EU migration to UK 'underestimated' by ONS

- Published

The level of migration from the EU to the UK has been underestimated by the Office for National Statistics from the mid-2000s to 2016.

The ONS said the error affected the number of migrants from eight of the countries which joined the EU in 2004, including Poland.

It said it may have also overstated migration from non-EU countries.

As a result, the status of the immigration figures compiled by the ONS has been downgraded to "experimental".

Immigration experts at the University of Oxford said the latest ONS analysis showed official data has been "systematically underestimating net migration from EU countries".

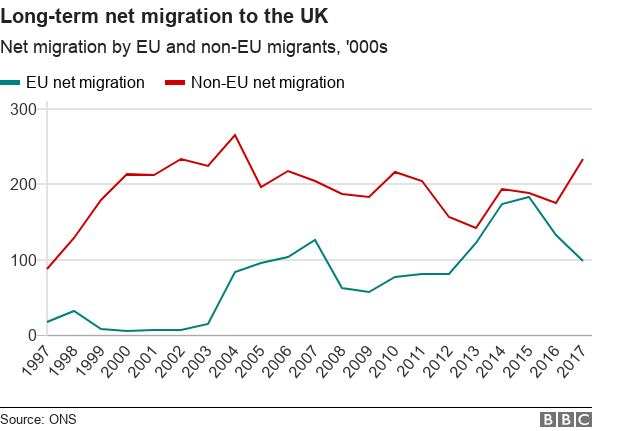

The ONS said new analysis, external showed that in 2015-16, EU net migration - the difference between people arriving and leaving - was 16% higher (29,000) than first thought.

This means an increase in the estimate of EU migration from 178,000 to 207,000 for the year ending March 2016.

Net migration from outside the EU was 13% (25,000) lower, because more foreign students left than previously estimated.

What is the government's migration policy?

The goal of cutting net migration to less than 100,000 a year was introduced by then-Prime Minister David Cameron.

It continued to be a promise in the Conservative manifesto in the 2017 election, with Theresa May wanting to bring net migration down to the "tens of thousands".

But the government never came close to meeting the target and faced repeated calls to drop it.

When draft proposals for a new immigration system were published, the target of 100,000 was left out.

Unveiling the new rules, Sajid Javid - who was then home secretary - said while there was no "specific target" for reducing numbers coming to the UK, net migration would come down to "sustainable levels".

How are immigration statistics compiled?

At the heart of the ONS' migration updates - which are published every three months - is the International Passenger Survey.

The survey was launched in 1961 to help the government better understand how travel and tourism was affecting the economy.

But later, and once Mr Cameron had set a net migration target, the survey became a useful way to estimate who was coming and going for broader political purposes.

For 362 days a year, IPS staff approach travellers at 19 airports, eight ports and the Channel Tunnel rail link.

They ask them where they're from, why they are in the UK and how long they might be staying.

Every year, they survey 800,000 people. Around 250,000 of these results are used to form an estimate for the people either arriving to live in the UK or leaving the UK for at least a year.

However, the IPS does not cover all ports, all of the time, and the sample works out at just over 1% of Heathrow's annual traffic of 78 million people.

The system has faced criticism, with two parliamentary committees concluding the International Passenger Survey is now next to useless on its own for government purposes.

Why does the ONS error matter?

Madeleine Sumption, director of the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford, said its monitoring of net migration figures had shown "for a while that something wasn't quite right".

She said: "This matters because for the past nine years the UK policy debate has been fixated on a single data source, which couldn't bear the load that it was forced to carry.

"Whether the question is how to meet the net migration target or what to do about international students, the truth is that the data were simply not robust enough to be picked apart in such detail."

The admission by the ONS - 24 hours before the latest immigration statistics are published - that its figures have been wrong for over a decade is acutely embarrassing for a body which prides itself on accuracy and reliability.

It adds to growing doubts from a number of experts about the methods it has been using, while the decision to downgrade the status of its figures to "experimental" - which is a kind-of kitemark - raises serious questions about whether future immigration statistics can be trusted.

The regulator says there's "significant uncertainty" about the estimates since 2016, the year of the EU referendum.

That's partly because EU citizens arriving in the UK, who are interviewed for the passenger survey on which the figures are based, may themselves be unclear as to whether or not they'll stay in Britain for at least 12 months, the cut-off point for inclusion in the immigration data.

The ONS said its research showed no single source of data "can fully reflect the complexity of migration" but looking at all available sources provided "a much clearer picture".

"Whilst we go through this transformation journey, we have sought to re-classify our migration statistics as 'experimental statistics' in line with Office for Statistics regulation guidance," it added.

BBC home affairs correspondent Dominic Casciani said the errors in the methodology "broadly cancel each other out".

In February this year, the ONS' update reported that net migration to the UK from countries outside the EU had reached its highest level for 15 years.

Before ONS admitted an error: Statistics on net migration between 1997 and 2017

- Published28 February 2019

- Published23 August 2018