UK migration: Rise in net migration from outside EU

- Published

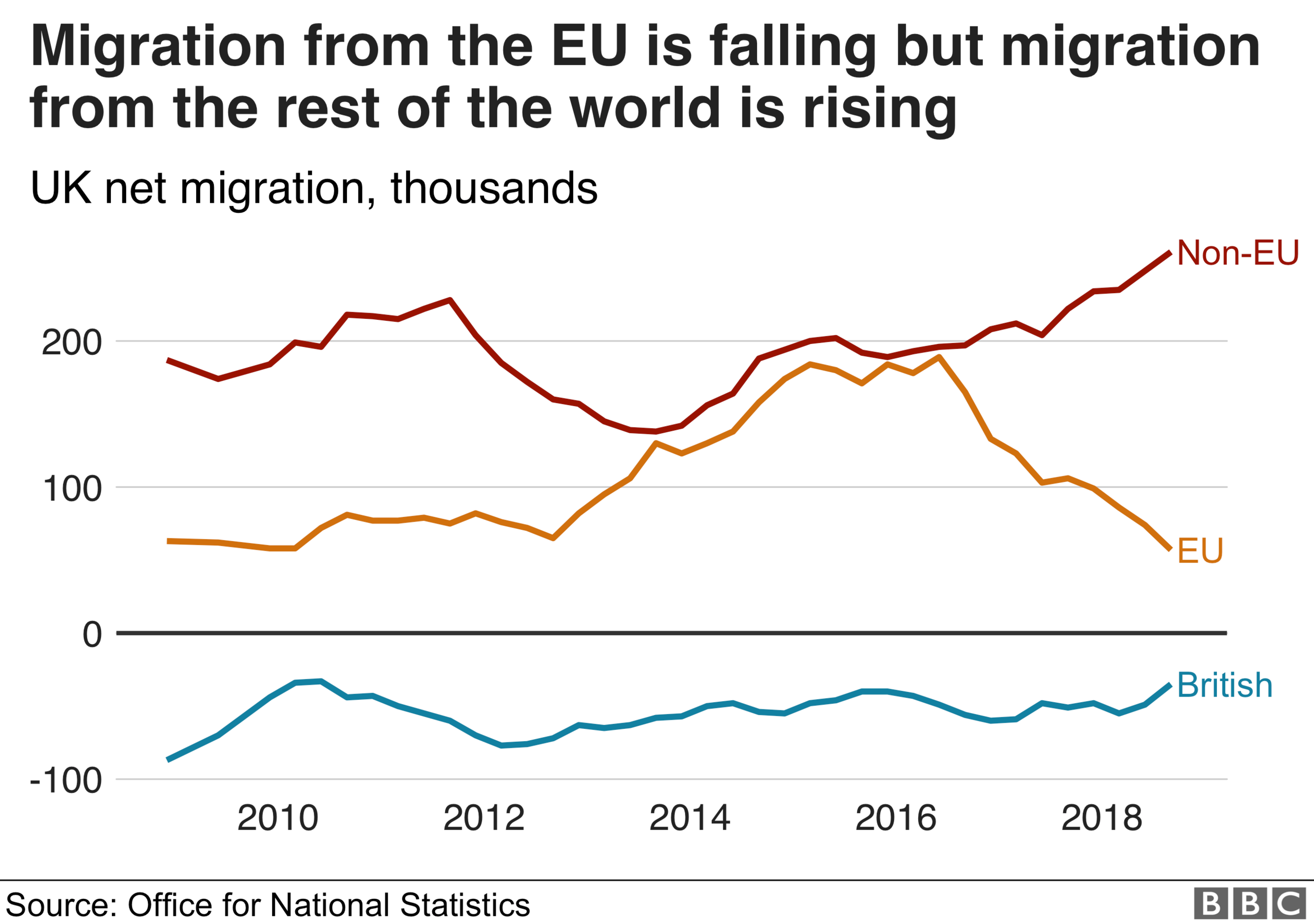

Net migration to the UK from countries outside the European Union has hit its highest level for 15 years, the Office for National Statistics says.

Figures show 261,000 more non-EU citizens came to the UK than left in the year ending September 2018 - the highest since 2004.

In contrast, net migration from EU countries has continued to fall to a level last seen in 2009.

The figures, external are the last set before the UK is due to leave the EU next month.

And separate figures released by the Home Office show the number of EU nationals applying for British citizenship hit an all-time high last year, rising by 23% to about 48,000.

'Complex decision'

In December, the prime minister said the government was sticking to its longstanding ambition to bring net migration down to the "tens of thousands".

The ONS has put net migration in the year to September at 283,000.

It says more than 625,000 people moved to the UK and about 345,000 people left.

Jay Lindop, director of the Centre for International Migration at the ONS, said: "Decisions to migrate are complex and a person's decision to move to or from the UK will always be influenced by a range of factors, including work, study and family reasons.

"Different patterns for EU and non-EU migration have emerged since mid-2016, when the EU referendum vote took place."

Overall, net migration, immigration and emigration figures have remained broadly stable since the end of 2016, the ONS said.

Immigration minister Caroline Nokes said the UK was continuing to attract and retain highly skilled workers, including doctors and nurses, but was "committed to controlled and sustainable migration".

"As we leave the EU, our new immigration system will give us full control over who comes here for the first time in decades, while enabling employers to have access to the skills they need from around the world."

She added that the government had "always been clear" it wanted EU citizens to stay and the EU Settlement Scheme, which allows EU nationals to apply to stay, made that simple.

Analysis

By Danny Shaw, BBC home affairs correspondent

Since the referendum in June 2016 a clear pattern has emerged. Immigration to the UK from the European Union has declined while the number of people coming from outside the bloc has gone up.

It may be that the two trends are not related, but it seems likely that they are.

With fewer EU workers available than before, businesses and the public sector appear to be looking further afield to fill vacancies.

That's reflected in the statistics for those arriving with a "definite job".

The number of EU citizens in that category dropped from 108,000 in the 12 months before the referendum to 70,000 in the year to last September, whereas non-EU migrants coming to Britain with a definite job offer went up from 51,000 to 69,000.

It may be a foretaste of things to come after Brexit, when the government is able to restrict EU migration in a way that hasn't been possible before.

The ONS report also showed:

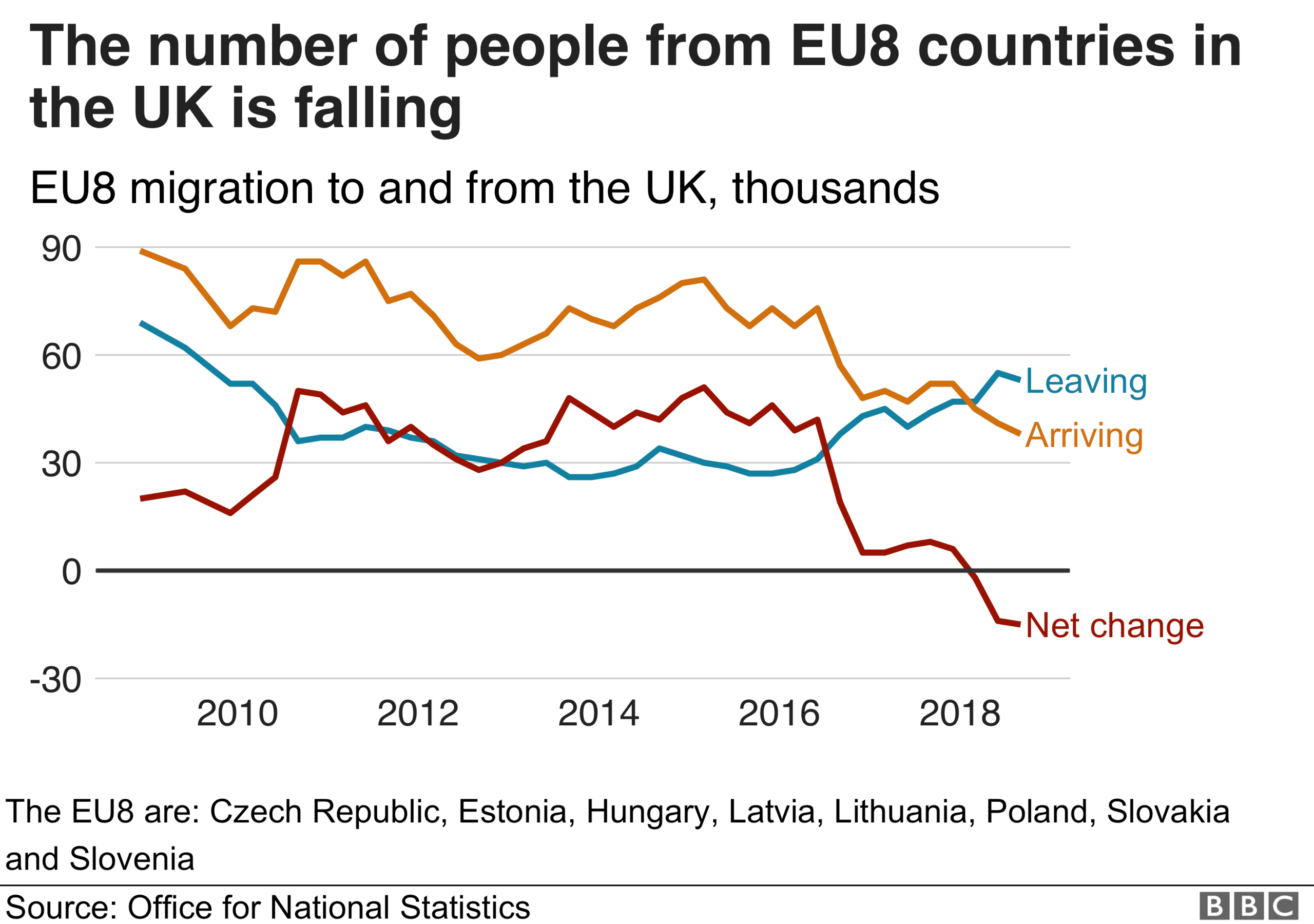

More citizens from Central and Eastern European countries known as the EU8 - which includes Poland, Slovakia and Lithuania - are leaving the UK than arriving. This pattern differs from all other EU countries

The number of people coming to the UK for work has fallen to its lowest level since 2014 - this follows a fall in the number of EU citizens arriving to work

More people are coming to the UK to study, with non-EU student immigration at its highest level since 2011

Madeleine Sumption, from the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford, said the data showed Britain was not as attractive to EU migrants as it was a couple of years ago.

"That may be because of Brexit-related political uncertainty, the falling value of the pound making UK wages less attractive, or simply the fact that job opportunities have improved in other EU countries," she said.

She added that EU net migration happened to be unusually high in the run-up to the referendum, so at least some of the decline would probably have happened even without Brexit.

Diane Abbott, Labour's shadow home secretary, said: "Once again the number of migrants coming here vastly outstrips its unworkable 100,000 net migration target.

"Its policy is not really about reducing numbers but allows it to maintain a constant campaign against migration and migrants."

She criticised the immigration bill currently going through Parliament and accused the home secretary of promising more business access to overseas workers, at the same time as effectively removing all their rights.

Marley Morris, of the Institute for Public Policy Research, a centre-left think tank, said the "marked fall" in EU net migration meant the government needed to "act now to reassure EU citizens and contain the economic damage".

"It must ramp up its communications campaign on settled status, send a strong message to employers that rights must be protected, and clarify its proposals for a no deal scenario."

- Published18 September 2018

- Published19 December 2018

- Published29 November 2018

- Published19 December 2018