Suffrage: The journey towards 50-50

- Published

A re-enactment of a suffragette protest outside the Houses of Parliament

If my five-year-old self had been told that my great-grandmothers weren't allowed to vote, I'd have thought that was pretty daft.

I grew up with a female prime minister in charge. It would have made no sense to me whatsoever back then to discover that women hadn't had a say.

If Mrs Thatcher wasn't always given a fond reception in Glasgow in the 1980s, it wasn't because she had a particular kind of chromosomes. And growing up - I suppose like many women of my generation - our expectation was that if you worked hard enough, women could more or less have it all.

That sense of what was possible grew with the size of Sue Ellen from Dallas's shoulder pads, followed later by the Spice Girls' cartoonish power. The fictitious Mrs Banks in Mary Poppins seemed to rather enjoy dashing off to suffragette rallies (whatever they really were), which of course she could do only with the help of her nanny to look after her children.

But to learn about the history of the fight for the vote back then seemed like a study of a weird injustice overturned from another world, not anything that could be in the memory of anyone's lifetime. Interesting to learn, yes, but relevant? It didn't necessarily seem so.

Well guess what? I can't be the only person in the world to have discovered as I grew up that life was a bit more complicated than that, and opportunity for women wasn't really going to be defined by Kylie Minogue's example of switching careers when she fancied it. Personal choices were a lot more complex. And yes, reality crept in - women were, and are, treated differently in so many parts of life. Without question, that decades-long struggle finds its own echoes today.

I'm writing this late at night on a bus speeding along a four-lane highway in China. It's full of officials from No 10 and other British journalists. We're all trailing the convoy of the UK's second female prime minister, who saw off another woman for her job (although who knows what might come next), following her every move in a trade mission as she escapes the political maelstrom for a moment.

And while there are plenty of women in this travelling version of the Westminster bubble, here, as time and again in our politics, it is a long way off from being one-for-one.

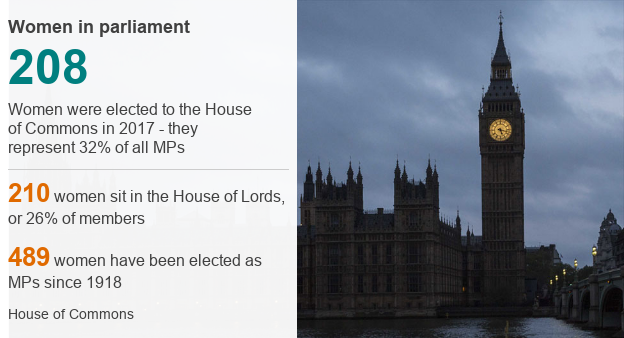

In politics at least, it is abundantly clear that big changes have taken place. Parliament does now look more like the population. There are 208 female MPs at the moment, that's a record level. But it's still not quite a third, and well short of reflecting the population.

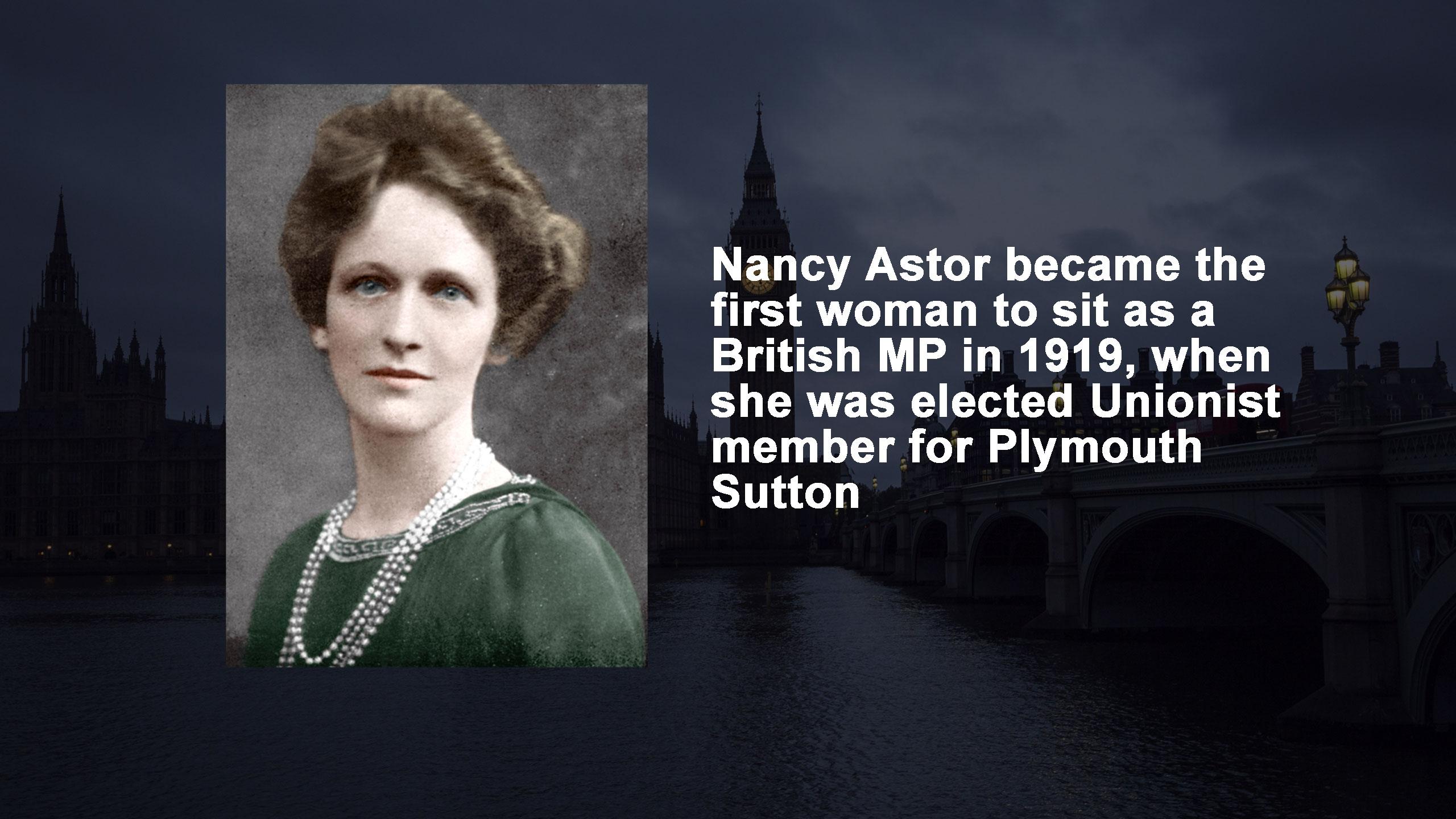

It's a long time since the first ever MP was elected, in 1918, a long time since 19 MPs were voted in at the 1979 general election alongside the country's first female political leader, the 60 women elected in 1992 or even the dramatic doubling in 1997. Life is about more than just numbers, of course, but does the proportion of women sitting on our green benches really matter?

Forty five women have served as cabinet ministers (pictures: Getty Images & PA)

The argument is made, by most politicians certainly, that we should be aiming for something much more like 50-50. But the parties have different approaches to how to hit that mark.

Labour has pursued an active strategy for many years, where only women are allowed to stand for some seats. The all-women shortlist was much argued over to start with. And as times move on there's a new pointed question, dragging in the debate over the status of transgender candidates.

The Tories have worked more informally, using support networks and gentle encouragement - and that has often been important too. Interestingly, many female MPs who give wholehearted backing to Theresa May came to know and like her through her work over the years as part of their organisation, Women To Win.

But why should they make the effort, and does it matter to you? Certainly most voters have got many more things to worry about than gender equality in politics. Remember, it took years and years for the campaigns of the suffragettes to cut through.

But if we want our politics to represent all of us fairly, consider this. If you are reading this with female eyes then I guess, like me, you're no stranger to being the only woman in the room. It's not necessarily bad, or good, sometimes it doesn't occur to you at all, but sometimes it is glaringly obvious, and rather different.

If you are a man reading this, what does it feel like if you are the only one in a room full of women? Again, whether you like it or loathe it, you may not always notice, but when you do, sometimes it can feel pretty different.

As human beings, we all know that different environments and different contexts lead to different conversations. Think back to when women were forbidden from having a say in who ran the country. Were their voices heard, their hopes and fears fully taken into consideration?

With the glorious benefit of 100 years of hindsight, the answer to that is a straightforward no. A century on, is it so strange to hope that everyone can be represented in any room?

That's not to say for a second that women's concerns are all the same. But in the most straightforward of terms, if you want a system to be successful, why would you not want to include as many people as possible? Does a democracy inspire faith, if some of its members feel no-one is listening?

As this anniversary approaches it is not simply a question of commemorating an achievement of days long gone. The best tribute maybe is to remember suffrage's most simple message, to give everyone a say.