Crossing Divides: Police knife crime tactics under scrutiny

- Published

It's 10 minutes into a shift for two officers from the Metropolitan Police's Violent Crime Task Force and an all-too familiar call comes across the radio.

A man has been stabbed at a pizza restaurant in Tottenham, north London.

They speed to the scene to find a crowd of onlookers. Inside, the victim - a young man in his 20s - lies bleeding from a back wound in the restaurant kitchen.

Around him, workers who had called for help carry on taking orders and making dough. A mother arrives, checking it isn't her son who's been hurt.

This twisted version of normality has become almost commonplace, one customer suggests.

"There was stabbing in Wood Green, there was a stabbing down in Tottenham Hale. There are stabbings happening everywhere unfortunately," says one of the officers.

The victim, who is not seriously hurt, refuses to cooperate with police, saying he knows the perpetrators and will deal with the matter himself.

That, too, is not unusual, the police officers explain.

I was patrolling with them as part of the BBC's Crossing Divides season, with the aim of bringing together a senior police officer with a critic of the force's tactics on tackling knife crime.

The officers were among 300 recruited to the task force since it was set up in April last year in response to the rising number of stabbings across London.

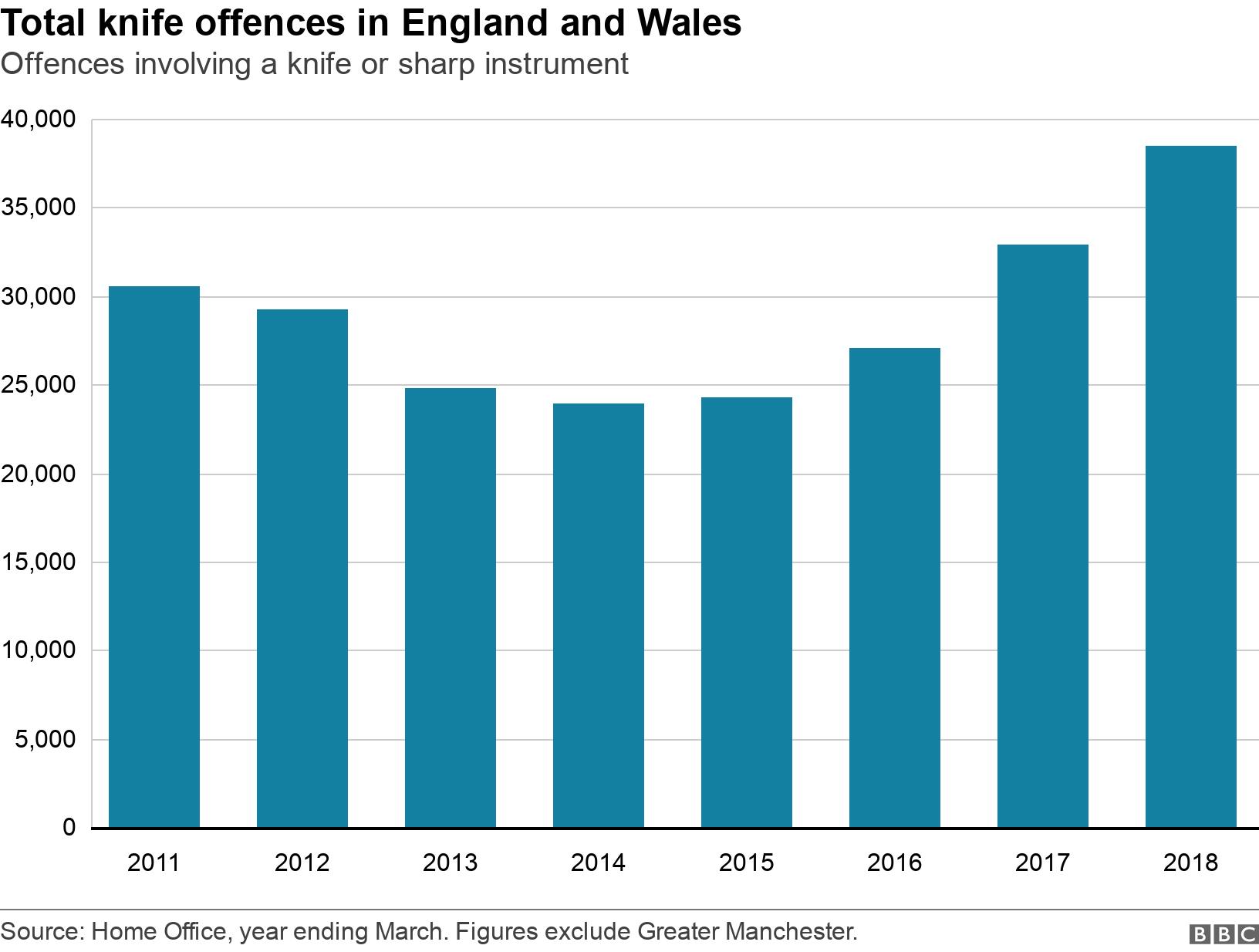

It's a trend matched across England and Wales, with official figures recording 42,957 knife offences in the year to last September.

In the 12 months to March 2018, there were 285 fatal stabbings; the highest since records began more than 70 years ago.

The increase in violent killings over recent years has coincided with a dramatic reduction in police use of stop and search powers, leading several chief constables to speak out.

With London Mayor Sadiq Khan's backing, the Met Police has begun using the tactic more often. It carried out 18,000 searches in January, nearly 7,000 more than the same month two years earlier.

However, the method has proven controversial.

Towards the end of the shift, the task force officers pull over a driver who made a sudden U-turn.

A background check brings up an alert, so they search the car. The driver isn't happy, saying he's been stopped "many times".

"Usually they just have a chat through the window," he says.

"I don't know what these guys' problem was... he's just made up some grounds to search me."

Dijon Joseph, 29, a sports coach and youth mentor from Deptford, south-east London, is another who is unhappy at the police's approach. He says he's been searched as many as 20 times.

Last year, a video of him being handcuffed and forcibly searched by police after officers saw him fist-bump his brother went viral on social media. Police said at the time they were looking for drugs.

"As an upstanding citizen, it's degrading and embarrassing to be stopped on the side of the road and being treated like you are a criminal," he says, suggesting it is a case of "profiling" based on his 6ft 8in frame and ethnicity.

These are the two brothers who went viral after they were arrested for a fist bump.

"I wanted to be a police officer when I was a kid because I genuinely wanted to effect change," he says. Now, he adds, he feels treated like an "enemy".

It's a common complaint. This week, three black community advisers claimed they have been wrongfully searched or arrested by the Met.

The force says 42% of those searched by officers are white, 40% black and 14% Asian.

But how would a senior officer respond when challenged?

The BBC brought together Mr Joseph and Chief Supt Simon Messinger, who heads police in the south London boroughs of Lambeth and Southwark.

Mr Joseph arrives eager with arguments well-prepared. Likewise, the senior officer is keen to get down to business.

Youth mentor Dijon Joseph and Ch Supt Simon Messinger discuss stop and search

But when they meet, the ice is broken immediately as they joke about each other's height outside the cramped police van that was the venue for their meeting.

Mr Joseph doesn't meet many people close to his height, something he believes affects the police's attitude.

"I'm not against stop and search. I'm against when stop and search is misused against citizens like myself based on how I look," he explains.

'Friction point'

Mr Joseph says it has caused a trust issue between the police and community.

"There's always going to be a friction point," Chief Supt Messinger accepts.

"It's a power that we have which isn't well received and it's about the understanding on our side as much as anyone else's."

But he insists the tactic yields results.

According to City Hall, the task force made 1,361 arrests in its first six months, recovering 340 knives.

"Stop and search is the short-term solution," he says.

Even so, Mr Joseph feels officers ought to be better trained in cultural differences and should better engage youths.

The meeting ends with a handshake and a promise to stay in touch, but both men know there is a long road ahead to solving the problem of knife crime.

"We are not going to fix it now or next year," says the police officer.

BBC Crossing Divides

A season of stories about bringing people together in a fragmented world.

- Published8 March 2019

- Published18 July 2019

- Published8 November 2018