The drugs being used at UK festivals

- Published

Over the summer, thousands of people will flock to festivals to socialise and enjoy music. Despite all the warnings, some will take drugs - but what do we know about the substances being used and the risks they pose?

In May two young adults died at the Mutiny dance music festival in Portsmouth, after organisers issued an alert about the availability of dangerous drugs at the site.

The parents of victims Georgia Jones, 18, and Tommy Cowan, 20, warned others about drug use, but such stories are not uncommon - every year we hear of people dying at festivals.

Knowing more about what people are using - and what the risks might be - is crucial to protect them from harm.

Who is using drugs?

Up-to-date information about the drugs being used at festivals and the number of people taking them is limited.

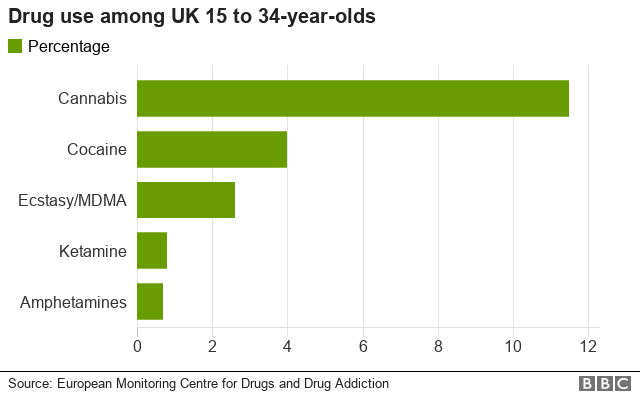

However, as a large proportion of people at festivals are under the age of 35, external, drug use figures for UK 15- to 34-year-olds from the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, external (EMCDDA) may give some insight.

These suggest that across the population as a whole, illegal drugs are used by a minority of young adults.

The most common, cannabis, was used by 12% of people in this age group in 2017, while cocaine was used by 4%, ecstasy by 3% and ketamine and amphetamines by 1%.

It is thought that rates of use are higher among clubbers and festivalgoers than the population as a whole.

But figures from 10 major UK festivals between 2008-11 showed that seizures of drugs fell rapidly over the period, external.

A later Freedom of Information request for drug seizures at the Glastonbury Festival between 2014-16 showed a sharp fall in the number of arrests but a rise in the amount of cocaine, ecstasy/MDMA and ketamine confiscated by police, external.

Stronger drugs

Perhaps the most worrying trend is the recent rise in deaths attributed to club drugs, notably ecstasy and cocaine.

Deaths in England and Wales linked to ecstasy pills, external reached their highest level in 2016 at 63 - up from 10 in 2010.

Meanwhile, the number of cocaine-related deaths rose from 112 in 2011 to 371 in 2016, external.

The number of people using drugs such as cocaine and ecstasy has remained largely stable, which suggests that the rise in deaths and hospital admissions is not down to more drugs being used.

Instead, the big change has been a dramatic rise in purity and strength.

For example, while the average content of MDMA, external - the active ingredient in ecstasy pills - was between 50mg and 80mg in the 2000s, it is thought that pills in Europe now contain an average of about 125mg. "Super strength" pills containing over 270mg have also been seen.

Another worrying development is the emergence of so-called new psychoactive substances - synthetic drugs made in laboratories, designed to mimic the effects of "traditional" substances. By 2015 the EMCDDA was actively monitoring more than 450 substances, external, with the potential risks varying with each one.

Often, they can have the same appearance as "traditional" drugs - frequently fine white powders - allowing them to be intentionally mis-sold to unwitting customers.

The problems caused by drugs

Cocaine: Overheating, paranoia, psychosis-like experiences, heart failure, nasal damage, dependence

Ecstasy/MDMA: Dehydration, overheating, panic attacks, heart attack, stroke, psychosis-like experiences, low mood in days after use

Ketamine: Accidents, psychosis-like experiences, severe bladder problems, nasal damage, dependence

Amphetamines: Heart problems, overheating, anxiety, high blood pressure, psychosis-like experiences, dependence

Cannabis: Paranoia, psychosis-like experiences, anxiety, lung damage, nausea, dependence

Alcohol: Accidents, nausea, high blood pressure, strokes, liver damage, cancer, dependence

Source: The Loop, Talk to Frank, NHS Choices

Ultimately, no drug use can be considered truly safe and the only way to avoid the risk of harm completely is to avoid using them.

However, the reality is that, for some, drugs and festivals go hand in hand.

Drugs campaign group The Loop has previously tested the contents of substances seized by police and security at events but wants more festivalgoers to be allowed to have samples tested themselves.

It offered the service at a number of events last year and says that where this has happened about 20% of people decide not to take their drugs, external after hearing the results.

This year, Bestival has said that although it "strongly advises festivalgoers to avoid taking any illegal substances", it will allow testing by The Loop to give people "the opportunity to make informed choices". Local police are aware and say they "are exploring all safety options".

The Loop, which has said people who do use drugs should take only a small amount to test how it affects them, external, also issues alerts via social media about potentially dangerous adulterated or high-strength batches they have identified.

However, some festival organisers have previously called for police to clarify whether they support offering testing to festivalgoers and have raised concerns that the results "have the ability to mislead", external. The Home Office has said "no drug-taking can be assumed to be safe".

Those who do decide to keep their drugs after testing cannot be certain about all of the drugs they have.

Substances can vary markedly in their content even within the same batches. And popular designs of pills, including logos, are often copied. It is not possible for someone to know all the pills they have are the same.

Combining different drugs can cause very dangerous interactions.

It would be an oversight not to mention the most ubiquitous festival drug - alcohol.

Across society, it causes more harm than any other drug and has been linked to 337,000 hospital admissions in England in 2016-2017 and 5,507 deaths in 2016, external.

Almost six out of 10 UK adults drink alcohol weekly, external and at festivals it is not unreasonable to assume that many people will be drinking more than usual.

So, while some festivalgoers need to think very carefully about banned substances they plan to take, the problem facing a greater number will be making sure they don't overdo it on the drink.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from experts working for an outside organisation.

Jon Waldron and Prof Val Curran, external are members of the Electronic Music Scene Survey, external team, a European research project (funded in the UK by the Department of Health) and based at the Clinical Psychopharmacology Unit, University College London.

Edited by Duncan Walker