UK's 1960s French 'Soviet spy' plot with Sunday Times revealed in memos

- Published

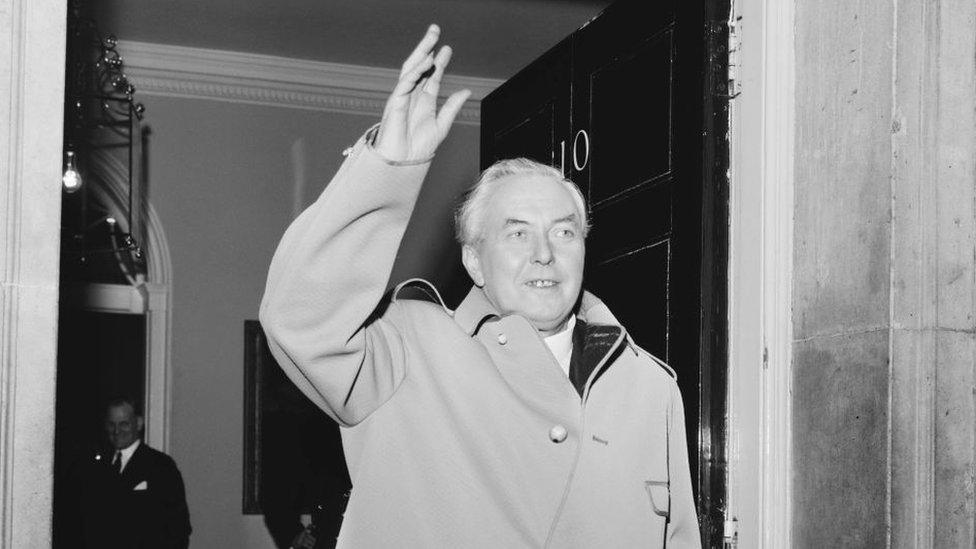

Then-prime minister, Labour's Harold Wilson, knew of the conspiracy with the Sunday Times

The British government conspired with a newspaper in the late 1960s to suggest a Soviet spy had penetrated the highest echelons of the French state.

Newly-released memos show the Foreign Office urged the Sunday Times to suggest France had "its own Kim Philby" - the notorious British double agent.

The plot is revealed in documents from the National Archives.

It was known about at the top of the UK government, including then-prime minister, Labour's Harold Wilson.

The apparent aim was to convince the French to stop the magazine, Paris Match, from publishing Philby's memoirs - and deflect some of the criticism levelled against British intelligence at the time.

There were also fears that Philby's book, written from exile in Moscow where he had defected to in 1963, would contain embarrassing revelations and would be used as propaganda by the KGB.

The plot came at a time of poor Anglo-French relations as President Charles de Gaulle repeatedly stopped the UK joining the European Community.

The revelation is contained in a memo dated 3 January 1968 from Sir Denis Greenhill, one of the most senior officials at the Foreign Office, to Cabinet Secretary Sir Burke Trend, and the Foreign Office minister, Lord Chalfont.

The memo reads: "As agreed, I consulted Lord Chalfont on whether he thought it would be a good idea to suggest to Mr [Harry] Evans [editor] of the Sunday Times that they write an article entitled 'Is there a French Philby?'. Lord Chalfont agreed that this might be profitable.

"I accordingly saw Mr Evans last evening for a few minutes and put the idea to him. I suggested that the article might start from the point that Philby's memoirs seemed likely to appear in Paris Match and then go on to speculate whether the French had escaped the penetration which Philby and company had successfully achieved here… He seemed quite taken with the idea but made no promises."

Double agent Kim Philby, one of Britain's most infamous spies, gave information to the Soviet Union's KGB

In the memo, Sir Denis also suggested the Sunday Times examine a spy novel by Leon Uris called Topaz - about Russian intelligence operations in France - which the diplomat claimed "was founded on fact".

Another memo from Sir Denis dated 16 March 1968 reported on a follow-up exchange with Harry Evans. The Sunday Times editor asked Sir Denis to confirm various pieces of information his reporters had dug up.

Sir Denis replied: "After consulting Lord Chalfont, I rang up Mr Evans and told him that we would not wish to give him any detailed comments but I could tell him that in our view their work was 'a pretty good effort'."

'Dirty work'

A week or so later, on 28 March, Sir Denis reported back to his superiors on yet another conversation.

"Mr Harold Evans spoke to me again today about the Sunday Times piece 'is there a French Philby?'… They proposed to publish it on Sunday 7 April and that Life magazine were also interested in it. He said he would be getting a full text of it next week and would be happy to show it to me."

On a covering note, Lord Chalfont scribbled: "There is no honour in a bit of dirty work at this particular crossroads. I will tell the prime minister."

In mid-April, both the Sunday Times and Life magazine published stories suggesting a Soviet spy was working on President de Gaulle's staff.

The Sunday Times reported: "There has been a traitor, a French Philby, who pushed President de Gaulle into anti-Western acts."

Its reports were based in part on evidence provided by Colonel Philippe de Vosjoli, a former French intelligence officer, who was said to be working for the United States authorities. The claims were dismissed by de Gaulle's office as "ridiculous and grotesque".

French President Charles de Gaulle, pictured in Lyon in 1968, dismissed the Sunday Times reports

There were subsequent reports claiming the Vosjoli allegations were CIA revenge for de Gaulle's purge of US intelligence officers in France.

In a separate memo dated 18 January 1968, Sir Denis Greenhill accused the French of "treachery" when he feared they might agree to publish Philby's memoirs.

"I think we have taken all reasonable steps to impede Philby in this matter and I much regret it if the French have finally agreed to pay him a considerable sum," he wrote.

"However, treachery is more familiar to the French than it is to us and no doubt the publisher was for this reason better able to accommodate himself to the fact that he was liberally rewarding someone who had damaged his own country's interests."

Related topics

- Published4 April 2016

- Published3 March 2013

- Published26 December 2020