The five major challenges facing electric vehicles

- Published

Encouraging more people into electric vehicles is at the heart of the government's efforts to tackle climate change.

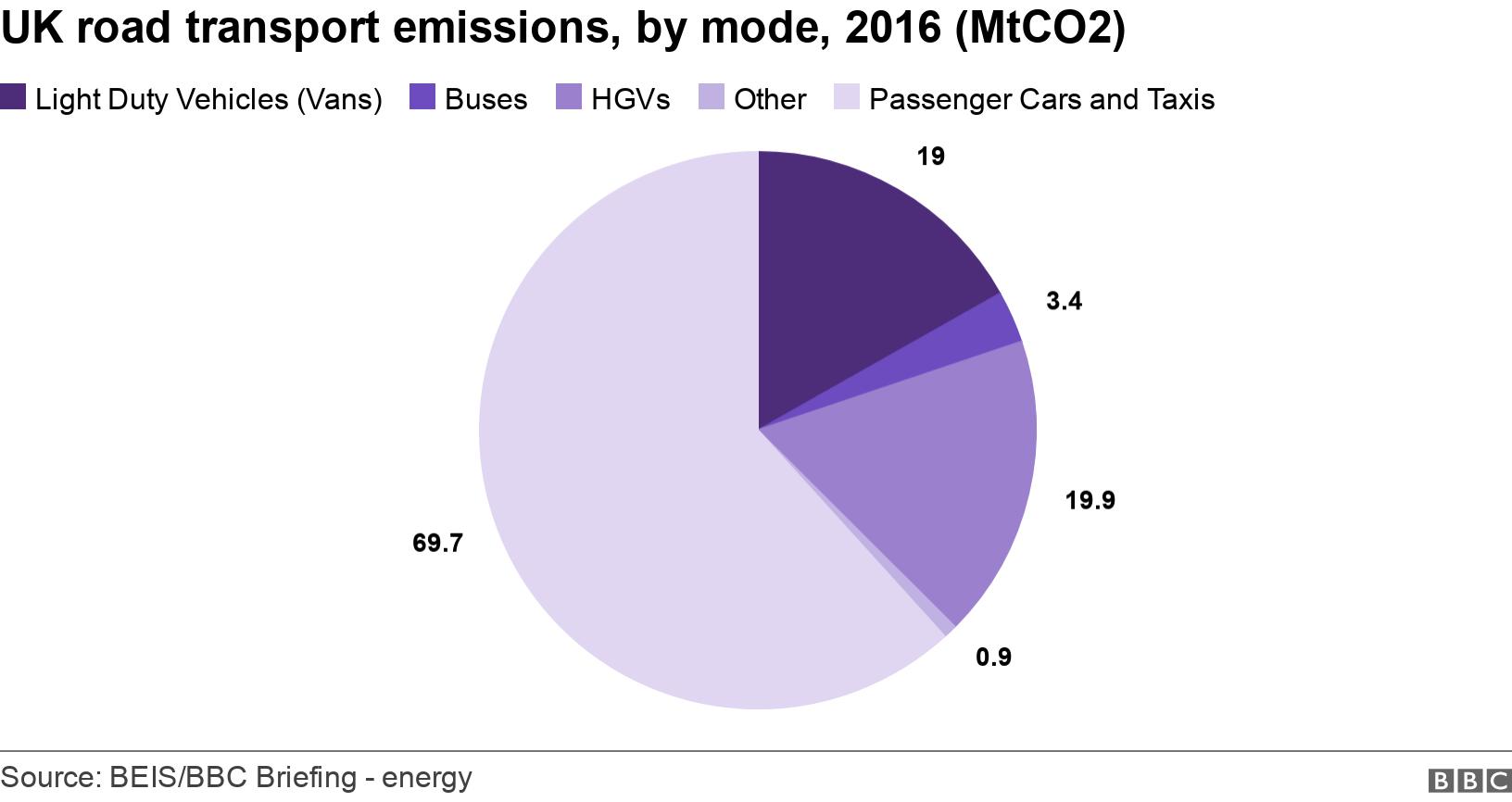

That's because transport accounts for 23% of the UK's CO2 emissions, external - more than any other sector.

Sales of all-electric vehicles are up 70% on last year, leading to suggestions that we have reached a turning point. But there are good reasons to remain cautious.

1. Change takes time

One of the UK's best-selling cars is the all-electric Tesla Model 3. But its success doesn't change the fact that only about 1.1% of new cars, external sold this year are electric, and that the market for used electric vehicles hardly exists.

As it takes most UK drivers anywhere between one and 15 years to change their vehicles, many of us won't be thinking about buying an electric model any time soon.

Bigger changes are needed. We will need many more places for charging electric vehicles, for example. And because fuel tax is an important source of income for the government - and electric vehicle users pay lower taxes - changes to the tax system may be required.

Individuals and businesses also need to be convinced that electric vehicles suit their needs. This is perhaps the hardest part.

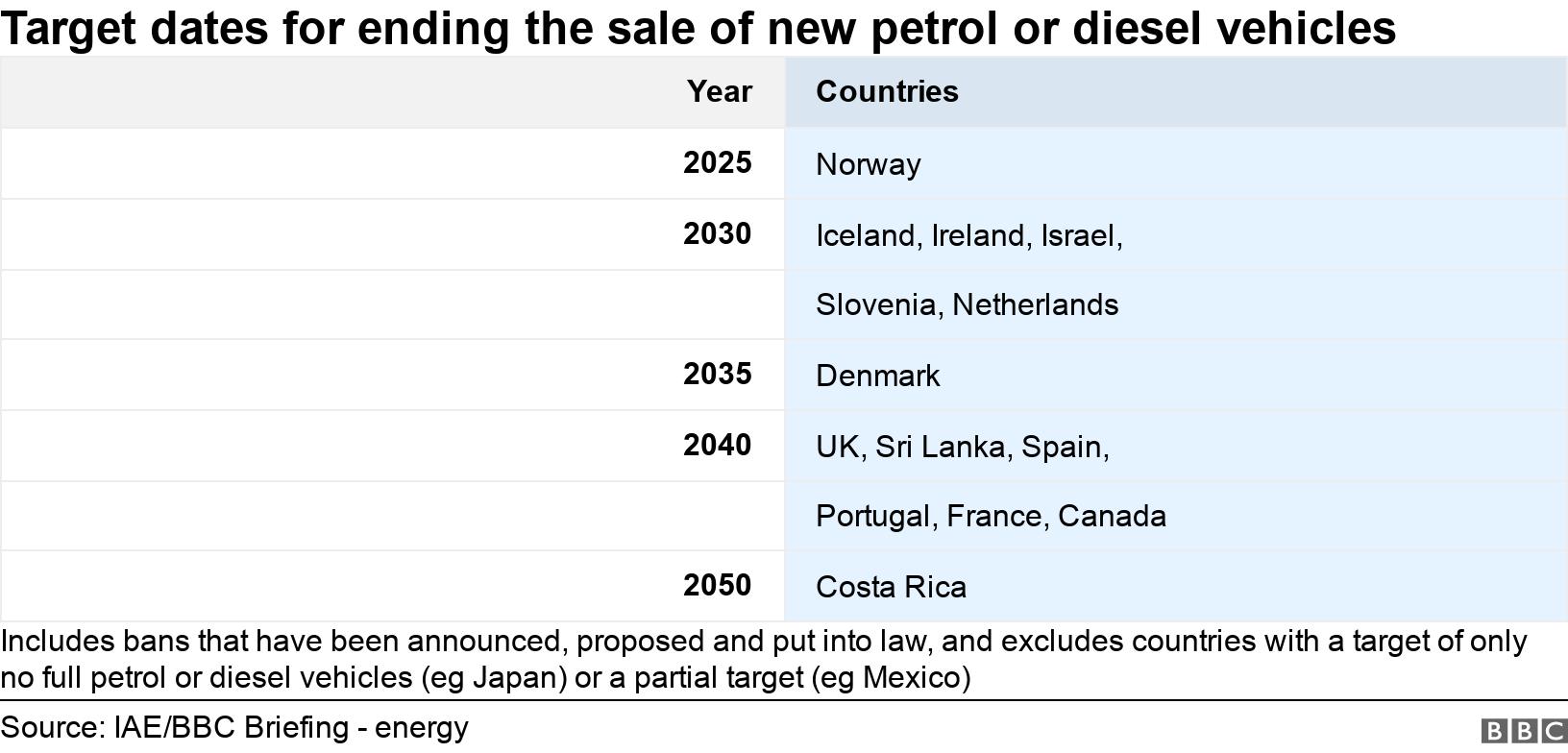

The government aims to ban the sale of new petrol and diesel cars in 2040, a target criticised by MPs who want the change made by 2030.

But even if these goals are met, it is likely to be decades before the most common vehicles on our roads are electric ones.

2. Limited choice

The number of vans on the UK's roads is increasing faster than any other type of vehicle, in part because of the rapid growth in online shopping

Small e-vans are already available and the choice on offer is only likely to increase.

It is difficult to compare prices for diesel and e-vans. However, it can be significantly more expensive to lease an electric version of a popular van, than a diesel one. This is likely to mean that electric vans remain unaffordable for many small firms and self-employed delivery drivers for some time.

There is more choice for those looking for a new car, but electric vehicles are disproportionately aimed at the higher end of the market. Few all-electric models are available for less than £20,000, and buying a new Tesla Model 3 costs about £37,000.

Prices are likely to continue to fall and operating an electric vehicle tends to be cheaper than a petrol or diesel equivalent. But the higher upfront costs may stop many drivers from buying electric vehicles for the foreseeable future, even when a vibrant second-hand market emerges.

3. Backing the right technology

There are rapid developments in battery and charging technology, but this is causing deep uncertainty. Which charging technologies will become the gold standard?

This is a particular problem for people living in apartment blocks, or houses without a private parking space. Should they expect charging to be available at bollards or lamp posts along their street?

Perhaps home charging will not be as important as it is now. Should drivers use facilities at petrol stations, their office or in empty supermarket car parks at night?

Other options being explored include induction pads embedded in major roads, which charge cars as they drive over them.

BBC Briefing is a mini-series of downloadable guides to the big issues in the news, with input from academics, researchers and journalists. It is the BBC's response to audiences demanding better explanation of the facts behind the headlines.

This uncertainty about which approach will become most common slows down private sector investment in charging infrastructure. It also makes the role of local authorities more difficult.

Acting too soon could mean betting on the wrong horse. Waiting too long could encourage more people into hybrid vehicles, which are less dependent on charging infrastructure, but still use fossil fuels.

4. Who will pay?

Even when a standard design for charging emerges, the age-old question of who will pay for installing it remains.

It is widely assumed that the private sector will build, operate and maintain charging infrastructure in the UK.

But businesses have long been slow to get involved, in part because profit margins remain small and government has heavily subsidised the development of charging points. This is slowly changing: BP and Shell have taken over market leaders Chargemaster and Newmotion, and Tesla is actively rolling out its own charging network at motorway service stations.

Yet the question remains: how large should the government's contribution be in future infrastructure development?

If getting people into electric vehicles is for the public good, should local government pay for charging points in areas where demand is too low to offer healthy profits?

And how should investment compare with that in social care, libraries or safe cycling routes, especially when local authority budgets remain as tight as they currently are?

5. The zero-carbon fantasy

Even 100% electric vehicles are not a zero-carbon solution.

They may not produce the usual exhaust pipe emissions, but even if all of the UK's electricity was from renewable sources, there would still be an environmental cost.

Sourcing the minerals used for batteries, dismantling batteries which have deteriorated, and building and delivering vehicles to customers worldwide all involve substantial CO2 emissions. It is impossible to break all of the links.

Electric vehicles are a crucial part of the UK's attempts to drastically reduce transport's emissions. Yet they are no panacea.

A large shift away from motorised vehicles is the only way to fundamentally reduce transport's contribution to climate change, however hard and politically unpalatable that may be.

Read more reports inspired by the BBC Briefing on energy.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Tim Schwanen is a professor of transport studies and geography. He is director of the Transport Studies Unit at the University of Oxford.

You can follow him on Twitter here, external.

Edited by Duncan Walker

- Published10 July 2019

- Published5 July 2019

- Published18 November 2020

- Published13 August 2019