Anger at rape victims being asked to hand phones to police

- Published

There has been strong criticism of a move to get rape victims to hand over their phones to police - or risk prosecutions not going ahead.

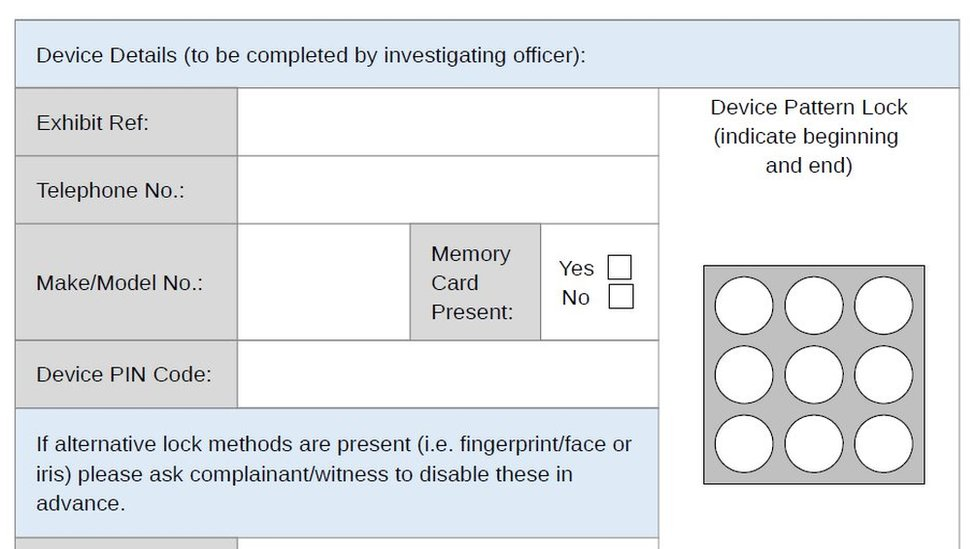

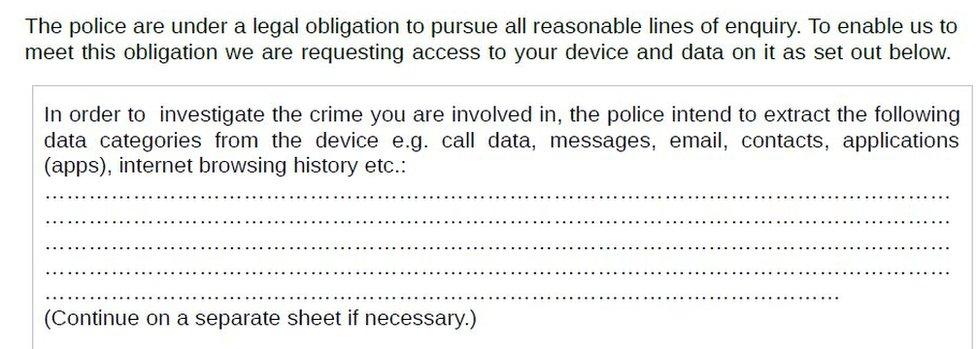

Consent forms asking for permission to access information including emails, messages and photographs are being rolled out across England and Wales.

Prosecutors say the forms make clear investigators should not go beyond "reasonable lines of enquiry".

But Labour's Yvette Cooper said there were "no safeguards in place at all".

The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) said the new consent forms were not a change in policy but were intended to "achieve consistency nationally".

The forms - which can be used for complainants in any criminal investigations - say victims will be able to explain why they don't want to give police access to their data.

But they are also told if they refuse permission "then it may not be possible for the investigation or prosecution to continue".

Ms Cooper, chairwoman of the Commons Home Affairs Select Committee, said the checks and balances to prevent inquiries being inappropriate "were already not working".

She said that for a rape victim, it seemed as if police would be able to look into "every aspect of your life - that any of this information could be given to the person who raped you".

Campaigners for victims' rights and civil liberties said having to share personal information, which could include unrelated sexual history, could stop victims coming forward.

Sarah Green, from End Violence Against Women Coalition, said the implications of handing over a phone were "huge" as many people relied on them for work and they wouldn't be offered a replacement by police.

'My phone was taken for two years'

One woman, who wants to remain anonymous, says she was raped in April 2016 by someone she knew and reported it two months later.

"I was willing to give the police everything they needed. I'd texted people that night about the incident. The police said they wanted to extract data from my phone.

"I was required to hand in my phone and it was only returned to me after repeated requests after two years.

"When I got my phone back, I saw that it had not even been turned on in two years.

"They didn't even take the phone off the perpetrator. I gave his name and address. He's not had to face any consequences."

'I didn't hand over my phone'

Another woman, Leah, was sexually assaulted on a university campus in London last summer.

"A policewoman called to organise an interview and told me she'd need my phone. I didn't see the need to hand it over.

"The whole thing was very stressful and adding stress to what had already happened to me. I didn't think it was relevant.

"When I turned up at the interview and didn't hand over the phone, I was made to feel that I'd done something wrong. It felt so invasive.

"It was almost as traumatic as the incident itself."

Prime Minister Theresa May's spokesman said the issue was complex but police understood the need to balance a respect for privacy with the need to pursue "all reasonable lines of inquiry".

The introduction of consent forms is part of the response to the disclosure scandal, which rocked confidence in the criminal justice system.

Several court cases of rape and serious sexual assault cases collapsed when crucial evidence emerged at the last minute, prompting concerns evidence was not being disclosed early enough.

One of the defendants affected was student Liam Allan, 22 at the time, who had charges dropped when critical material emerged while he was on trial.

Liam Allan talks about what it is like being falsely accused of rape

Police and prosecutors say they are now trying to plug a gap in the law which says complainants and witnesses cannot be forced to disclose relevant content from phones or other devices.

Director of Public Prosecutions Max Hill said such digital information would only be looked at where it forms a "reasonable" line of inquiry, with stringent rules so that only relevant material would go before a court.

A screenshot of part of a consent form for "digital device extraction", provided by the National Police Chiefs Council

However, Labour MP Harriet Harman shared an email she received from a young woman in her constituency, who was raped by a stranger and had all the contents of her phone examined going back five years.

She said: "The danger with this is that in trying to comply with the disclosure rules, they've gone completely over the top."

But Conservative MP Michael Fabricant said those falsely accused of rape were also victims and cited a friend of his who managed to prove his innocence using mobile phone evidence.

He said: "Justice has to be done and that includes those people who have been accused of rape when in fact they are innocent."

'Digital strip-searches'

Civil liberties charity Big Brother Watch said victims should not have to "choose between their privacy and justice".

"The CPS is insisting on digital strip-searches of victims that are unnecessary and violate their rights," the organisation added.

Silkie Carlo, of Big Brother Watch, says victims are being deterred from reporting crimes

Its director Silkie Carlo, told the Victoria Derbyshire programme the organisation had seen instances of police investigating a "stranger rape" requesting years of data from victims, including access to their cloud storage and social media accounts.

She said it was deterring some victims from reporting rapes, potentially leaving dangerous offenders at large.

The Centre for Women's Justice is already planning a legal challenge, supporting at least two women it says have been told their cases could collapse if they do not co-operate with requests for personal data.

Harriet Wistrich, director of the charity, said most complainants understood why they needed to disclose any communication they had with the defendant, but not why their past sexual history would be relevant.

She said: "Given the amount of personal and often very intimate data stored on such devices, particularly by young women, it is not surprising that many victims who are reporting a deeply violating offence do not wish to be further exposed."

- Published27 May 2022

- Published13 November 2018

- Published20 July 2018

- Published30 April 2018

- Published29 April 2018

- Published24 January 2018

- Published27 January 2018

- Published18 January 2018