After a 32-year battle for justice, what is Hillsborough's legacy?

- Published

Chrissie Burke, Jenni Hicks, Debbie Matthews and Deanna Matthews

For 32 years the families of victims of the Hillsborough tragedy have been fighting for justice. As the collapse of the last criminal trial this week marks the likely end of the legal road, what will be the legacy of Britain's worst sports disaster?

A nondescript business park on the outskirts of Warrington made an unlikely setting for a victory rally. Avenues of anonymous offices are not the usual backdrop for jubilant scenes of singing and flag-waving. But this was a moment of history for the Hillsborough families, and they were determined to celebrate.

They linked arms as they sang You'll Never Walk Alone, and held up pictures of their loved ones for the world's media to see. The famous Liverpool anthem seemed particularly appropriate. They hadn't walked alone. They'd found joint strength in their common cause. And as they waved their scarves aloft, they sang of having "hope in their hearts". They certainly felt that the tide was turning their way.

Relatives of those who died in the Hillsborough disaster sing You'll Never Walk Alone, Warrington, 2016

That was five years ago, as the second set of Hillsborough inquests came to an end in 2016. The families were celebrating verdicts which they had waited 27 years for. The jury had found that the 96 men, women and children who were killed on the football terraces in 1989 were unlawfully killed. And crucially, that they were not responsible for their own deaths.

Jenni Hicks and Deanna Matthews will never forget that day.

Jenni lost her two daughters Sarah, 19, and Victoria, 15, at Hillsborough. Deanna's uncle Brian was killed on the terraces too.

"It was the verdict we should have had all those years earlier," Jenni says. "I was full of optimism and hope... I felt that now that we've got those verdicts there has to be accountability".

Jenni Hicks

Deanna also felt positive. "I was gobsmacked, I remember sitting in the room and every time we got a verdict I could feel the tension in my chest loosening a little bit," she says.

But Deanna also remembers being warned not to feel too hopeful. "One of the barristers told me, 'You should leave it here, because you're not going to get any more.'

"I thought, 'How can we not get any more? All of our truth is out there for the world to see, everything that we've known, is now proven to everybody as fact.'"

Debbie and Deanna Matthews

It had taken a long string of inquiries and investigations to get to this point. In 2016 I spoke to several of the Hillsborough families to ask them what it felt like to have fought for so long.

They spoke of the years taking their toll. Of having to relive their harrowing experiences, each time new court proceedings began. And of being unable to move on with life, while the judicial process was still grinding along. But the "hope in their hearts" that they'd sung of was their optimism that criminal prosecutions would follow the inquest verdicts.

After all, their loved ones had been unlawfully killed. Damian Kavanagh was one of the Liverpool fans to survive the crush on the terraces. He spoke to me after the inquests and posed the simplest of questions: "This is unlawful killing. So someone's broken the law. So who is it?"

At the inquests, the match commander, former Chief Superintendent David Duckenfield gave evidence accepting that his failure to close the tunnel to the overcrowded terraces was "the direct cause of the deaths of 96 people".

David Duckenfield leaving after giving evidence to the Hillsborough Inquest, Warrington, 2015

This admission in itself was historic. It was also crucial in helping the inquest jurors to reach their unlawful killing verdict. They'd been told that, in order to be satisfied that those who died were unlawfully killed, they had to be sure that Mr Duckenfield had breached the duty of care which he owed the fans, and that this had amounted to gross negligence.

This was the first time there was any accountability for the deaths. But an inquest is not a criminal court. It's a legal process designed to find out the full facts about death without attributing blame. It carries no penalty for anyone whose actions may have contributed to what happened.

It meant that if there was to be full liability, the families would still have some way to travel along their legal journey.

They put their faith in the two criminal investigations which had been set up in the wake of the Hillsborough Independent Panel report, which was published in 2012.

The first investigation, called Operation Resolve cost £65m and led to the prosecution of Mr Duckenfield. But after his first trial ended with a hung jury, a retrial saw him acquitted in 2019. The only conviction was of the Sheffield Wednesday club secretary Graham Mackrell, who was found guilty of a minor health and safety charge.

The second investigation run by the Independent Office for Police Conduct resulted in the prosecution of three men for amending police statements after the disaster. But earlier this week the trial collapsed half-way through.

Deanna Matthews was at the temporary Nightingale court in Salford when the judge ruled that there was no case to answer. Because of the pandemic, the trial was held at the Lowry Theatre. Deanna sat in the upper circle with her mum Debbie, alongside Jenni Hicks and Chrissie Burke, whose father Henry died at Hillsborough.

The four women had been to court together for nearly every day of the trial. Now they supported each other as they were told that the case was being thrown out.

Suddenly they found themselves at the end of the legal road.

Chrissie got to her feet and addressed the court, her voice shaking with emotion. She shouted down at the judge, who was sitting on the stage, and yelled, "The judiciary is broken. The law needs to change. I have got to live the rest of my life knowing my father was buried with a lie."

Chrissie Burke

Deanna remembered the barrister who had told her not to have high expectations, after the inquests in 2016. "Fast-forward a few years, and it turns out that QC was right. We should have stopped then. That is all we were going to get," she told me.

"This does not mean that there wasn't a cover-up. It means that the law we've got today is not fit for purpose."

No-one disputes that police statements were amended after Hillsborough. The trial collapsed because the statements were first prepared for the 1989 public inquiry chaired by Lord Taylor. The judge ruled that because that inquiry wasn't a "court of law" the three defendants could not have perverted the course of justice. Defence barristers said afterwards they believed it proved there was no cover-up after Hillsborough.

But some believe that the prosecution could have been handled differently.

Mike Benbow, who is a former director of the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) Hillsborough investigation, told me that the police watchdog submitted comprehensive files to the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) for consideration before charges were brought. These included other potential offences including misconduct in public office and referred to additional suspects. But the CPS chose to prosecute solely for perverting the course of justice.

After the inquests, lawyers for the families sent the CPS an 86-page document with 595 references to the evidence setting out what the charges should be, and who should be charged. They tell me this was not reflected in the prosecution which was brought.

The CPS said: "Since 2013 we have worked closely with the IOPC to establish whether there was sufficient evidence to bring prosecutions against a number of individuals for offences committed before the day of the match, on the day of the match or in the aftermath. It is crucial that we presented the evidence gathered by the IOPC investigation teams to a court and we have worked tirelessly to prepare the case for the jury to understand this evidence."

So how is it possible for the families to endure a public inquiry, two sets of inquests, four trials, and a string of other reviews and reports, and to emerge feeling angry, let down, and without accountability?

Though the second inquests were successful for the families, the criminal courts were a different matter.

"Something's got to change. A Crown Court isn't the right place for trials of this magnitude," Jenni Hicks says.

The Hillsborough Independent Panel report which was published in 2012 was fundamental in paving the way for the fresh inquests a couple of years later. Prof Phil Scraton, lead author of the report, says that the criminal justice system is not robust enough to cope with a case which has dragged on for so long.

Prof Scraton

"The problem about having long-delayed trials is that there is a passage of time and during that time, justice is delayed. And justice delayed is justice denied. I think that is the real message of all of these cases that take so long to come to trial," he says.

But Prof Scraton believes that the more the families felt they were being let down, the more they forged ahead themselves. He feels that their struggle has become their legacy.

"They have persisted where institutions have failed. In other words, it's through their endeavours that we are now in a position of knowing and understanding Hillsborough."

But it's worth examining what the cost of the families' persistence has been. There's been an enormous emotional toll. And there's also been a huge financial burden. For the first 20 years, the families had to pay their own way. And often they were up against public authorities with deep pockets.

"The state should do this job. The law should do this job. Investigators should do this job. It shouldn't have been left to families to raise money and shake collection boxes to fight a case, which is what the Hillsborough families did initially," Prof Scraton says.

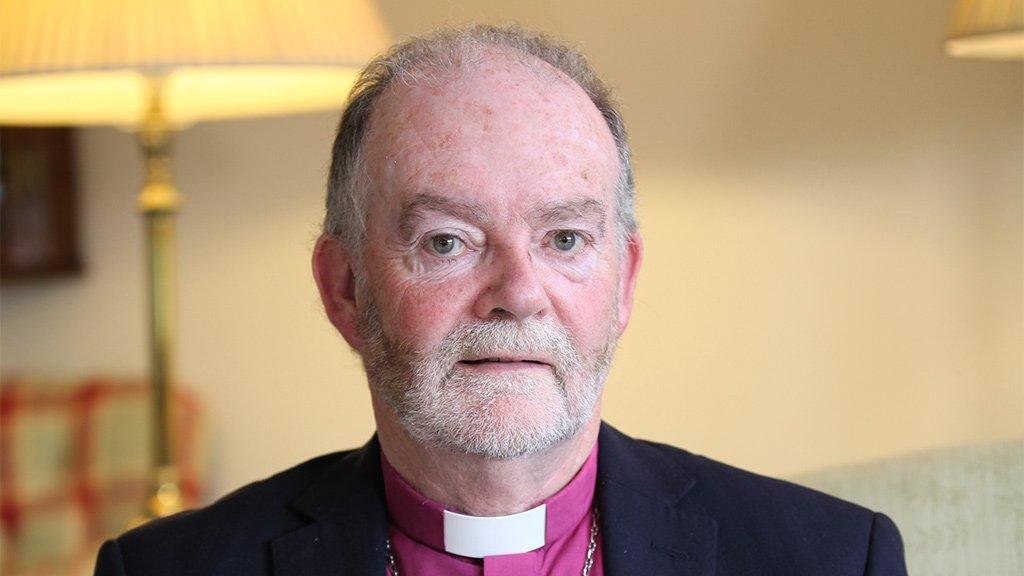

The former Bishop of Liverpool James Jones chaired the Hillsborough Independent Panel. In 2017 he wrote a report about the families' experiences with the subtitle: "To ensure the pain and suffering of the Hillsborough families is not repeated".

Bishop James Jones

He made 25 recommendations to government, for changes to be introduced to help victims of other public tragedies. The government has not yet responded to his suggestions.

One idea Bishop James is proposing is for there to be fair funding for families, so that they can participate equally in inquests involving public authorities. He also wants an end to those authorities spending limitless sums on lawyers.

He highlighted the fact that at the first inquests, 43 families clubbed together to pay for one barrister.

Others, like the Matthews family, were unable to fund lawyers at all.

"Some families paid for one member of counsel. We couldn't be included, so my brother was not represented," Debbie Matthews says.

"We really felt excluded, as when the families went into a private room with the barrister we weren't privy to the conversations, as we weren't a paying client. We had no input into the first inquests at all."

The police's lawyers were paid for by the public purse.

"I would argue that that is unjust," says Bishop James. "In fact, it's an affront to natural justice, that the state agency can be well-represented legally, and the families not at all. And we have to find some way of ensuring that an inquest is a level playing field for the families, as they come to find out about how and why their loved one died."

Bishop James is also a supporter of the idea of a "duty of candour" for public organisations like the police.

Hillsborough disaster timeline

15 April 1989 - Hillsborough disaster

1989 - 90 - Taylor Inquiry. First inquests. West Midlands Police criminal investigation.

1990 - Director of Public Prosecutions decides not to bring criminal charges

1997 - Stuart-Smith judicial scrutiny

2000 - Hillsborough families bring private prosecution against David Duckenfield and Bernard Murray. No convictions

2009 - Creation of the Hillsborough Independent Panel (HIP) after the 20th anniversary memorial service

2012 - (September) HIP report is published. Landmark moment which establishes that fans who died could have been saved. Leads to government apology by David Cameron

2012 - (December) First set of inquests quashed at the High Court

2013 - Two fresh criminal investigations launched. Operation Resolve - to investigate the disaster itself. And the IPCC (later the IOPC) to investigate the aftermath and alleged coverup.

2014 - 2016 - Second inquests held in Warrington. The verdicts establish that the 96 were unlawfully killed as a result of David Duckenfield's actions, and that the fans were not to blame.

2019 - David Duckenfield put on trial twice for manslaughter. The first resulted in a hung jury. The second, in an acquittal. Sheffield Wednesday Club Secretary Graham Mackrell is convicted of a health and safety offence, and fined £6,500

2021 - Trial collapses of Donald Denton, Peter Metcalf and Alan Foster who were charged with perverting the course of justice in relation to the aftermath.

Before it collapsed, the most recent Hillsborough trial highlighted the fact that police forces are not under any legal obligation to provide full information to a public inquiry. The Crown Prosecution Service has said this may be a matter which should be subject to scrutiny.

There are now growing calls for new legislation to clamp down on it.

The proposed "Hillsborough law" would place a legal duty on authorities to always be fully transparent, and to give full assistance to court proceedings, inquiries and investigations.

Barrister Pete Weatherby QC is one of those behind the idea. Mr Weatherby represented some of the Hillsborough families at the inquests. He has also acted for families bereaved by the Grenfell Tower fire, and he is representing some families at the Manchester Arena Inquiry, as well as the Covid-19 Bereaved Families for Justice group.

Pete Weatherby QC

He draws a line between Hillsborough and the other inquiries. "I see public authorities trying to defend their position rather than to do what they should do, which is to act in the public interest, accept their failures and learn from them."

He says the other family groups have watched the Hillsborough situation closely. "There's a very human lesson for them, because Hillsborough took 32 years to get to this inglorious end point, and though those families achieved a huge amount there are still massive problems," he says.

"Some of the Hillsborough families have gone and spoken to the victims of other disasters, and my observation is that families in other desperate circumstances have actually got a lot out of that process, and they've been informed of the rocky road ahead. But they've also been informed that you can make progress and you can make real change for the future to try to prevent things like this happening again."

Families, friends and survivors of Hillsborough reflect on their search for answers

With their own legal journey at an end, Jenni Hicks, Deanna Matthews and many of the other families now intend to turn their energy to campaigning for the Hillsborough law.

"The Grenfell families, and the Manchester arena bombings, we can see those inquiries taking the same twists and turns that we did," Deanna says. "It's bigger than us. It's a country-wide establishment problem. Because if something doesn't change now, it will repeat itself. And I don't want anybody to have to go through what we've been through."

Other inquiries have already benefited from positive aspects of the Hillsborough legacy. At the first inquests which began in 1989, the victims were referred to by number, not name. It was a dehumanising feature of the experience, which scarred the families.

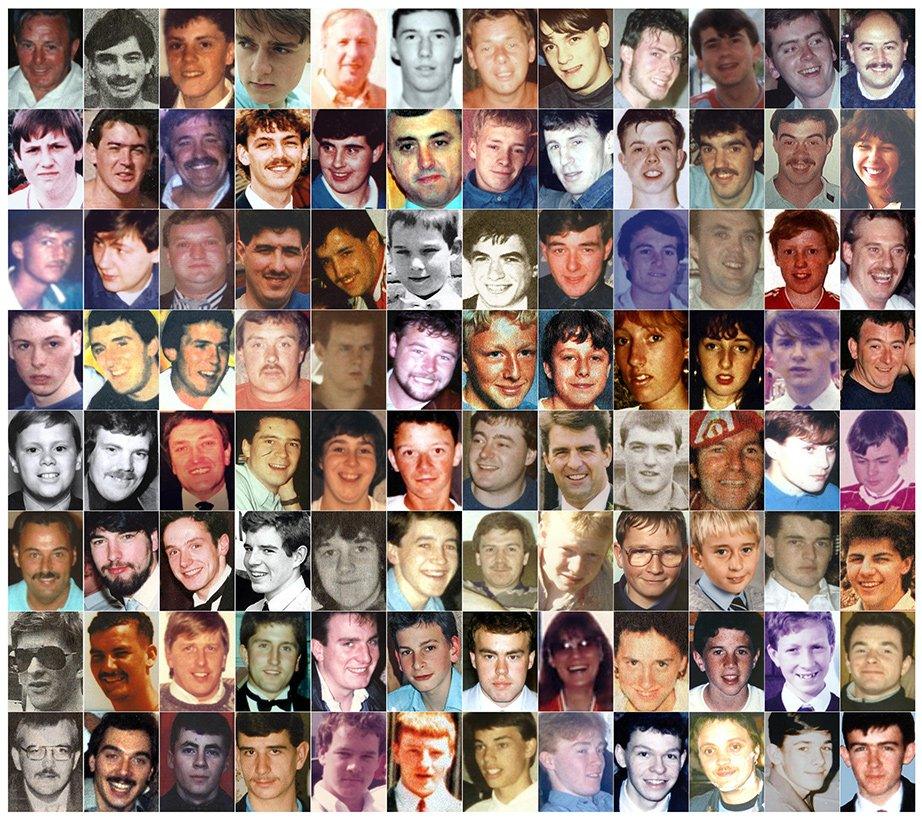

At the second inquests in 2014, there was a big effort to do things differently. For the first time in a British court, the hearings started with "pen portraits". Each family was invited to step into the witness box and pay public tribute to their loved one. Photographs and memories were shared. The 96 became known as individual people.

Copyright: Family handouts via Liverpool Football Club

Other inquiries including Grenfell and Manchester arena have followed the same format.

Pete Weatherby QC says the process is cathartic for the families but, "it's also hugely important in setting the tone for the inquiry, and the organisations involved. It makes real the claim that the families should be at the centre of things."

Sitting in a cafe opposite the court this week, the four Hillsborough women were starting to come to terms with the thought that their legal fight is over.

Deanna Matthews says she wants to dedicate her time now to ensuring that lessons are learned, and lasting change is made. "If our experience spares somebody else from having to go through that same level of devastation, then it hasn't been for nothing, and that's all we can hold onto now," she says.

Jenni Hicks agrees. "That's the only thing left that we can do now, for our 96. It's to make sure that nobody else gets treated the way that the Hillsborough families have been treated."