Cruise ship rescue: How to survive for 10 hours in the water

- Published

'I am very lucky to be alive'

A British woman has survived for 10 hours in the sea off the coast of Croatia after falling from the back of a cruise ship.

The 46-year-old was alone and 60 miles from shore when she was rescued and taken to hospital. Details of her remarkable survival are still emerging - but what could help you stay alive in a similar situation?

Water temperature

There were several lucky factors in this case which helped the survivor, Kay Longstaff.

Sea survival instructor Simon Jinks says she could have sunk three or four metres beneath the water's surface after the initial fall and was fortunate not to be pulled under the ship.

There can be turbulence in the water next to a cruise liner and "some waves can push you away and some waves can take you in", he said - but it depends on the speed of the ship as well as luck.

She was also probably "winded" by the fall from such a large vessel.

Her second stroke of the luck was the warmth of the water she fell into - estimated to have been about 28-29C, or "a little bit warmer than a swimming pool", says Professor Mike Tipton, an expert on surviving extreme environments.

A person can survive for around one hour in 5C water, two hours in 10C and six hours in 15C - but if the temperature is in the high 20s then it is possible to survive for around 25 hours, he says.

Humans can go into cold water shock if the temperature is too low, which means they lose the ability to control their breathing and can potentially inhale water or drown.

And as their body temperature falls, someone can become tired, confused or disorientated.

If she'd fallen into the sea around Britain, she'd have been in water of between 12C and 15C - cool enough to cause cold water shock.

Try to float

According to this guide on Personal Survival Techniques, external, produced for the Irish sea fisheries board, the best way to slow down the rate at which your body cools is to avoid swimming and instead try to float in the water with your knees raised up to your chest.

The "flat, calm conditions" meant the woman in this case was able to float, swim and "stay pretty much where she fell in", says Prof Tipton.

"She wasn't being battered by waves for the whole of the time. She would have most inevitably had drowned if that had been the case."

Watch BBC reporter Natalie Crockett try out the RNLI floating technique

Clothing and footwear improve a person's buoyancy during their first moments in the water because they trap air, according to the RNLI, external. Floating calmly rather than moving around a lot will help the air stay trapped.

Anything you can do to help you float will improve your chances.

This maritime training school on Australia's Sunshine Coast, external advises anyone who finds themselves stuck in the water to look for something that is floating and hold on to it.

If they do not have a life jacket, they should try to make buoyancy out of clothing - a move familiar to many in the UK from school swimming lessons.

Get found

With the time it's possible to survive in the water limited, it's important to get rescued as soon as possible.

In this case, people on board appear to have noticed the woman was missing and used the ship's CCTV to pinpoint the time of her fall and hence her probable location.

But, as Prof Tipton says, it's still very hard to find someone floating alone at sea - particularly at night. "It's just a really difficult thing to find what essentially is a head in the water."

Be female

Women's high proportion of body fat - typically 10% more than men - can work in their favour.

"They have more subcutaneous fat and that means they are more buoyant because the body's buoyancy comes primarily from the air and fat in the body," Prof Tipton told BBC 5 Live.

The extra fat also helps keep the body warm, which helps when the human body gets tired in the water.

"You can imagine if you have to swim for 10 hours to keep your airway clear of the water, there's a pretty good chance you'd get exhausted," he said.

How do you survive 66 days lost at sea?

Keep your head

In order to survive this kind of ordeal, you also need to be mentally resilient.

According to Survival Psychology by Dr John Leach, during disaster situations, most people will be paralysed into doing nothing to help themselves. Others will panic but some will immediately take active measures to survive.

"I think there is a big psychological aspect," said Professor Tipton. "At the time, hours six, seven, eight and nine it must be a fairly desperate situation to be in."

The British woman was found around one mile from where she fell from the Norwegian Star

In this case, the woman reportedly told a rescuer that she sang overnight to stop her getting cold.

Mr Jinks, whose company, Sea Regs, trains boat skippers and crews, says a person's "will to survive" is crucial. "If you go into a situation and think, 'I'm going to die,' your psychology changes," he said.

Conversely, making a decision to tell yourself "I'm not going to die today" can help your chances.

What about the effect of alcohol?

The RNLI says, external around one in eight coastal deaths in the UK involves alcohol and urges swimmers to avoid going into the water after a drink.

It warns that alcohol can seriously impair judgement, reactions and ability to swim.

But Prof Tipton said in one of his recent studies, volunteers consumed six vodka drinks before going into the water.

And he said alcohol "made absolutely no difference to their physiological responses to immersion".

"What it does do is it makes your decision making a little more difficult. People make bad decisions when they've got alcohol on board."

There is no indication that alcohol was involved in this most recent case.

Famous castaways: Who survived longest at sea?

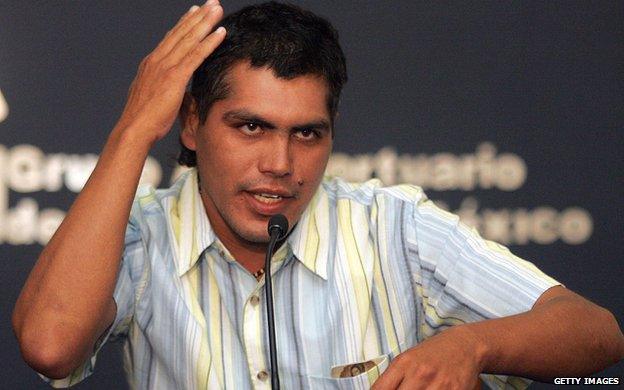

Mexican shark fisherman Jesus Vidana describing his crew's remarkable story of spending 270 days adrift

Jose Salvador Alvarenga, from El Savador, endured 440 days drifting across the Pacific Ocean until he was found in the Marshall Islands in 2013, emaciated and wearing only his underpants, having swum ashore

Poon Lim, a Chinese sailor during World War II, set a record for the longest survival on a life raft. He survived 133 days alone in the Atlantic

In 2006 Mexican shark fisherman Jesus Vidana and his crew spent 270 days adrift in the Pacific Ocean before a Taiwanese tuna fishing vessel rescued them off the Marshall Islands.

US adventurer Steven Callahan survived 76 days in a life raft in the Atlantic in 1982 after a whale rammed into the hull of his sloop, Napoleon Solo.

- Published20 August 2018

- Published4 April 2015

- Published2 May 2017

- Published20 August 2018