Leicester: Why the violent unrest was surprising to many

- Published

After a largely peaceful protest, a few Muslim men try to break through police lines on Belgrave Road in Leicester, 18 September 2022

For decades, Leicester had a reputation as a model for cohesion - but the recent unprecedented unrest between groups of Hindu and Muslim men has raised difficult questions for a place that prided itself on its multiculturalism.

In the 1951 census, just 624 people with South Asian heritage were recorded as living in Leicester. Now, 70 years on, the city has one of the highest proportions of British South Asians.

The journey of the early post-war arrivals from the Indian subcontinent to the East Midlands can be traced back to two moments that took place a few years before that census.

Firstly, there was the 1947 partition of British India into two independent dominions - India and Pakistan - which saw the eruption of deadly religious violence, and left between 10-12 million people displaced. And then, there was the 1948 British Nationality Act - which gave every Commonwealth citizen the right to move to the UK.

Many people, whose lives had been disrupted by partition, heeded calls from their former colonial ruler to help rebuild the UK and start new lives.

Refugees crowd on top of trains during the partition of British India, 1947

From the 1950s, Indians and Pakistanis came to Leicester through so-called chain migration - via previous family members or villagers who were already settled in the city. Leicester was attractive - it was prosperous and had jobs available at employers like Dunlop, Imperial Typewriters, and the large hosiery mills.

Many of the new arrivals lived, at first, in affordable private housing around Spinney Hill Park and Belgrave Road - in north and east Leicester - the site of some of the most recent unrest.

Most came from Punjab - a region stretching across modern-day northern Pakistan and north-western India. They were Sikh, Muslim and Hindus - who had seen the effects of partition and religious hatred - and worked together in Leicester, often through the city's Indian Workers Association, to campaign on issues of race and to fight for equality.

By the early 1960s, wives and children from the Indian subcontinent had joined their husbands. And then - in the middle of the decade - East African South Asians, predominantly Gujaratis, began to arrive. They had faced increasing restrictions as places previously under British rule or protection - such as Tanganyika and Zanzibar, which became Tanzania, and Kenya - gained independence.

Many settled in Belgrave, Rushey Mead and the Melton Road areas of Leicester.

When Ugandan Prime Minister, Idi Amin, expelled Asians in 1972, Leicester City Council anticipated more arrivals. It took out adverts in the Ugandan press discouraging refugees, with a right to settle in the UK, from making the city their destination. But still people came, with many of the East African Asian community starting their own successful businesses - including in retail, hosiery and manufacturing.

Ugandan Asians arriving at Stansted Airport, 1972

Listen to Three Pounds in My Pocket - Kavita Puri hears stories of pioneering Asians who came to the UK from the 1950s onwards

By 1971, there were 20,190 people of South Asian heritage in Leicester. In response to the surge in numbers arriving from former colonies, the far-right National Front grew in popularity locally.

Emeritus Professor of Sikh and Punjab Studies at SOAS University of London, Gurharpal Singh, has lived nearly all his life in Leicester - after arriving from Punjab in 1964. His father was a manager at the Walkers Crisps factory in the city.

He recalls regular overt racism growing up, whether at school or from his neighbours, and the terror of seeing the National Front marching in the streets.

The far-right group's high point came in the 1976 local election, where they came within 61 votes of victory in Abbey Ward, and gained 18% of the total vote across the city. Throughout the decade, the anti-racist fight back saw British Muslims, Sikhs and Hindus working together. But on the streets, at times, there were clashes between anti-racists and the National Front.

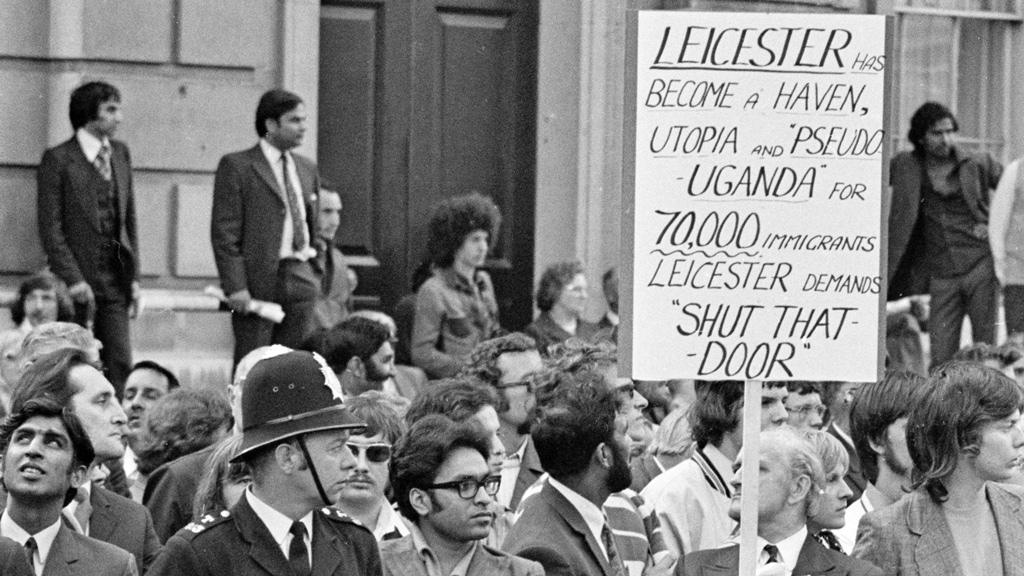

Anti-immigration protest in London, 1973

A change in the law in 1976 meant that local councils had become responsible for race relations - and by the 1980s, British South Asians were represented on the city council.

The local authority embraced the promotion of religious and cultural activities. During the decade, Leicester became a city of Asian festivals marking Diwali in the Belgrave area's "Golden Mile" with crowds of thousands - as well as Eid and Vaisakhi.

Leicester became "largely a model city", says Prof Tariq Modood, a founding director of the Centre for the Study of Ethnicity and Citizenship at the University of Bristol.

Celebrating the Diwali festival of light in Leicester, 2006

But there were times, when the politics of the Indian subcontinent spilt over into Leicester's streets.

Prof Singh recalls "random attacks" by Sikh militants in Leicester in 1984 after Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi's armed forces stormed the Sikh shrine, The Golden Temple, in Amritsar - leaving hundreds dead.

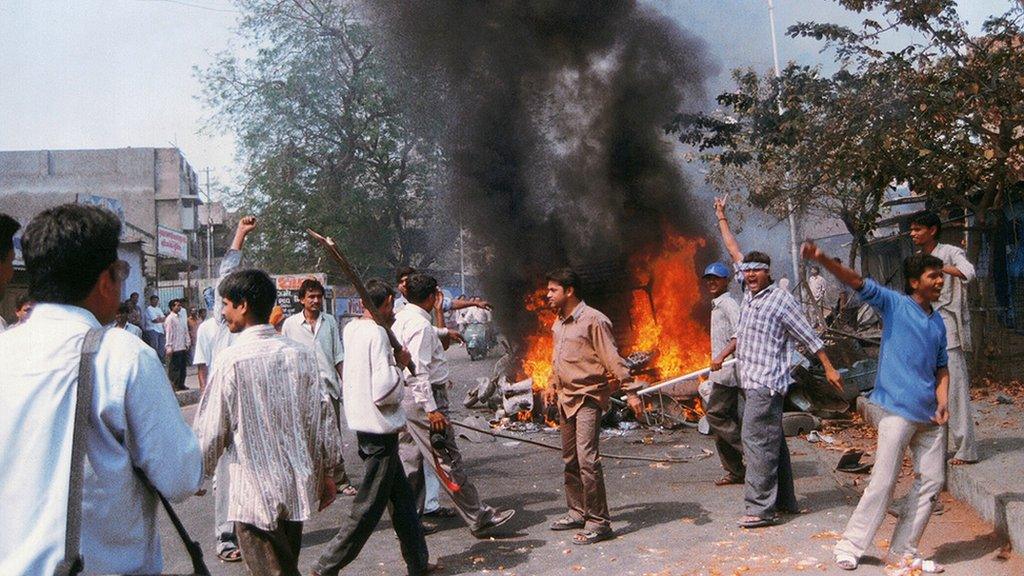

In 2002, Prof Singh watched on TV as events unfolded in Gujarat, in western India - after a fire on a train carrying Hindu pilgrims killed more than 50 people. Riots followed - and more than 1,000 people, mostly Muslims, were murdered in one of the worst cases of communal violence between Hindus and Muslims since Indian Independence in 1947.

"Those were the first riots [in India] covered in real time by the global media on 24 hour news," he tells me - recalling that in Leicester some took to the streets. "There certainly were widespread demonstrations in support of the victims, but no violence."

Rioting in Godhra, Gujarat, India, 2002

The politics of the Indian subcontinent has started to be felt in another way in Leicester since 2014, says Prof Singh, when the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) took power in India.

The rise of the BJP has fostered a brand of nationalism among the diaspora, he says. "The party is popular among Leicester's Gujarati Hindu community which manifests in the outlook and politics of the community."

Even more recently, Prof Singh says he has seen the demographics of the city changing again.

"South Asians have arrived from South Africa and Malawi, in particular, as well as India itself - where some have grown up with the hard-line politics of Hindu nationalism."

And then, he says, there are more local challenges for some in Leicester's South Asian communities - including the new arrivals. High deprivation and unemployment and social issues - with the city experiencing segregation of communities.

Leicester disorder:

Some tensions in Leicester had been brewing for a while, he says - and while it is still unclear what sparked the recent unrest, which has seen dozens of arrests, "what is surprising is the magnitude of violence. In Leicester it has never got to the point of confrontation before."

Videos shared by both Hindus and Muslims on social media, allegedly taken during the recent unrest, suggest anger on both sides.

Footage featured masked men pulling down religious decorations and banging on people's windows in Hindu-majority areas. One video appeared to show a man climbing onto the roof of a Hindu temple and pulling down a religious flag, another showed a flag being set alight.

While in predominantly Muslim-populated streets, footage appears to show the slogan "Pakistan Murdabad" - meaning down with, or death to, Pakistan - being chanted after the Pakistan-India cricket match at the end of August. "Jai Shri Ram" - meaning glory or victory to Hindu's Lord Rama - has been heard more recently.

"[Jai Shri Ram] has a devotional meaning," says Prof Modood, "but has been appropriated and is a charged term used by anti-Muslim Hindu extremists."

Fake information and misinformation - deliberately intended to mislead - are also being spread and exploited on social media.

Instigated by small factions in different South Asian communities here and globally, the posts use incidents in Leicester in an inflammatory way to further fuel tensions. The unrest reportedly being further stoked by influence from outside the city.

Leicester has seen many waves of migration, but this new violence between small sections of British South Asian communities is alarming. Such scenes between Hindus and Muslims is extremely rare in the UK - especially in Leicester. Many locals, including families who have now lived in the city for several generations, are shocked and disturbed by what they are witnessing on their streets.

"It is very disappointing," says Prof Modood, "that one of the cities where multiculturalism had taken root has had these scarring events."