Diary reveals birth of secret UK-US spy pact that grew into Five Eyes

- Published

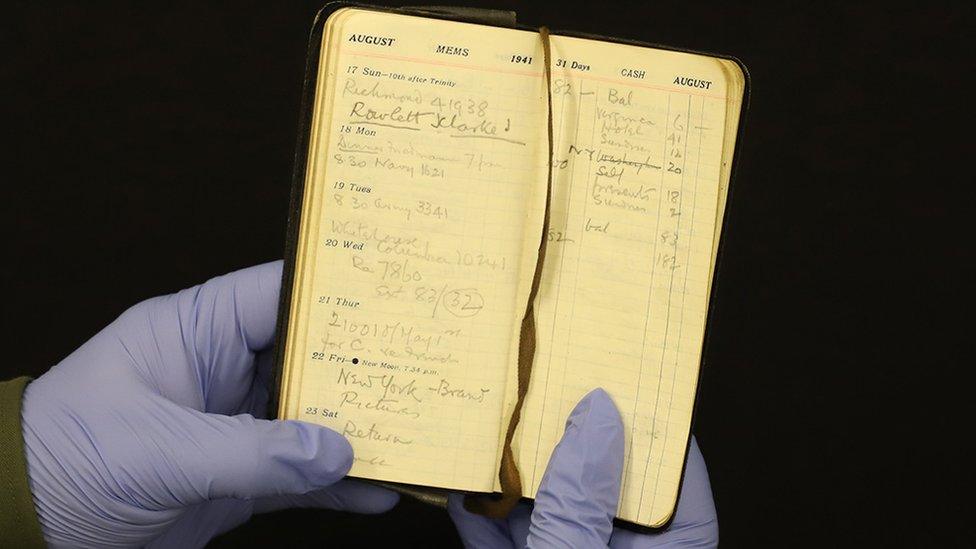

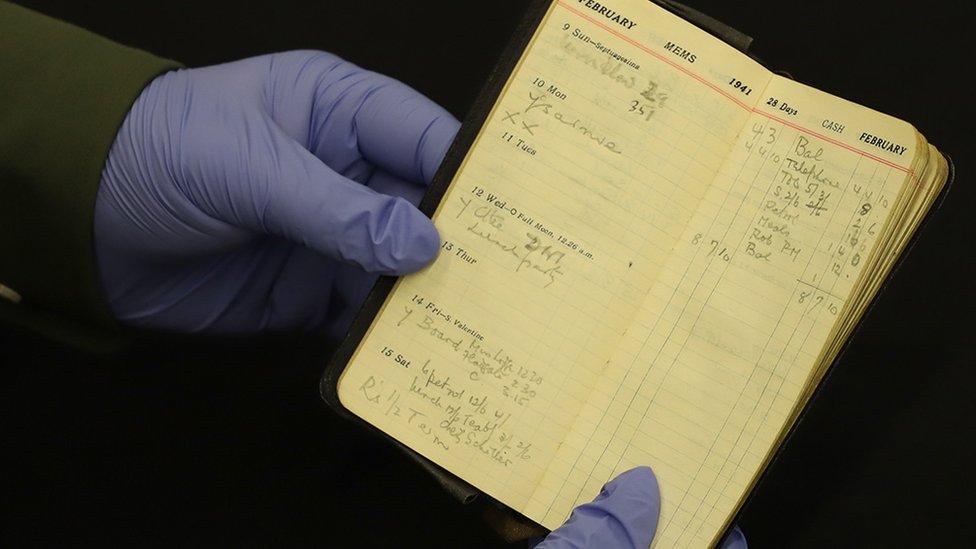

Pages from the diary of Alastair Denniston - the head of Bletchley Park at the time - have been released

New documents have been released about the birth of a secret intelligence pact between the US and UK 75 years ago.

The documents, including diary entries, detail the war time meetings that began at Bletchley Park and led to the UKUSA deal being signed in March 1946.

The alliance involved working together to intercept communications and break codes, sharing almost everything.

It grew into what is today called the "Five Eyes" pact of the UK, US, Australia, New Zealand and Canada.

"Together, we are greater than the sum of our parts," said Jeremy Fleming, director of GCHQ, and director of the US National Security Agency, Gen Paul Nakasone, in a joint statement to mark the anniversary, amid talk of expanding the group even further.

'The Ys are coming!'

A short entry from February 1941 in the diary of Alastair Denniston, released for the first time today by GCHQ, marked the beginning of what was once the most secret of relationships.

"The Ys are coming!" it read - meaning the Yanks.

Denniston was head of Bletchley Park and he was welcoming a group of American code breakers at a time when the US had not yet entered the Second World War.

"There are going to be four Americans who are coming to see me at 12 o'clock tonight. I require you to come in with the sherry. You are not to tell anybody who they are or what they will be doing," he told his assistant.

Another entry from Alastair Denniston's diary from February 1941 reads the "Ys arrive" - meaning Yanks

The Americans had undertaken a perilous crossing with their boat shot at by Nazi planes but they arrived at the home of British code breakers on a mission of huge importance.

With the permission of then-Prime Minister Winston Churchill, the two groups of spies would share their most sensitive secrets - that the UK had broken the German Enigma code and the US the Japanese code called Purple.

Further diary entries reveal how key figures would travel back and forth over the Atlantic, including Denniston to meet with his opposite number as well as code breaker Alan Turing.

The relationship forged in that visit would outlast World War Two and, after a series of meetings, be formalised at the start of the Cold War with a document signed in Washington on 5 March 1946.

The agreement was something of a "marriage contract" - each agreed honesty, openness and commitment to the other including a "no spy agreement" in which they would not target the other side.

They would share nearly all the intelligence they produced through breaking codes and intercepting communications (known as signals intelligence or SIGINT) although the agreement did allow some wiggle room if one side felt they had to act independently.

Initially known as UKUSA, over the next 10 years it would be expanded as Australia, Canada and New Zealand joined, making up what is known today as the Five Eyes alliance. Details of the original deal were secret until 2010.

The power of the alliance in WW2 has made it the heart of what is sometimes called the "special relationship" between the two countries. The term seems increasingly outdated but the one place where it has always been real is when it comes to code breaking.

'Global partnerships are key'

"This alliance defines how we share communication, translation, analysis, and code breaking information, and has helped protect our countries and allies for decades," said Mr Fleming of GCHQ and Gen Nakasone in their joint statement.

"The modern digital world is constantly evolving. Threats don't respect international borders. Global partnerships are key to our security and economic prosperity - and none more so than the one between our two countries."

The relationship meant that the allies divided up the world between them when it came to intercepting communications. In the case of the Cuban Missile Crisis, this meant a GCHQ outstation in Scarborough would end up playing a critical role in delivering intelligence to the desk of President Kennedy in Washington.

From 2016: A look at the intelligence relationship between the US and the UK

The NSA and GCHQ continue to divide up tasks - GCHQ for instance monitors the hackers of Russia's GRU military intelligence agency and passed intelligence to the US when they saw them hacking into the Democratic National Committee during the 2016 US Presidential election.

The relationship remains close with staff from each side travelling over the Atlantic to work in the other side's agency and is far more intimate than that of MI6 and CIA, which deal with human, as opposed to signals intelligence.

But the relationship has not always been smooth. Intimacy creates risks. In the early Cold War, there were fears that the other side might be "leaky".

In Britain this came after revelations about the Cambridge Five showed individuals within British intelligence had betrayed secrets to the Soviet Union. The UK also has worried about showing it was contributing enough, especially given US resources dwarf its own (although expertise in code breaking has often made up for this).

More recently, there was tension after a GCHQ whistleblower, Katharine Gun revealed an NSA memo that showed plans to spy on the UN in the run up to the Iraq War in 2003.

And former NSA contractor Edward Snowden revealed to the world the extent to which the two allies had built a vast capability to intercept global communications with almost no public awareness and little oversight.

Former NSA contractor Edward Snowden revealed much about the close relationship between US and UK intelligence gathering

Other countries have sometimes suggested they wanted in on the deal. Germany made noises about a "no spy deal" in the wake of the Snowden revelations which showed the US spying on it. But Five Eyes is not simply an intelligence sharing alliance but an intelligence production alliance where members are expected to contribute and this appeared to be an obstacle.

Recently, Western intelligence agencies have focused more on China, making Australia's role increasingly important.

The sensitives were also on display when the US warned about limiting intelligence sharing if the UK continued to use Chinese telecoms Huawei in its new 5G network (the UK changed its position in 2020 to exclude the company).

The changing focus has also led to talk about Japan and perhaps others in Asia joining Five Eyes.

Officials say this is unlikely even though they do expect closer co-operation. The reality is that the alliance still remains one rooted in the trust and personal connections first forged during the WW2.

- Published8 February 2016

- Published29 October 2013

- Published20 February 2019