NHS crisis: The medics trying to fix the health service

- Published

Members of Oxford's hospital-at-home team - Prof Dan Lasserson, nurse specialist Yun Ody and Dr Jordan Bowen

The health service is in urgent need of help with doctors warning that unprecedented pressures could cost lives. Ambulances are queuing outside hospitals, emergency departments are packed and exhausted healthcare staff have more strikes planned. So do we need to do things differently to fix the NHS?

The government says the NHS has record numbers of staff and that it is tackling the pressures - including providing additional funding. But currently, many other records are being broken in England's health and care system for the wrong reasons. The latest NHS Digital figures show:

More than a third of all patients are waiting more than the target four hours to be seen in accident and emergency departments (A&E)

One in five ambulance patients are waiting more than an hour with crews before being admitted to A&E

There were about 133,400 full-time staff vacancies in NHS trusts between July and September last year

In the first week of January, on average each day, 14,000 hospital patients who were ready to go home were unable to leave - partly because of shortage of social care to support them

Even at a time of crisis, there are doctors and nurses rethinking healthcare.

BBC Panorama has been to Hull and Oxford where they are identifying problems early, and taking hospital treatment directly into people's homes.

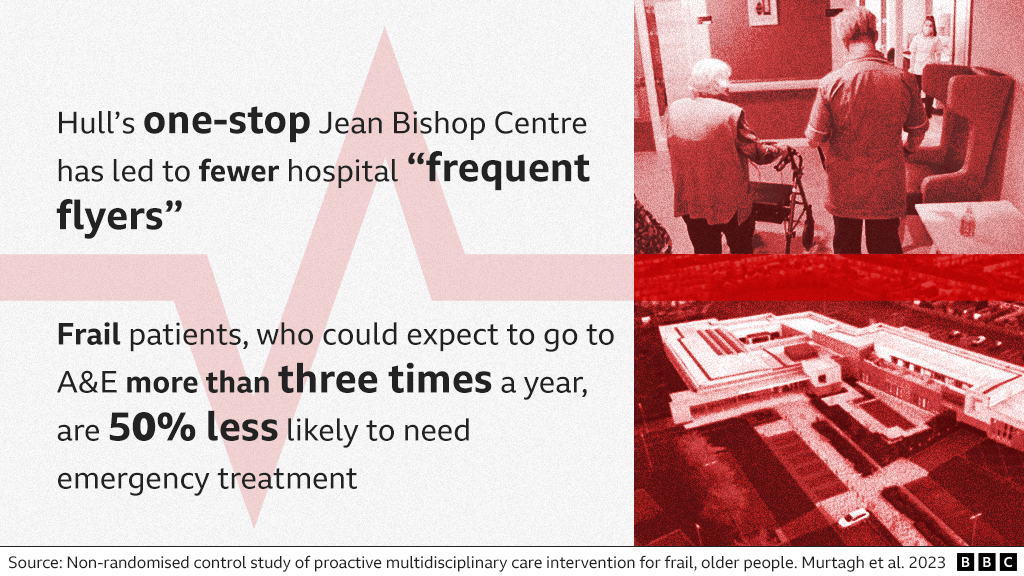

Picking up problems early in Hull

"We've essentially done 20 consultations in one here," says Dr Anna Folwell, as she finishes a medical consultation with 83-year-old Mary.

Rather than the rushed 10 minutes that's more usual in the NHS, Dr Folwell has spent more than an hour with Mary - who is having a full-body and life MOT at the Jean Bishop Integrated Care Centre in Hull.

Mary, accompanied by her daughter Jackie, was referred to the Jean Bishop Integrated Care Centre by her GP after recent falls

During her day-long visit, Mary also sees a nurse, pharmacist, physiotherapist, occupational therapist and social worker.

The NHS-funded centre is a one-of-a-kind hub that tries to anticipate and prevent problems among people who are frail - most of them are elderly.

In the UK, there are nearly 3 million people who can be described as frail - that's about 4% of the population - and research suggests they require about 40%, external of all hospital beds and GP resources.

Doctors, paramedics, and any health or care service in the area can refer someone here. Mary was sent by her GP after her third fall in the past year.

"I've never seen her look so frail. She'd been laid on the floor for a while," says Mary's daughter, Jackie, who has accompanied her.

"Frail? I looked frightful. Blooming 'eck!" adds Mary.

Consultant geriatricians Dr Anna Folwell and Dr Dan Harman set up the Jean Bishop centre for the NHS

Usually, doctors only have a partial view of someone's medical history, but Dr Folwell has access to all Mary's GP, hospital and social care records.

She concludes that Mary's blood pressure pills may be increasing her risk of falling. She adjusts the dose and removes another medication altogether.

The centre says these reviews consistently save more than £100 per patient per year - removing medications where the risks of continuing them outweigh the benefits for the patient.

It believes if that was replicated for all frail people across the UK, it could save about £270m annually - money which could be reinvested in services.

The centre's social worker sees Mary to assess if she needs more help at home. She also provides information about clubs and day centres, as loneliness can increase the risk of dementia and poor health.

Dr Folwell and Dr Dan Harman set up the Jean Bishop centre. Both are consultant community geriatricians - they specialise in the care of older people.

Twelve thousand patients have come through the centre's doors in the four years since it opened. They have needed fewer GP and hospital visits, but the biggest impact has been among some of the frailest patients.

"For those patients deemed to be frequent flyers - three or more emergency department attendances in the last six months - we reduce those attendances by over 50%," says Dr Harman.

"That's not by chance."

Panorama - The NHS Crisis: Can It Be Fixed?

The NHS is in a critical condition. The BBC's social affairs editor, Alison Holt, assesses the innovation and new ways of working that might offer the NHS the lifeline it needs.

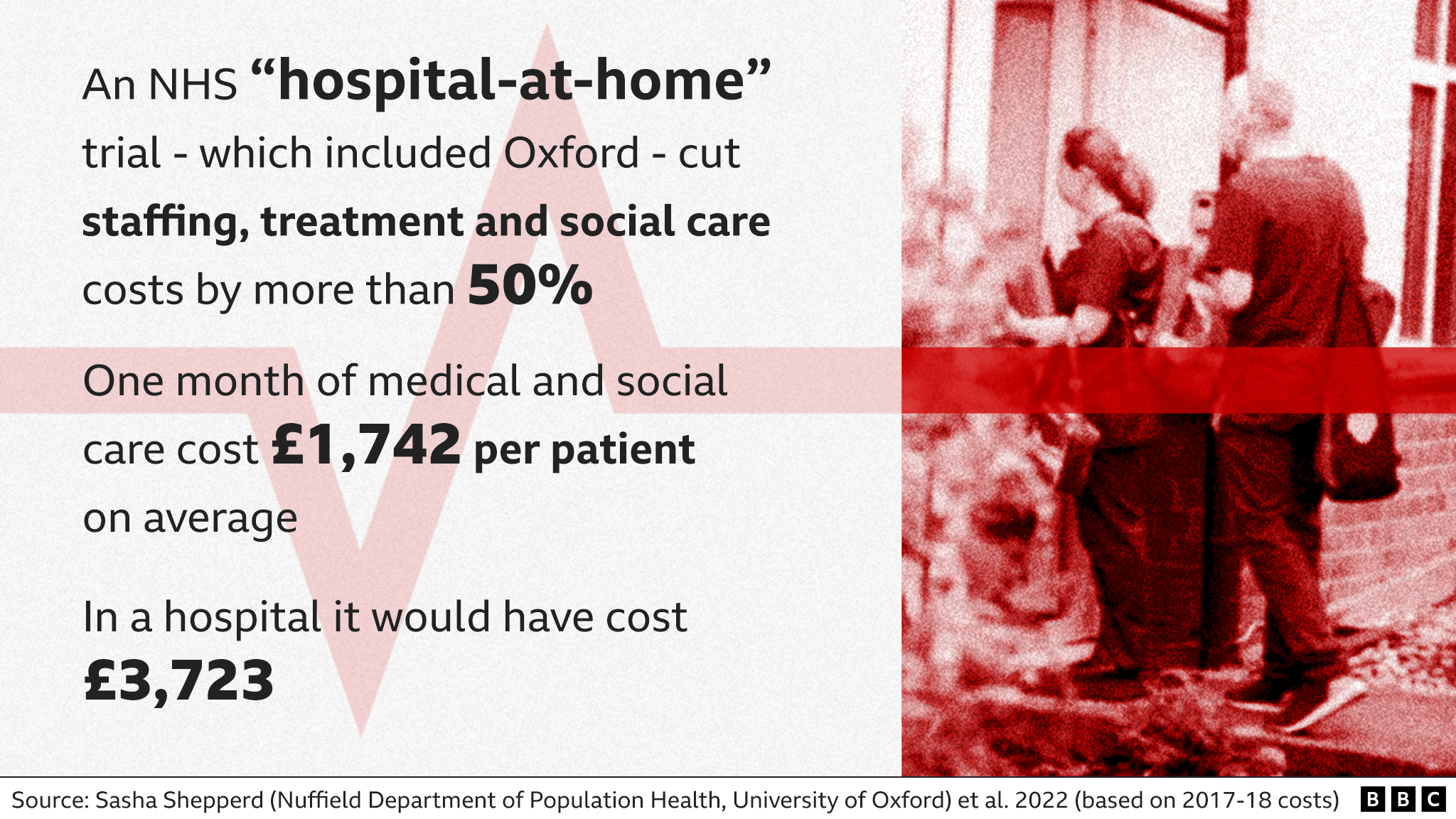

Oxford's 'hospital at home'

"The biggest thing is trying to explain to someone who is feeling unwell, why it is OK for them to be at home feeling unwell," says Dr Jordan Bowen.

"It's a massive change in thinking."

Dr Bowen says many patients, particularly those who are older, will get better quicker in an environment they know.

Dr Jordan Bowen tries to get people who arrive as emergencies home the same day

He runs a unit at the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford that tries to get people, who arrive as emergencies, home the same day safely.

They see about 70 people a day - 95% will go home.

Many hospitals have similar units - but here, they are going a step further.

They want to reduce the number of people who need to go to hospital in the first place, by providing high-level treatment at home.

"The hospital is full at the moment, 110% full," Dr Bowen says, studying a screen that shows the patients waiting in A&E.

He turns to Prof Dan Lasserson, who is standing beside him. "Could we get you and the hospital-at-home team to go out?" he asks.

Prof Lasserson was one of the first doctors in the country to start delivering this kind of hospital care in people's own homes.

Like Dr Bowen, he is a consultant specialising in the care of older people.

Paramedics, GPs and the John Radcliffe's own specialists alert the hospital-at-home team if there is a patient who needs medical care, but would benefit from being at home.

Prof Lasserson has also been asked by a heart specialist to visit the home of 91-year-old Ted - who fell last week. A bed has been moved into the family's front room, and Ted's wife and daughter are looking after him.

"I feel rotten," says Ted, who is finding breathing difficult - but doesn't want to go to hospital.

Prof Lasserson helps Ted have a drink before starting the medical treatment

New technology means Prof Lasserson can now treat much sicker people in their own homes.

He plugs a small ultrasound scanner into his mobile phone - and scans Ted's heart, lungs and kidneys. Black and white images on the screen show a build-up of fluid around his internal organs.

They also show his heart is not pumping properly. "This isn't squeezing very well at all, this left ventricle," says Prof Lasserson. "That's the problem."

Rapid blood tests are done and Ted's heart rhythm is also monitored. All while he is sitting in his armchair.

He is given intravenous drugs to help get rid of the excess fluid and a catheter is fitted.

Within a couple of hours, he has had treatment that would previously have taken visits to several different hospital departments and probably a stay on a ward.

The average hospital stay for frail, older patients, external is 10 days.

Researchers estimate providing a patient with hospital care at home costs about half that of providing the same treatment and care on a ward.

Nationally, the NHS is rolling out an initiative called "virtual wards". Technology is used to monitor patients, who need more routine care at home. They are visited if needed. The NHS says last month more than 10,000 patients were cared for in this way, easing pressure and reducing demand on hospitals.

Barriers to changing the NHS

In Ted's case, a nurse or paramedic will visit him each day at home - but, as he is not in hospital, the help he needs with day-to-day tasks falls to his family.

His daughter, Gill, returned from her home in France two months ago to help, but she has to go back in a week's time.

"My mum has mobility problems and balance issues, so often toileting and washing she can't do," says Gill. "She can't carry on doing what she's doing."

In the end, his family was only able to get a little social care help. They say it wasn't enough. Ted was eventually moved to hospital, then to a hospice, where he died a few weeks later.

If the Oxford "hospital-at-home" initiative is to be rolled out more widely, families will need more support in the community.

The government says there are 35,300 more doctors and 47,100 additional nurses working in the NHS now, compared to 2010.

But there remains significant shortages of GPs and district nurses, external. And the social care system, which supports people in their own homes and in care homes, is also buckling.

About 500,000 adults are waiting for council care services in England and there are a record 165,000 unfilled care jobs.

"We're no different in Oxfordshire. We are really struggling with the demand," says Stephen Chandler who runs the county council - which cover's Ted's area. He is also former president of Adass, the association which represents the people running local authority social care in England.

He says councils are doing everything they can to provide support, but to tackle staff shortages, care workers have to be valued and paid more. Most earn just above the minimum wage.

The Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC) says it is investing £7.5bn into adult social care over the next two years, including improving training and recruitment.

It also says this winter it is putting an extra £700m into getting people out of hospital more quickly, including buying more care home places.

Is change happening?

In both Oxford and Hull, change has been driven by determined doctors and there was energy and enthusiasm among staff.

Nurse specialist Yun Ody from the Oxford team used to work on a busy hospital ward. She prefers seeing patients in their homes, because she has time to get to know them. "You can listen to them and know what they need," she says..

In Oxford, nurse specialist Yun Ody prefers seeing patients in their homes

Patients we met were given valuable time that resulted in problems being picked up early, emergencies being avoided, or people being able to have their treatment at home surrounded by family. It gave them choices.

But at a time, when the NHS and the care system are facing such huge demand, many will question how realistic or possible it is to scale up projects like this.

The doctors in Hull and Oxford would argue we can't afford not to do things differently.

Tackling staff shortages will be key. And if that doesn't happen then the danger is the health and care system will continue to lurch from crisis to crisis.

Photography by Tom Pilston