Reality Check: What if women hadn't been allowed to vote?

- Published

It's 100 years since some women (and all men) were finally given the vote. But how might political history have been different if they hadn't won suffrage?

In the real world, the Conservatives couldn't win a majority at the 2017 general election.

But what would happen if all the votes cast by women were removed from the equation? Because of different patterns in how men and women vote it is likely the result would have been different and Prime Minister Theresa May would have had a majority.

The results of some other elections would probably have been different too in this alternate reality.

It's important to be clear about the limitations of what we can know here.

The secret ballot means we never have definitive figures about how men and women vote. We are reliant on studies that involve asking a sample of the population how they voted after elections have taken place.

The gender gap in voting is fairly small. Other demographic factors have a far bigger impact on people's likelihood to vote for each party.

In the past, social class was a dominant factor. Middle-class people were more likely to vote Conservative and working-class people were more likely to vote Labour.

Women at a polling station in 1983

Recently that's changed. In 2017, age and education were far more important. Young voters and voters with degrees were more likely to back Labour. Older voters and those with fewer qualifications were more likely to back the Conservatives.

But how do the sexes differ when it comes to elections?

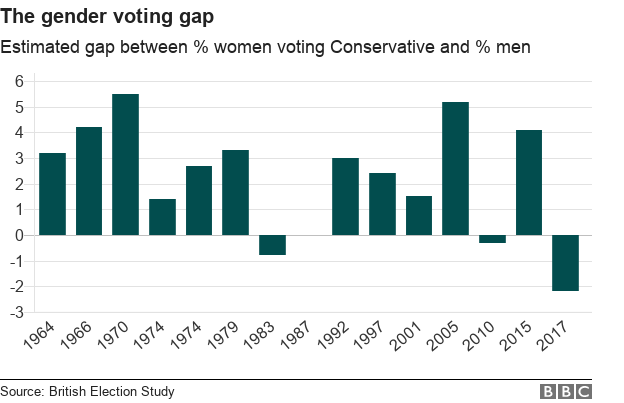

If we look back over time the gender gap in voting has changed.

The British Election Study has data going back to the 1964 general election. In the 1960s and 1970s it found that women were more likely than men to vote Conservative and less likely to vote Labour. It's not easy to find a definitive explanation.

Voting behaviour expert Dr Rosalind Shorrocks, from the University of Manchester, says that one of the reasons behind the difference was that women were more religious than men, and also points to the way they were affected by government policies.

"The Conservative Party's post-war anti-rationing stance appealed particularly to housewives who were managing family budgets," she explains.

So in a close election like 1970, it was probably women voters who sealed the Conservative victory.

That trend evaporated in the 1980s - interestingly when the prime minister was a woman - before returning in the 1990s.

At recent elections the pattern seems to have become more volatile, like other trends in voting behaviour.

In 2010 there was very little difference between men and women in terms of the two main parties. But women were more likely to back the Liberal Democrats and less likely to back smaller parties.

The gender gap for other parties became more pronounced in 2015. This was connected to UKIP's very strong showing. They received 13% of the vote overall but were considerably more popular among men than women.

That meant that women were more likely than men to vote for both Labour and the Conservatives.

So if women had been unable to vote, it's quite likely that UKIP would have won more than the single seat they did. Nigel Farage might have become an MP.

Douglas Carswell (left) and Nigel Farage campaigning in 2014

In 2017 the pattern changed again. The British Election Study and other post-election surveys suggest that the gender gap was the opposite of what it used to be.

Women were more likely than men to vote Labour and less likely to vote Conservative.

That is likely to have swayed the overall result. The Conservatives were only eight seats short of an outright majority and there was an unusually large number of seats where they lost very narrowly.

So if women had not voted, Theresa May would probably have had more Conservative MPs and British politics could look very different.

Again, Dr Shorrocks says this could be down to the perceived impact of government policies.

"In 2015 and 2017, it is especially younger women - under the age of 40 - who were particularly supportive of Labour.

"This is likely to be due to the disproportionate impact of austerity on women, with younger women the most likely to say that their cost of living has gone up and quality of services such as the NHS has gone down under the Conservative government."

- Published6 February 2018

- Published6 February 2018

- Published5 February 2018