The Syrian refugee who feeds everyone she meets

- Published

She was alone, separated from her children, without her home or work. But facing circumstances that could break even the strongest spirits, Majeda refused to give in. She turned to something she hoped would build her a new life - food.

The first big dinner Majeda Khoury hosted was a strange one - the menu was unappetising and the guests of honour couldn't attend.

Though she had arrived in Britain just five months earlier, the long guest list she put together was one to be proud of.

Two speakers appeared on a screen via Skype in the comfortable London venue. When guests looked past the face of one, a mother of three, they would see grey, shell-pocked walls.

Live from war-torn Eastern Ghouta, Syria, the doctor and activist explained to their fellow guests what civilians there were living through - a five-year siege, hunger, destroyed hospitals, chemical attacks, and brutal shelling by President Bashar al-Assad's government. Just leaving the house could get them killed.

As the diners listened, they ate a thin soup "because that's all there was to eat in Eastern Ghouta". Majeda, 46, remembers that she left the event happily carrying more than 100 letters asking the British government to take humanitarian action.

Majeda Khoury with her sons, Hadi and Karim

Though something as simple as a sharing a dinner table will not solve the refugee crisis, meals like this are how Majeda, a Syrian human rights activist who fled to Britain in 2017, finds a place in the hearts of strangers she meets.

Feeding people gives her a way to tell her story. It helps her continue the work for which she was persecuted at home.

Crucially, deprived of mothering the sons who adored her cooking and are now growing older in Damascus, food has helped Majeda build a second family, made up of new friends.

Majeda never wanted to live in Britain. Before the uprising in her country, she led a privileged life as a children's counsellor running a family education centre. She took pleasure in raising her boys, Hadi and Karim, and together with her husband, they lived in a "beautiful home" in Damascus.

When pro-democracy protests broke out against President Assad's rule in 2011, she joined them, but she stopped as the uprising spiralled into conflict. Instead, she worked to help victims of the war. But in 2015 she was imprisoned after helping to feed refugees arriving in her city from other parts of Syria.

The government, like other groups, was accused of using food as a weapon and preventing supplies reaching areas where people opposed it. "But as a wealthy, Christian woman, I could pass through checkpoints. And so I used to smuggle bread to feed people. I couldn't watch them starve," Majeda says.

Fearing for the safety of her own family, Majeda fled to neighbouring Lebanon, leaving her sons behind with their father. They were 13 and 15.

Being an activist in Lebanon was risky, but she persisted and in 2017 was invited to speak at a conference in the UK. While in Britain, Majeda got news that her colleagues were being arrested and, believing she was in danger, she sought political asylum. From working to protect refugees, she became one of them, dislocated indefinitely from family and home.

The first weeks in Britain were extremely difficult. But she quickly realised that the cuisine of her home, Damascus, one of the world's oldest cities, had an audience in London.

Food is a cornerstone of Syrian culture and family life. It's often elaborate and complicated, fiddly and full of rich and colourful ingredients - red pomegranate seeds that shine like jewels, purple fleshy aubergines, green fresh Aleppo pistachios, golden tahina sauce from sesame seeds. It is said that the "eyes eat before the mouth".

Most women in Syria do not work - in 2013 14% of the workforce was female, external - and so they still do the vast majority of cooking and housework.

You might also be interested in:

"Our kitchen was twice the size of kitchens in the UK - it's a very important part of a Syrian house. I cooked for my husband and my children - they loved my food, especially how I present meals," she says.

Before war disrupted normal life, a wife or mother could spend hours each day chopping, peeling, stuffing, roasting, and rolling ingredients.

Kibbeh is one popular snack - a deep fried ball of meat and nuts that needs nimble and skilled fingers to prepare. One cookbook from Aleppo lists 26 varieties but it's often just one of many dishes on a dining table.

"Syrian women are very patient because we have to make a lot of dishes. For example, we spend three hours making yebra [vine leaves] - and then they eat it in seconds. We don't use measuring spoons - we just know what should go in," Majeda says, laughing.

Majeda preparing chopped parsley (top middle), tahina (top right), maqluba (bottom middle), fried onions (bottom right)

Asylum seekers in the UK are not allowed to work and Majeda spent her first year in London relying on the generosity of strangers, moving home five times.

In each place, she made sure no-one went hungry. Although, as any cook knows, adapting to someone else's kitchen and habits is no mean feat.

She stayed first with an Italian-French couple. "They had a fantastic kitchen, small but full of equipment. We had a competition every night, taking it in turns to see who could cook better." Realising she was separated from her family, Majeda's host, a photographer, surprised her by framing pictures of her children.

In another place, she ate lunch every day with the host, who had retired while his wife continued to work. "We remain friends now and they send me messages about how much they miss my food."

She also lived with another Syrian woman, feeding her children while she was at work. "I still send them food parcels when I make something I know they like."

"I felt able to give something back to the people I stayed with."

She also met old-timers and new arrivals in the growing Syrian community in London. "There are many students here alone, so I asked them, 'What do you miss from your mum's cooking?' and I did it for them instead."

But while Majeda cooked for other people's children in Britain, her husband had arranged for someone else to make meals for their sons. Karim, the youngest, took an interest in food and sometimes called Majeda to ask for recipe advice.

"It made me feel very, very sad - I missed my children. They were without their mother - and here I was cooking for strangers. It was very emotional. I thought to myself, one day they'll come here and I'll be able to cook for them again."

Majeda struggled to forget her fellow Syrians whom she felt she had "abandoned".

"I had no right to leave. I feel guilty, because it was people like me that started those demonstrations [against the government] and then we left. I felt so far away from them and their suffering. I wanted to carry on my work" she says.

Majeda preparing harra esbou, made with lentils, pasta, tamarind, pomegranate, onions and garlic

As an asylum seeker from a wealthy, urban background, Majeda is in a stronger position than many Syrian refugees in the UK. Most are eligible to come to Britain due only to disabilities or health problems, causing them to be selected for the government's Vulnerable Person Resettlement Scheme.

Majeda speaks good English and her confident and commanding presence makes it clear she is used to people listening to her.

One of her early decisions in London was to join a refugee cooking group run by social enterprise Migrateful. It brings together Londoners and refugees to learn recipes and share a meal.

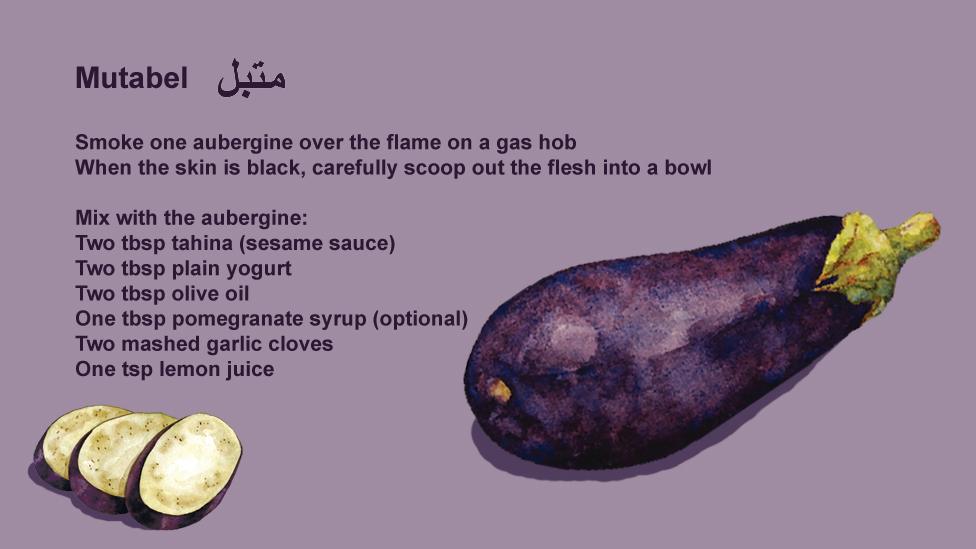

She gives one or two classes a week, teaching simple but beautiful meals that can be reproduced at home. One of the easier dishes is mutabel, which is made by blending smoked aubergine with tahina (sesame sauce), yogurt, lemon, pomegranate syrup and garlic.

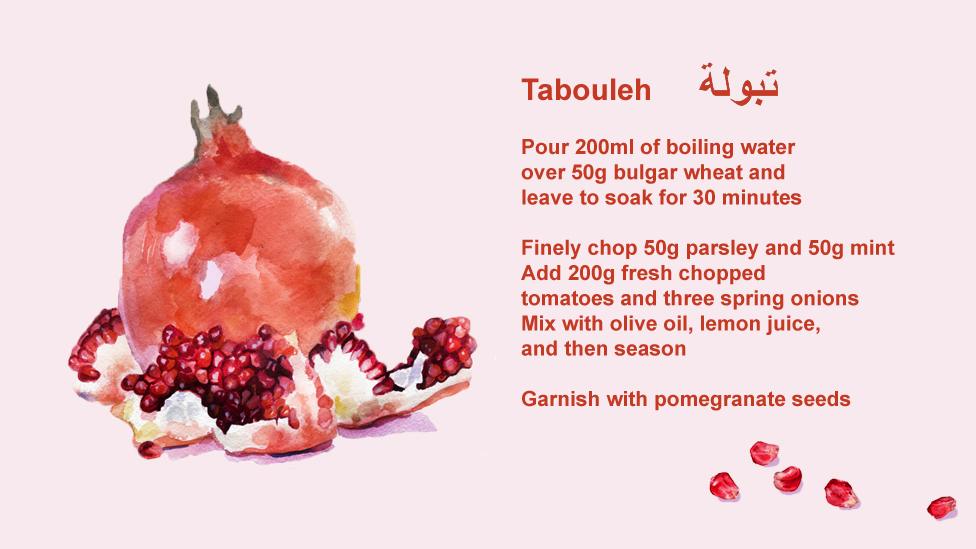

Another is tabouleh salad. Students must chop the parsley leaves "very very finely", mixing them with bulgar wheat (a grain similar to couscous), tomatoes, and spring onions.

One meal that she says everyone loves is harra esbou, or "he's burnt his fingers", a nod to how tasty it is. A traditional Damascene dish with a "sweet and sour" taste that comes from strained tamarind and pomegranate syrup, it's made with lentils and pasta, adorned with garlic, coriander and fried bread.

Tabouleh (L) and mutabel (R) prepared by Majeda

When she first arrived, Majeda wanted to tell everyone she met about the war, believing they didn't understand the full picture. She found that it depressed or fatigued people.

But when she started to teach, she discovered the dinners gave her an opportunity to really talk and to continue her activism. Over food, she describes how civilians are targeted in Syria's war and how the pro-democracy movement was "crushed by President Assad".

A lesson in politics over dinner may not be everyone's cup of tea, but Majeda says that most people are receptive. "Food is very important. When you share food with people, they will care more about you and listen to you."

Picking up on a trend in the capital for Syrian cultural events to raise money for refugees, she also started a monthly supper club. Some of the feasts mark events such as Easter or Eid at the end of Ramadan and they quickly sell out.

Cooking the food she is so familiar with is comforting and cathartic - but it also gives her dignity in the face of pity she feels from organisations or people who see refugees as "helpless" charity cases.

It's a link to the home she never wanted to leave. But it's also a lifeline, her way of meeting people and finding a purpose in exile.

In April this year, Majeda laid the dinner table in another unfamiliar house. After months of waiting for a family reunion visa, her sons were finally joining her.

London's high rents made it hard to find a place for them to live but a Syrian-Irish couple invited them to stay for a few days for the reunion. "They knew I wanted to be prepared and to make a meal for my children. They have a very special kitchen. They took me to a Syrian store so I could buy what I needed to cook."

"I made my sons' favourite dish, shakriyeh [lamb cooked in yogurt with rice], with mutabel and tabouleh salad. It was really a fantastic dinner that we all shared together."

The teenagers, who learned English at school in Syria, are shy but adapting to life in the UK. "My family like British food because it's full of fat - they like fat," she says. "I made English breakfast for them when they arrived but personally my stomach can't cope with it."

Majeda says she wakes up every day hoping that she can return to Syria. She doesn't want the country "left in the hands of the government".

But she is also hoping to start a catering business in London, renting a kitchen and offering employment to other Syrian women. She thinks her country's food is growing on the capital.

When Majeda, Hadi and Karim finally moved into their own place recently, she held a housewarming party. Guests brought gifts to help them feel at home. Knowing their friend, they brought her pans and pots, knives and chopping boards, everything a good family kitchen needs.

Images by Emma Lynch