100 Women: The female protesters against giving women the vote

- Published

A century ago, after years of campaigning, women over the age of 30 who owned property were given the right to vote in the UK.

But for many thousands of women, it was not a moment of celebration.

Known as the anti-suffrage movement, these women had been working to oppose the suffragettes.

They believed women didn't have the capacity to understand politics, and portrayed the suffragettes as a group of "ugly" women and "spinsters".

The Anti-Suffrage League was founded in 1908 by Mary Humphrey Ward, with support from two men: Lord Curzon and William Cremer.

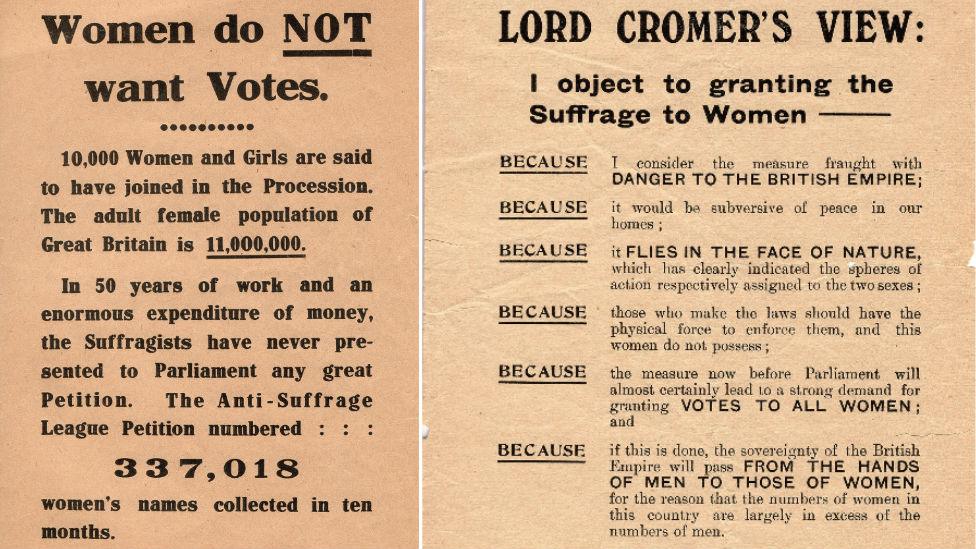

A year later, it was announced that more than 250,000 people, both men and women, had signed a petition against giving women the vote.

Writing in The Queen in 1908, external, one "opponent", as they were described in the article, said they saw the campaign for the vote as a "prelude to a social revolution" that would set society back.

"We believe in the division of functions as the keystone of civilisation," the piece continued.

"It is as if the animals on the farm should insist on changing places - the cows insist upon drawing the coach, while the horses strive in vain to chew the cud and ruminate."

Historian Kathy Atherton says people nowadays can find it "surprising" that women were involved in an anti-suffrage movement, but that it's important to "put yourself in their shoes".

"There would have been a general acceptance that women were intellectually inferior and emotional - and women would have believed that as well as men - so they didn't have the capacity to make political judgements," she says.

"It's a really hierarchical society and the white male is at the top of the heap.

"There's a fear that you're upsetting the natural order of things, even going so far as thinking the colonies would be affected if they felt that Britain was being ruled by women."

"One of the arguments that some of these anti-suffrage campaigners put forward was that if we give British women the vote - and they would very specifically use the example of India - Indian men and women won't like it," says Dr Sumita Mukherjee from the University of Bristol.

At the time, India was ruled by the British Empire so power was exerted by the government in London and, by default, those who voted for them in the first place.

"They [the anti-suffrage movement] used this assumption that colonial subjects were very patriarchal themselves and they wouldn't like it if women had the vote in Britain," says Dr Mukherjee.

"The counter-argument was that there had been a female queen, Queen Victoria. She'd been Empress of the British Empire and most subjects hadn't kicked up a fuss about having an empress so why would they kick up a fuss about British women having a vote?"

There were also arguments much closer to home.

Historical author Elizabeth Crawford says there was a genuine concern at the time that giving women the vote would "destroy families".

"They thought it would cause dissension in the home if a man wanted to vote conservative and his wife liberal," she says.

The writer in The Queen magazine said the suffragettes were "irresponsible" in forcing the vote on wives and mothers.

"It is a vast upheaval of social institutions and habits, which must cut into the peace and well-being of families and harm the education of children," the article claimed.

A leaflet from 1909, external held in The Woman's Library puts forward an argument that women have "neither capacity nor leisure" to vote.

"Women are more easily swayed by sentiment, less open to reason, less logical, keener in intuition, more sensitive than men," the writer claims.

"The qualities in which their minds excel are those least required in politics; their strong points are wasted or harmful there."

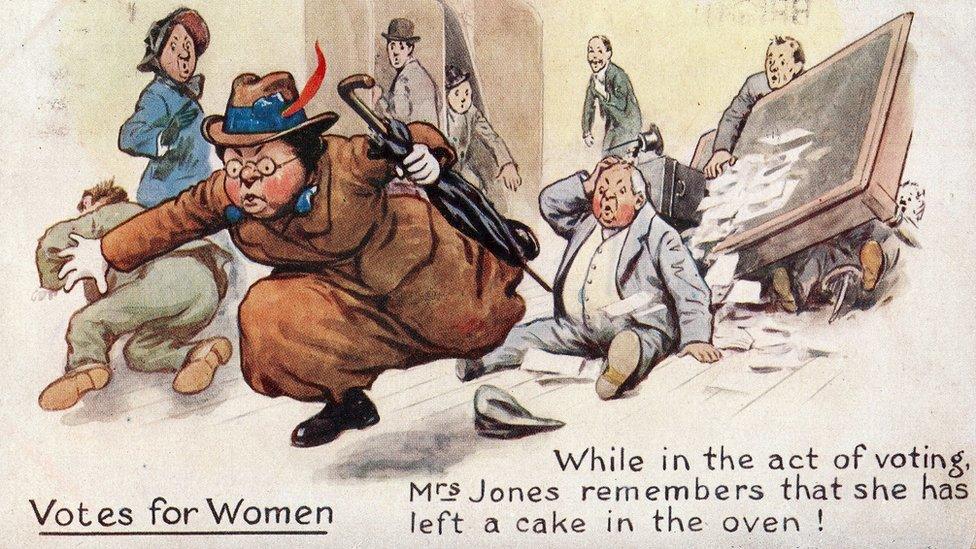

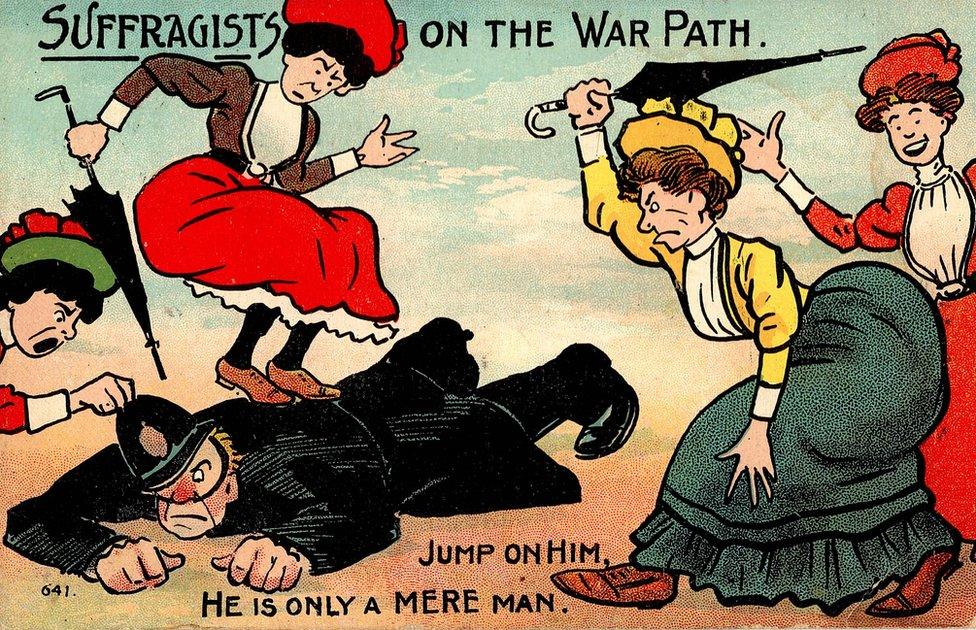

Both sides of the campaign produced artwork and slogans to promote their points of view.

"They [the anti-suffrage images] are portraying the suffragettes as being absolute harridans, slovenly housewives, appalling mothers, that they were ugly, that they looked like men, that they were lesbians," says Ms Atherton.

"It's very much like the Twitter campaigns that you get at the moment, whenever a high-profile woman says something of a feminist nature."

Prof June Purvis of the University of Portsmouth has collected many postcards printed with anti-suffrage messages and imagery.

"I was quite fascinated by these postcards because not many people have done research on them, and I thought they were telling a message of how difficult it was for women at that time to be taken seriously," she says.

A number of the examples in her collection still have original writing on the back, many of which don't explicitly refer to the image on the front.

"In the early 20th century postcards were big business," says Prof Purvis.

"I think the people who bought them were sending a normal message [for example arranging to meet up], like how we now use email."

For Prof Purvis, one of the stand-out postcards shows a group of women, supposedly in the House of Commons, showing what a future with women in Parliament would be like.

In the image, one woman is staring into a hand mirror, while another reads a book in the corner and yet another has brought her baby with her.

"That postcard really portrays the cultural fear at the time, that if women got the vote, they may then ask to be allowed to stand for Parliament and this is going to upset the whole gender order."

In November 1918 women were granted the right to stand for election for the first time.

What is 100 women?

BBC 100 Women names 100 influential and inspirational women around the world every year and shares their stories. Find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external and use #100Women

Other stories you might like:

Egypt's first female Premier League footballer

- Published6 February 2018

- Published6 February 2018

- Published6 February 2018