Undercover police inquiry: Dad died without knowing the truth

- Published

Brian Higgins with his daughters, Monica and Noelle

The mammoth - but largely unreported - public inquiry into abuses by undercover police officers this week heard allegations of illegal activity dating back 50 years. But it is still nowhere near finished - and victims are starting to die without finding the truth.

In the final days of Brian Higgins' life, the 78-year-old was worried about the safety of the building site he thought he was on. Except it wasn't a site strewn with bricks and other hazards. It was a hospital ward.

"My dad campaigned for better health and safety and workers rights all of his life," says his daughter, Monica. "Even in his dying days, he was hallucinating that the curtain rails around the bed were loose scaffolding. He was telling people to stop work."

But years earlier, his career had been ruined. Every time Mr Higgins thought he had got a job, the firm would later withdraw the offer. And then the most extraordinary scandal revealed why.

His name, details and campaigning record as a trade unionist were found to be on what became known as the construction "blacklist" - a huge series of files used by major constructors to bar workers they thought were troublemakers.

"Dad just couldn't get work," says Monica. "When we talked about the blacklist, he said it was like being under house arrest. I don't know how he kept going. He always believed that there were undercover police involved. People thought he was paranoid."

Hundreds of participants

He wasn't. Not only was the blacklist a real thing, the Metropolitan Police admitted in 2018 that officers had passed intelligence on workers to the secret construction industry network, which oversaw the files.

That's why Mr Higgins was made one of the 248 core participants to the Undercover Policing Inquiry, launched to find the truth.

Today, the inquiry is nowhere near a final conclusion, and so Mr Higgins died never knowing why there was a 49-page file on his political and trade union campaigning.

Campaigners' banner outside the High Court

This week, the inquiry heard closing submissions on the first phase of its work.

Over the past three years, it has done much of its investigating in secret and only sporadically taken evidence in public - hearing from people claiming their rights were abused, but also from some of the surviving undercover officers.

There is are still enormous amount of work to be done - including looking at abuses in the 80s, 90s and 2000s, and what police chiefs and politicians knew about it.

But the inquiry has now taken so long it has outlived the government career of the minister who ordered it - former prime minister Theresa May.

She launched it in 2015, after mounting allegations of systematic abuses, including:

Officers tricking women into sexual relationships

Miscarriages of justice

Spying campaigns, including the one for murder victim Stephen Lawrence

Officers taking the names of dead children to create their fake identities

Since 2020, when it finally began hearing evidence, the inquiry has examined how and why Scotland Yard set up the "Special Demonstration Squad", in 1968, to infiltrate left-wing political protest groups.

And over the course of last week, the inquiry's chairman, retired judge Sir John Mitting, listened as lawyers argued over what to make of the first phase of the SDS's operations, up until 1982.

David Barr KC, the inquiry's lead barrister and the person who presents the evidence, summarised what increasingly felt like an astonishing list of wrongdoing.

He said the unit had essentially achieved nothing of merit in its first 14 years.

Anti-Apartheid campaign: Infiltrated by officers because it disrupted sports matches

Despite officers being sent undercover into protest movements, they had not stopped any unrest, uncovered any major crimes or plots to destabilise the nation.

"The level of intrusion into people's lives arising from SDS operations, particularly once long-term deployments became the norm, was very considerable," Mr Barr told the inquiry.

"Moreover, the intrusion resulting from the SDS's operations was into very sensitive areas of people's lives: their political lives, their financial affairs, their legal affairs, their families, their friendships, and even, in some instances, their sex lives."

Was any of this actually legal?

"No one appears to have considered whether the level of intrusion occasioned by SDS long-term undercover police deployments was justified," added Mr Barr. "There is a strong case for concluding that, had they done so, they should have decided to disband the SDS."

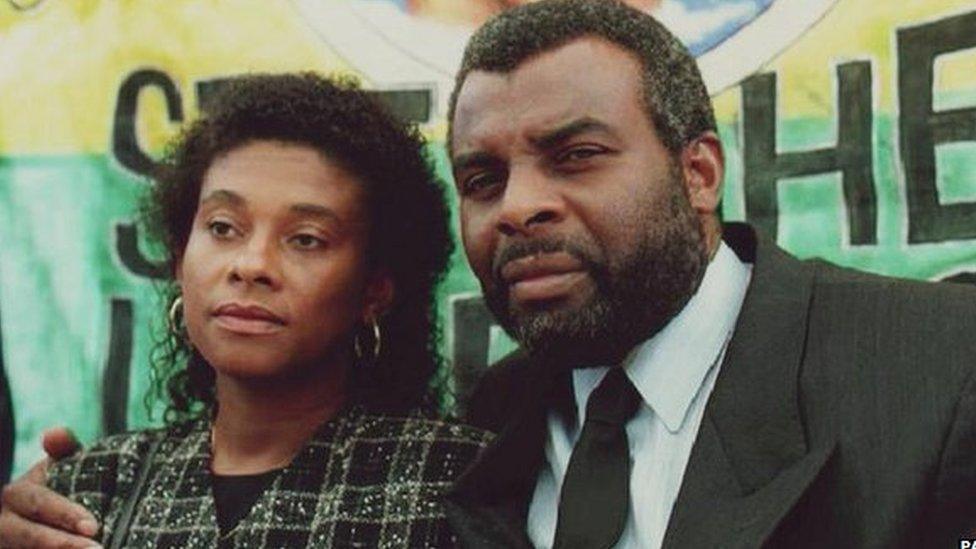

Stephen Lawrence murder: His parents' justice campaign was spied on in the 1990s, a whistle-blower has said

And that's why many of the core participants want the chairman to say now - rather than years from now - that all of what happened was completely unlawful.

Between 1968 and 1982, the period covered by the first tranche of the inquiry, there were at least five undercover officers who had relationships with women who were associated with groups they were monitoring.

Charlotte Kilroy KC, the barrister speaking for many of the women, told the inquiry there was not a single law that could justify what had been done. They had used women for sex - but also to gain access to other activists they were determined to target.

"These were women who were entitled to believe they were safe in their homes and private circles of friends and acquaintances," said Ms Kilroy.

"Instead of choosing officers who would respect the women they encountered and instead of taking all necessary precautions to counter the obvious risk of sexual relationships, both the MPS (Metropolitan Police Service) - and the men sent into their lives - had contempt for them."

All of this activity, she argued, was underpinned by a culture of misogyny that Scotland Yard knew about from both experience and a damning report commissioned in 1983. This "endemic" culture can still be seen today, she suggested.

"As the crimes of [former Met Police officers] David Carrick and Wayne Couzens have shown, these attitudes, and the tolerance for them in the Metropolitan Police Service, have horrific consequences for women," said Ms Kilroy.

Brian and Monica Higgins

Whatever the chairman does conclude about the first tranche of evidence, the entire inquiry won't conclude before 2026. It could still become the UK's longest public inquiry - and one of the most expensive. Last year, its total costs had topped £54m.

And while it continues, people who want answers about events when they were young men and women, will inevitably run out of time.

Brian Higgins died in 2019 - four years after the inquiry had been announced but before it had got anywhere near the evidence of blacklisting.

"He said to me that he did not think he would see justice in his lifetime," recalls Monica. "No amount of money would have brought back those years anyway."