Mugabe's death: UK Zimbabweans on the 'good leader' who 'turned'

- Published

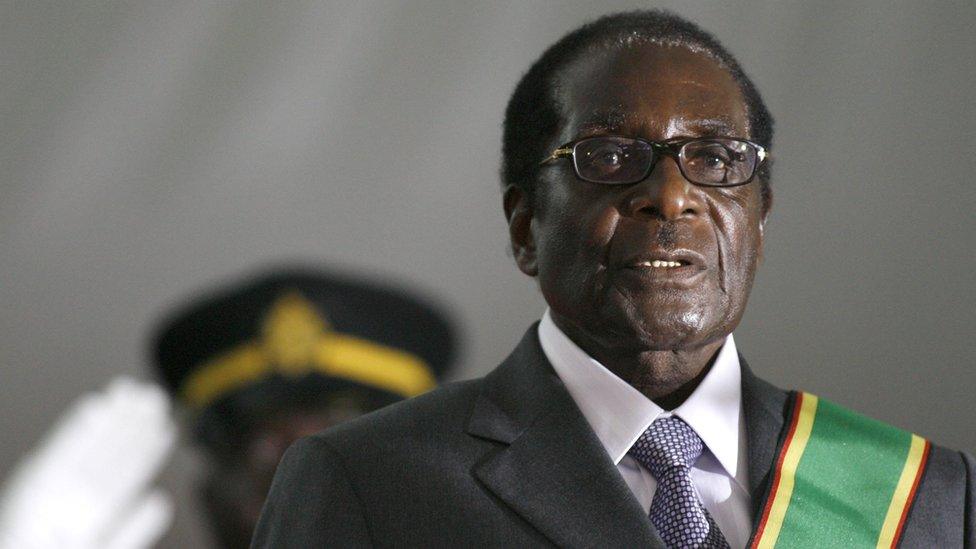

Zimbabweans in the UK are reacting to the death of former president Robert Mugabe, who has died aged 95.

A hero of the former British colony's struggle for freedom, Mr Mugabe became president of newly-independent Zimbabwe when it secured secured independence in 1980 and remained at its helm for a further 37 years.

But his rule turned authoritarian and was marred by controversy, allegations of electoral fraud and intimidation, and deteriorating economic conditions.

He was finally ousted from power in 2017

Around 124,000 people living in the UK last year were born in Zimbabwe, according to the Office for National Statistics, external.

Some came to the UK to work or study. Others fled from abuse and political intimidation under Mr Mugabe.

His death has provoked mixed feelings among those in the UK - some of who have been speaking to the BBC about how they will remember him.

'A sour taste'

Tabetha Darmon was born in Rhodesia in the 1960s. She moved to the UK in 1988 - eight years after the country gained independence from Britain and was internationally recognised as Zimbabwe - and intended to return home. But during the 1990s, she says, the country changed drastically.

"The economy went down, healthcare collapsed," she adds.

"Nobody intervened. Mugabe then turned into a dictator. He forgot the people that he fought for."

Had he died 30 years ago, she would have mourned his death, but she says: "But he's lived until 95. Our children and grandkids in Zimbabwe won't see 50."

Six of Ms Darmon's family members who remained in Zimbabwe died as a result of poor healthcare and no access to HIV treatment, leaving her 19 child relatives to provide for.

"I have to try and balance my life here and provide for those people at home," she says.

"His legacy now with his death has left such a sour taste in my mouth."

'He turned'

Among the former president's most controversial actions was the seizure of land from thousands of white farmers between 2000 and 2001 under a government programme of land reform.

Veronica and David Madgen ran one of the largest farms in Zimbabwe, but fled to the UK in 2001 after it was taken over by Mr Mugabe's supporters.

"The tractors [were] being burnt, the motorcycles [were] being burnt, stones [were being] thrown through the window… it was very difficult to actually come to terms with what was happening," Mrs Madgen says, speaking on BBC Breakfast.

"As a result of the economy going into decline, my husband did a forecast and he said to me, 'We're not going to be able to survive here.' The farm was slowly being carved into pieces."

Despite this, Mrs Madgen says she is "sad for him and his family".

"For the first 20 years that he governed that country, he was a good leader, his wife, Sally, beside him, and his mother. He was a very good leader, until that threat of losing that election got hold of him and he turned."

'Tyrant'

Regis Manyanya spoke to the BBC in 2017 after Robert Mugabe stepped down.

Regis Manyana says he fled Zimbabwe for fear of his life in 1999. He settled in Nottingham, which is twinned with Zimbabwe's capital Harare.

Now chairman of the Nottingham Zimbabwean Community Network, he describes Mr Mugabe as a "tyrant" who "ruled with an iron fist", and says Zimbabweans are still yearning for "a day of total freedom".

"He stole election after election, he was forced into resigning by the military who brought in an equally ruthless man," he says, referring to Emmerson Mnangagwa, who had been Mr Mugabe's deputy before replacing him when he stepped down in 2017.

"Now, as some mourn and some celebrate, we await to see whether his right-hand man [of] 52 years will be attending his funeral."

'Apathy'

Pelagia Nyamayaro, 26, moved to the UK from Bulawayo, a city in south-west Zimbabwe, in 2004. Her mother had been headhunted for a job in the NHS.

She remembers being taught as a child at school in Zimbabwe that the Mugabe government had fought for the liberation of the country, liberating black Zimbabweans from oppression.

It is still hard for her to divorce herself from what she was taught. But on hearing the news of Mugabe's death, she felt apathy.

"I don't really know what to feel, because on the one hand, he's considered as one of the primary figures of Zimbabwe's liberation. On the other hand, we see him and we think, 'wow, I don't really have anything to go back to in Zimbabwe'," she says.

"The way that the country is, it's just very hard to feel very proud, to say that you come from there."

She points out that the economic problems in Zimbabwe "run deep", and are bigger than Mr Mugabe.

"People's lives haven't changed. Whether Mugabe was alive or dead, they're still facing 72 hours without electricity. They probably cannot even contemplate whether they might be alive in five minutes, yet this guy had 95 years of life," she says.

"In truth, people are actually just trying to survive."

Gay rights campaigner Peter Tatchell: "Mugabe became a tyrant"

'A contested legacy'

Dr Knox Chitiyo, an associate fellow at Chatham House and president of the Britain Zimbabwe Society, moved to the UK in 2005 to study.

He frequently returns to Zimbabwe, not only for work, but also to see his mother and sister.

"I'm from the generation who was actually there, I was there at independence at Rufaro Stadium in 1980 when independence happened," he says, noting that younger Zimbabweans are likely to be more critical.

He says that Mugabe's first government was inclusive, and made significant achievements in education and healthcare in the 1980s and 1990s.

"And he did bring a sense of worth for Africans which cannot be underestimated. When you compare with how we were treated in Rhodesia [to] what came afterwards, certainly that sense of identity and African worth, I think, cannot be understated," he says.

However, for Dr Chitiyo, the positives must be balanced against human rights violations, such as the massacres carried out in Matabeleland by the National Army in the 1980s. Thousands were killed and many were tortured.

The declining economy, too, he says, will have a lasting affect on his legacy.

"I don't think there is any Zimbabwean who can say that the declining economy in the 2000s had no impact."

Mugabe was a "hugely influential" figure and leaves behind a "mixed legacy of both achievement and failure", he says.

"[His] legacy doesn't just end now because he's died. It's still a contested legacy both in Zimbabwe and abroad."

- Published6 September 2019

- Published6 September 2019

- Published6 September 2019

- Published6 September 2019

- Published20 March 2019