The secret behind success of India's ruling party BJP

- Published

Many Indians seem to believe that Narendra Modi is a messiah who will solve all their problems

There is little doubt that the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which has ruled India uninterruptedly since 2014, has become the country's dominant party.

Led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, it has won two general elections decisively and despite losing states, steadfastly expanded its pan-Indian footprint.

The main opposition party, Congress, is adrift and enfeebled; the once-powerful regional parties appear to have exhausted much of their potential; and no credible challenger to Mr Modi is visible on the horizon.

Political scientist Suhas Palshikar calls the BJP India's "second dominant party system", external, the first being former PM Indira Gandhi's Congress which ruled the republic for more than half a century. The BJP is the only and first party to win clear majorities since Rajiv Gandhi of Congress did so in 1984 elections. After Indira Gandhi, who was murdered in 1984, Mr Modi is the "only leader to truly claim mass appeal almost throughout the country".

The BJP's electoral success is largely attributed to Mr Modi's charisma and the politics of religious polarisation and strident nationalism.

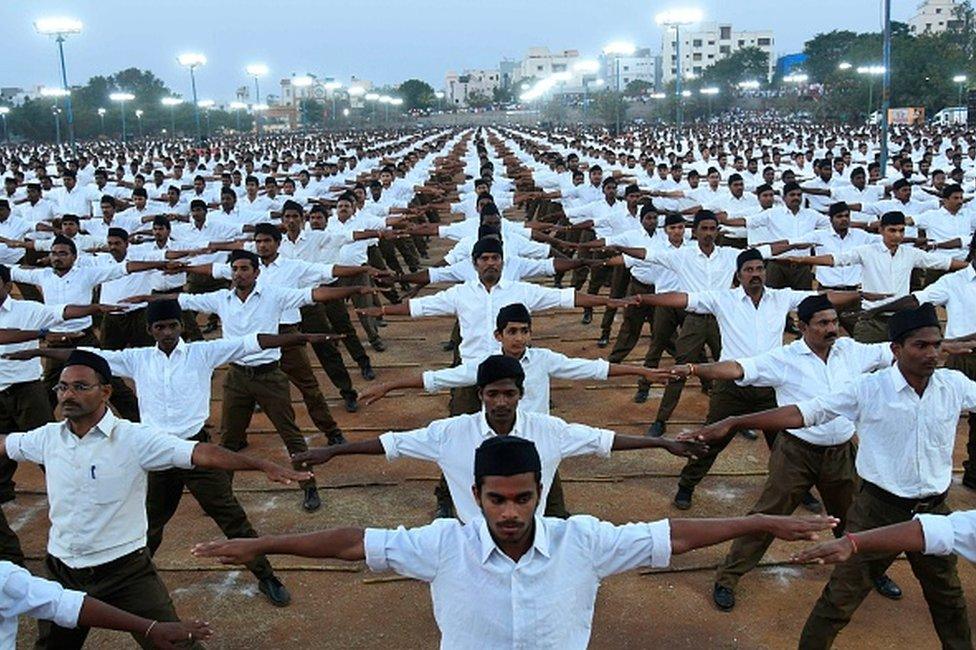

Its campaign is powered by an indefatigable network of workers, many of whom are foot soldiers of its ideological fountainhead, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), or Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), a group described by a political scientist as a "clamorous and militant sibling of the RSS".

In recent years, the BJP has also thrived on generous and "opaque funding, external"; and the unwavering support of a wide swathe of uncritical mainstream media.

But step back a bit and the "secret sauce" of success of the BJP, as well as the RSS, may well be their "unbending focus on unity", argues Vinay Sitapati, a political scientist, in his new book Jugalbandi: The BJP Before Modi. (The title loosely means a duet of two solo musicians in Indian classical music, and alludes to the partnership of two of BJP's well-known founders, Atal Behari Vajpayee and LK Advani.)

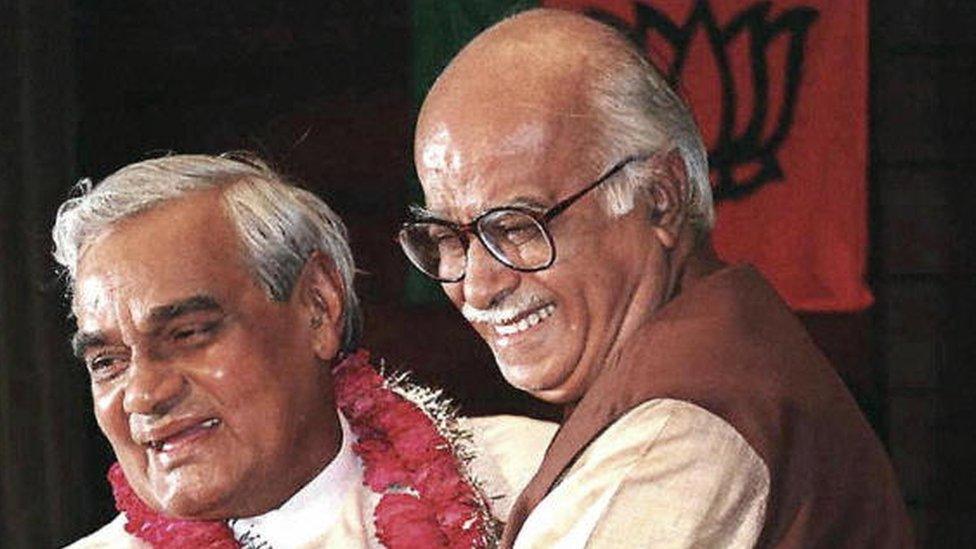

Atal Behari Vajpayee and LK Advani stuck together despite differences

From a very early age, cadres belonging to the RSS, the 95-year-old bedrock of Hindu nationalism, are taught a particular version of Hindu history where "glorious Hindus lose out because they stab each other in the back and they are not united", says Prof Sitapati, who teaches political science and legal studies at Ashoka University.

This is reinforced, among other things, through selective telling of history and the group's fabled physical training exercises which are "not just exercise, but exercise done together". Cadres are taught to march together, stand on top of each other in a pyramid, and play "games" that are more associated with team bonding exercises in private firms.

"All this is to highlight the importance of unity. This unifying belief has become an organisational ethic. This is not like every cadre based party," Prof Sitapati told me.

The BJP aims at uniting Hindus, who comprise more than 80% of Indians, and make them vote as one. That's why it downplays caste - which has traditionally divided Hindus and their political allegiances - "ups the volume on Islamophobia", and emphasises the importance of ancient Hindu texts, according to Prof Sitapati.

Like other parties, the BJP has suffered from its share of discord. It has been in power for barely 12 years of the four decade-long life in electoral politics. Being out of power meant there was no patronage to dole out to its workers for a long time.

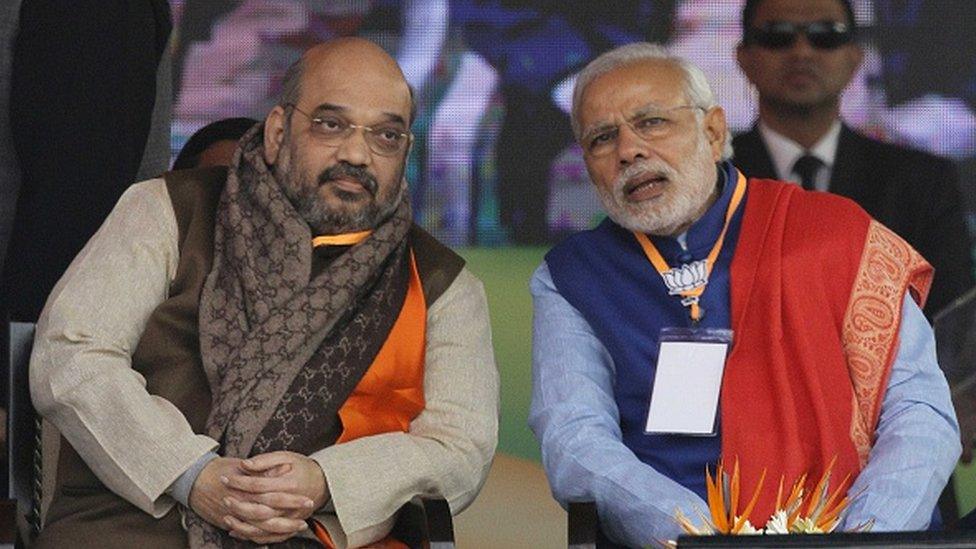

Narendra Modi and Amit Shah are the most powerful duo in BJP today

Relations between the top leaders - Atal Behari Vajpayee and Lal Krishna Advani - were often rocky. It is well documented, for example, how Vajpayee - now deceased - and a few members of his cabinet were unhappy with Mr Modi's continuation as the chief minister of Gujarat after the 2002 anti-Muslim riots in the state under the latter's watch. The riots began after 60 Hindu pilgrims died when a train carrying them was set on fire. Still the party stuck together.

"They have sometimes been like an unhappy family which stays together. Their obsession with unity is based on the deep understanding of the flaws of Indian society," says Prof Sitapati.

Political parties are coalitions of competing interests and factions usually held together by charismatic leaders, ideologies, organisational prowess and, in India's case, caste. Dissent and intra-party conflict are common. India's parties have been splintered by competing egos of leaders and factional feuds. Leaders have broken away from the Congress to form successful regional parties.

Nothing of that sort has happened with the BJP - yet.

Led first by Vajpayee and Mr Advani, and now by Mr Modi and Home Minister Amit Shah, the party, with ample support from the RSS, has held together . "I am revealing no secrets when I say that many BJP leaders dislike Mr Modi. Many BJP, RSS and VHP leaders I interviewed admired Mr Modi's fidelity to ideology and knack for winning elections. But many found him ruthless, self-aggrandising and solitary," says Prof Sitapati.

It helps that the BJP, in the words of Milan Vaishnav, a political scientist, is an "unusual party".

Most of the BJP's leaders trace their origins to the RSS

"It is the political wing of a broader constellation of Hindu nationalist organisations. It is very hard to separate the political entity from allied and nominally political entities associated with it. The networked model means that the BJP gains a lot of strength from its grassroots organisations and its dense networks help keep individuals inside the tent, so to speak," Prof Vaishnav, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington, told me.

It is not that dissenters have not left the BJP. "The puzzle is that they don't survive politically and return to the party. Perhaps the reason is BJP is a deeply ideological party and the ideological glue holds it together - and you will find this in the parties on the Left and Right," says Rahul Verma, a political scientist and co-author of Ideology and Identity, a book which explores the role of ideology in Indian politics.

BJP supporters celebrate as their party looks set to win a clear majority in parliament

Whether the BJP will stick together forever is impossible to predict. Its take-no-prisoners style of politics means they have thrown open their doors to defectors - often tainted - from other parties. This can lead to inevitable contradictions over ideological 'purity'. "How long you can manage the contradictions?" wonders Mr Verma.

For as long as the party is winning, surely.

That's why elections are the cornerstone of BJP's existence. Mr Verma says BJP's social base is expanding but their leadership still remains predominantly upper caste. That's another contradiction the party might have to grapple with in the future.

Critics believe BJP's unabashedly majoritarian politics is altering the "idea of India", one which was more tolerant and informed by secular values. "Their idea of India won," says Prof Sitapati, "because they worked as one."

Read more stories by Soutik Biswas

- Published25 April 2019

- Published24 May 2019

- Published23 May 2019