Economic Crime Act: What is it and will it find Putin's loot?

- Published

MPs have backed legislation to stop Vladimir Putin's allies from laundering money and hiding wealth in the UK.

The Economic Crime Act became law in March after being rushed through Parliament.

What is the UK's problem with Russian money?

The UK is thought to be awash with Russian cash and other money looted from the former Soviet Union.

That cash is buried in vast amounts of property - from office blocks to mega mansions - and the true owners are hidden in a web of secretive shell companies. These are organisations that only exist on paper and are registered in offshore tax havens.

The Economic Crime Act is meant to help end that - having been promised since 2016. It was shelved earlier in 202, amid much criticism - including from the fraud minister, Lord Agnew, who quit. Now, the invasion of Ukraine has prompted a government U-turn. Only part of the original plan has made it into law because there's not enough Parliamentary time to deal with all proposals.

The legislation:

creates a register of overseas ownership of UK land and property - with punishments for withholding details

overhauls Unexplained Wealth Orders

makes it easier to prosecute anyone involved in sanctions-busting

Why will the foreign ownership register matter?

If an individual owns a property, investigators and the public can find out who they are.

The police will often seize property belonging to British drug bosses because it's easy to identify, and will have been bought with their criminal wealth.

But discovering who owns property becomes more difficult if it is registered to an overseas company whose ultimate beneficiaries are hidden from view.

And that means it's harder to uncover money stolen from abroad as it's laundered through the British property market.

How does this hamper investigations?

Let's take the case of the first successful Unexplained Wealth Order (UWO). That's a legal tool that allows the National Crime Agency (NCA) to go to court to seize a property if there's no apparent legitimate source of the wealth behind the purchase.

Zamira Hajiyeva: Denied wrongdoing

UWOs are designed to take on incredibly rich people believed to have been associated with international corruption, organised criminals and their helpers.

The first target was Zamira Hajiyeva, the wife of an Azerbaijan banker. Her husband was jailed for embezzling millions from the state - Mrs Hajiyeva herself denies wrongdoing.

She was living in a £15m home near Harrods, where she spent millions over a decade.

The Land Registry showed the owner wasn't her, but a mystery company in the British Virgin Islands (BVI), a tax haven.

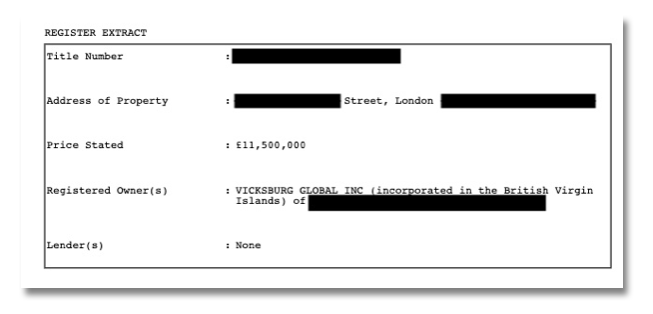

The Land Registry record showing who owned the home Zamira Hajiyeva lived in (some information redacted by the BBC for privacy law reasons)

It was only with the help of BVI investigators that the NCA could legally link Mrs Hajiyeva to the home and force her to explain in court how she could afford it.

So how will the new register work?

When a lawyer typically registers ownership of land and property, they will have to declare in public records who ultimately benefits from it. That means corrupt politicians hiding wealth in British mansions, office blocks and luxury apartments, may at long last, become visible.

The registry will apply to any property bought in the last 20 years, or since 2014 in Scotland.

If the person registering the property fails to identify the beneficiary, the property will be, in effect, frozen - the owner won't be able lease it, sell it or raise a mortgage.

Dirty money campaigners are delighted, but still have concerns. One fear is that it may be too difficult to prosecute lawyers or company agents who fail to reveal beneficiaries - because a court would have to be sure they had acted knowingly or recklessly.

Another concern is that the package has too many loopholes to ensure that ultimate beneficial owners become known. For instance, if someone uses a front company, registered in Panama, to legally own property on their behalf - and there's no shareholder who owns more than a quarter of that company, then the register won't reveal their identity.

"For the sufficiently determined owner of a UK property who wants to remain anonymous, we think the Act leaves loopholes," says George Crozier, spokesman for the Chartered Institute of Taxation.

Dr Susan Hawley of Spotlight on Corruption, an expert campaign group on dirty money, warns the law won't "unpack the Russian doll'.

Others predict that suspects - such as people who may be holding property for President Putin - could spirit wealth out of the country before the law is in force. The government abandoned its original proposal to give overseas entities 18 months to comply with the disclosure rules, by changing the deadline to six months. Labour had proposed 28 days - but that was defeated.

"I imagine that a lot of people in Kensington [one of London's most expensive areas] will be sticking property on Rightmove," says Helena Wood, a financial crime expert at the Rusi think tank.

"Practically speaking, these measures were never going to deal with [current] dodgy Russian assets. But they will mean it will be less likely that someone will want to hide money in the UK."

What about the Unexplained Wealth Order (UWO) proposals?

UWOs, created in 2017, are trumpeted by ministers as an incredibly powerful weapon - but they have in fact only been used against four targets.

High Court: NCA has to allocate huge legal resources to fighting money laundering cases

That's because the NCA lost one of its test cases in 2020, which not only exposed flaws in the power, but left the taxpayer with a near £1m legal bill.

When the Intelligence and Security Committee investigated Russia's role in the UK, external, Lynne Owens, the then head of the NCA, bluntly admitted that using UWOs to pursue the richest and most powerful targets carried huge financial risks.

And so critics of the government say the agency hasn't the financial clout or legal powers to make UWOs workable.

The Economic Crime Bill would permit investigators to target people who manage properties within complicated offshore arrangements, even if they're not the actual beneficiary. That will immediately widen the number of available targets. They'll also be given far more legal time to draw up a copper-bottomed case for court.

But most importantly, the NCA will be protected against crippling legal costs, providing they acted reasonable and properly.

Helena Wood at Rusi says the government could do more to financially protect the NCA across all its asset recovery powers - and failing to do so defeats the whole point of Parliament creating laws to investigate super-rich suspects.

Dr Susan Hawley says the government must seize the opportunity.

"The NCA needs one big properly-funded anti-corruption unit - from looking at professional "enablers", like accountants and lawyers, through to people involved in busting sanctions," she says.

"Without a significant boost in resources none of these measures are going to work."