pledging to end the "modern-day scourge" of in-work poverty, he added. "As chancellor in the next Labour government, I want you to judge me by how much we reduce poverty... how much we create a more equal society... by how much people's lives change for the better."

While immediately ending the most "damaging" aspects of Universal Credit, he said Labour would not seek to replicate the system of tax credits, designed to top up the incomes of the lowest-paid, introduced by Gordon Brown when he was chancellor.

Instead, a future government would "take a step back" and looking at designing a welfare system that helped people "find work and progress in work".

What counts as poverty?

The main way poverty is assessed is by using a relative measure - "relative poverty".

It's calculated by taking the median income in the country - that's the midpoint where half of the overall population have income more than that amount and half have less. It was £507 a week in 2017-18, external, or £437 after housing costs.

Then you take 60% of this middle amount and anyone who has less income than this is considered to be living in relative poverty.

In 1998-99, 34% of children in the UK were living in relative-poverty households. Today, this proportion is 30%, which represents about 4.1 million children.

Statistics on income after housing costs and benefits received are more widely used as this gives a better idea of how much disposable income someone might have.

But, some say relative poverty is flawed as a measure because the poverty line moves when average income changes. In times of recession, for example, when lots of people's wages decrease, relative poverty rates improve.

Campaigners say the benefit freeze in place for most of the past decade has been the biggest factor in exacerbating poverty levels among working families with children.

Rather than rising each year in line with inflation, to reflect the rising cost of living, most working-age benefits and tax credits have been frozen in value each year.

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation says this has pushed 200,000 people into poverty since 2016 and a further 200,000 could follow by 2020.

'Number one priority'

Claire Ainsley, the organisation's executive director, said ending in-work poverty should be the government's "number one priority after Brexit".

"In-work poverty is the problem of our times as millions have been swept into poverty through low wages, low hours and rising costs," she said.

Work and Pensions Secretary Amber Rudd has said it is "essential" that the freeze is lifted next year although she had acknowledged it will be up to the next prime minister.

But Conservative Party Chairman Brandon Lewis dismissed Labour's wider pledge, saying its plans for the economy "would lead to worse living standards".

He added: "Just this week we have seen wages rise by their fastest in 11 years, giving people more money in their pockets, and record numbers of people getting the security of a wage.

"Thanks to (the Conservatives') balanced approach, we've also cut taxes for 32 million people, taking millions of the lowest paid out of paying income tax altogether, and taken action to reduce the cost of living."

- Published28 March 2019

- Published17 July 2019