Robert Mugabe, Zimbabwe's strongman ex-president, dies aged 95

- Published

Zimbabwean and global reaction to Mugabe's death

Robert Mugabe, the Zimbabwean independence icon turned authoritarian leader, has died aged 95.

Mr Mugabe had been receiving treatment in a hospital in Singapore since April. He was ousted in a military coup in 2017 after 37 years in power.

The former president was praised for broadening access to health and education for the black majority.

But later years were marked by violent repression of his political opponents and Zimbabwe's economic ruin.

His successor, Emmerson Mnangagwa, expressed his "utmost sadness", calling Mr Mugabe "an icon of liberation".

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Mr Mnangagwa had been Mr Mugabe's deputy before replacing him.

Singapore's foreign ministry said it was working with the Zimbabwean embassy there to have Mr Mugabe's body flown back to his home country.

Who was Robert Mugabe?

He was born on 21 February 1924 in what was then Rhodesia - a British colony, run by its white minority.

After criticising the government of Rhodesia in 1964 he was imprisoned for more than a decade without trial.

In 1973, while still in prison, he was chosen as president of the Zimbabwe African National Union (Zanu), of which he was a founding member.

Mr Mugabe ruled Zimbabwe for 37 years

Once released, he headed to Mozambique, from where he directed guerrilla raids into Rhodesia but he was also seen as a skilled negotiator.

Political agreements to end the crisis resulted in the new independent Republic of Zimbabwe.

With his high profile in the independence movement, Mr Mugabe secured an overwhelming victory in the republic's first election in 1980.

Zimbabwe's week of upheaval that saw Mugabe ousted

But over his decades in power, international perceptions soured. Mr Mugabe assumed the reputation of a "strongman" leader - all-powerful, ruling by threats and violence but with a strong base of support. An increasing number of critics labelled him a dictator.

Shackled to one man

He died far from home, bitter, lonely, and humiliated - an epic life, with the shabbiest of endings.

Robert Mugabe embodied Africa's struggle against colonialism - in all its fury and its failings.

He was a courageous politician, imprisoned for daring to defy white-minority rule.

Mugabe: From war hero to resignation

The country he finally led to independence was one of the continent's most promising, and for years Zimbabwe more or less flourished. But when the economy faltered, Mr Mugabe lost his nerve. He implemented a catastrophic land reform programme. Zimbabwe quickly slid into hyperinflation, isolation, and political chaos.

The security forces kept Mr Mugabe and his party, Zanu-PF, in power - mostly through terror. But eventually even the army turned against him, and pushed him out.

Few nations have ever been so bound, so shackled, to one man. For decades, Mugabe was Zimbabwe: a ruthless, bitter, sometimes charming man - who helped ruin the land he loved.

In 2000, he seized land from white owners, and in 2008, used violent militias to silence his political opponents during an election.

He famously declared that only God could remove him from office.

Mr Mugabe's downfall came after suspicions that his wife Grace might succeed him

He was forced into sharing power in 2009 amid economic collapse, installing rival Morgan Tsvangirai as prime minister.

But in 2017, amid concerns that he was grooming his wife Grace as his successor, the army - his long-time ally - turned against the president and forced him to step down.

What has the reaction been?

Deputy Information Minister Energy Mutodi, of Mr Mugabe's Zanu-PF party, told the BBC the party was "very much saddened" by his death.

"He's a man who believed himself, he's a man who believed in what he did and he is a man who was very assertive in whatever he said. This was a good man," he said.

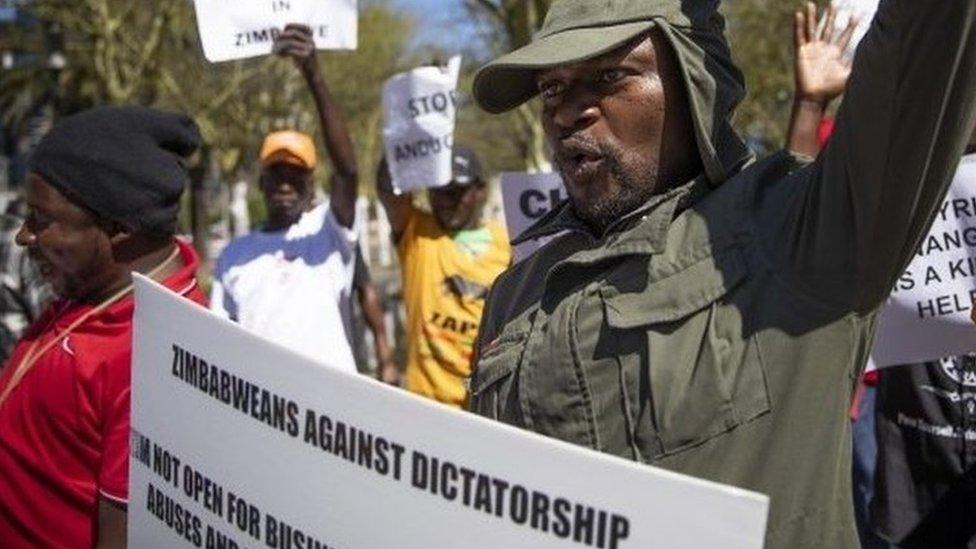

Not everyone agreed, however.

George Walden, one of the British negotiators at the Lancaster House Agreement in 1979 which ended white-minority rule, said Mr Mugabe was a "true monster".

The agreement "turned out rather well... and looked good for a while", but Mr Mugabe later became "a grossly corrupt, vicious dictator", he said.

Zimbabwean Senator David Coltart, once labelled "an enemy of the state" by Mr Mugabe, said his legacy had been marred by his adherence to violence as a political tool.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

"He was always committed to violence, going all the way back to the 1960s... he was no Martin Luther King," he told the BBC World Service. "He never changed in that regard."

But he acknowledged that there was another side to Robert Mugabe, who had "had a great passion for education... [and] mellowed in his later years".

"There's a lot of affection towards him, because we must never forget that he was the person primarily responsible for ending oppressive white minority rule," the senator said.

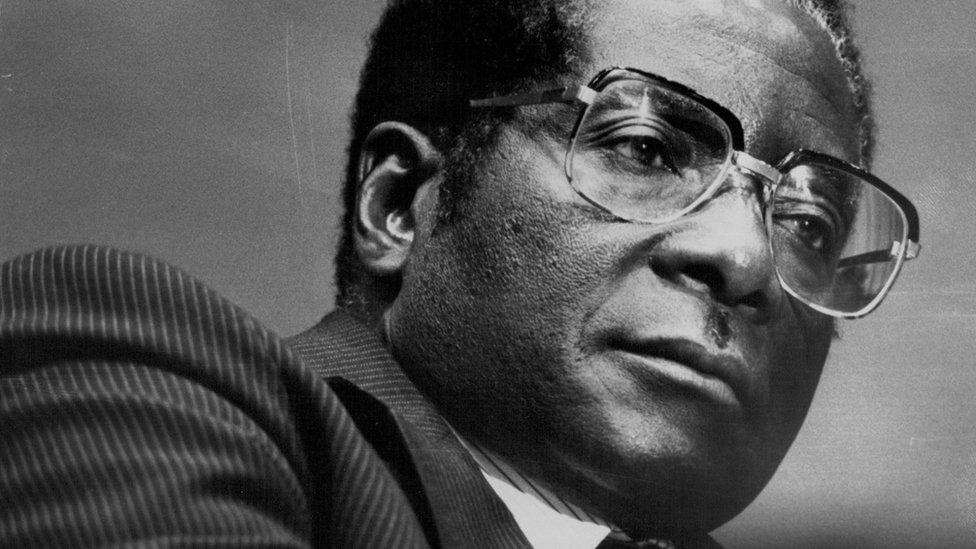

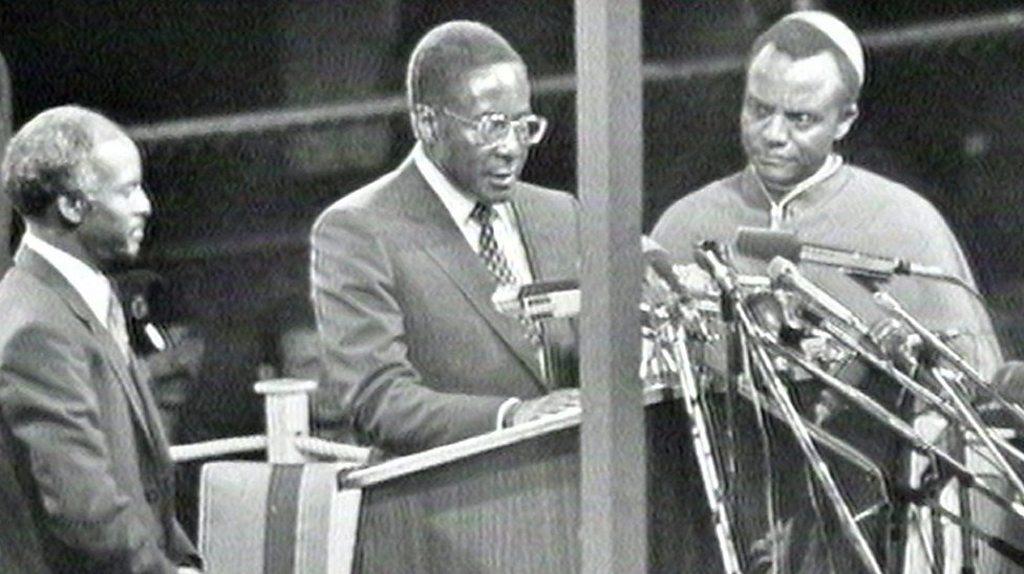

Robert Mugabe in 1981 - just recently named prime minister of an independent Zimbabwe

South Africa's President Cyril Ramaphosa called Mr Mugabe a "champion of Africa's cause against colonialism" who inspired our own struggle against apartheid".

Kenya's President Uhuru Kenyatta said Mr Mugabe had "played a major role in shaping the interests of the African continent" and was "a man of courage who was never afraid to fight for what he believed in even when it was not popular".

Kenya will fly all its flags at half-mast this weekend in honour of Mr Mugabe, he said.

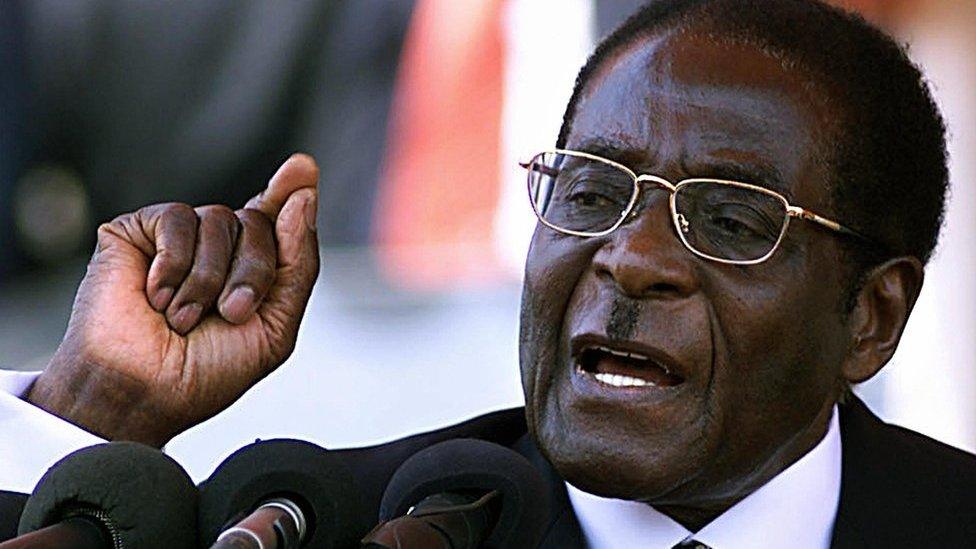

Robert Mugabe was known for his fiery speeches

Veronica Madgen and her husband ran one of the largest farms in Zimbabwe before it was invaded by Mr Mugabe's supporters, forcing the family to come to the UK.

Speaking to the BBC, she recalled: "The tractors [were] being burnt, the motorcycles [were] being burnt, stones [were being] thrown through the window… It was very difficult to actually come to terms with what was happening.

"I was sad for him and his family, because for the first 20 years he governed that country, he was a good leader, until that threat of losing that election got hold of him and he turned."

Yet Mr Mugabe is likely to be remembered for his early achievements, the BBC's Shingai Nyoka reports from the capital, Harare.

In his later years, people called him all sorts of names, but now is probably the time when Zimbabweans will think back to his 37 years in power, she says.

There's a local saying that whoever dies becomes a hero, and we're likely to see that now, our correspondent adds.

Gay rights campaigner Peter Tatchell: "Mugabe became a tyrant"

- Published6 September 2019

- Published6 September 2019

- Published21 November 2017

- Published25 August 2019

- Published21 November 2017

- Published6 September 2019