St Patrick's Day: How England came to celebrate Irish culture

- Published

Birmingham is one of many English cities to hold a St Patrick's Day parade

The Irish around the world gather to celebrate their culture on St Patrick's Day, but in recent times increasing numbers of English people have been keen to join the party.

A man from Northumberland, the beginnings of the Northern Ireland peace process and gallon upon gallon of Guinness have all been credited with helping to make marking St Patrick's Day perfectly normal in the land of St George.

In fact, a survey conducted for the think tank British Future last year found English people were more likely to be able to identify the date of St Patrick's Day than St George's Day, external and suggested many were "too nervous" to celebrate their own patron saint on 23 April.

The first celebrations for St Patrick were recorded in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1737.

Mike Cronin, who co-authored The Wearing of the Green: A History of St Patrick's Day, external, said the earliest mention in England came in the 19th Century, when it was seen as important for the Irish Diaspora to attend Mass on 17 March.

"In later decades of the 19th Century, particularly in London and Birmingham, you would see very small, localised parades," he said.

"After the Second World War they became much more formal, usually based around different Irish societies such as the counties that people came from, so you might have the Dublin society or a Mayo society parade."

St Patrick's Day faded in England, Mr Cronin said, during the darkest days of the Troubles when there was a nervousness about celebrating Irishness.

"It didn't really exist. You would have had to be somewhere like Kilburn in London to have any sense that anything was happening at all," he said.

"Most of the city councils who were involved in parades started to view them as untenable, so the ones in Manchester and Birmingham stopped.

"The only one that kept on going through all the years of the Troubles was the London one and there was always a parade on the Sunday nearest to St Patrick's Day."

Events during the 1970s and 1980s retreated into "semi-private places" like dance halls, bars and churches until things started to change in the 1990s when a cooling in political tensions coincided with a period of popular culture when Irish eyes were definitely smiling.

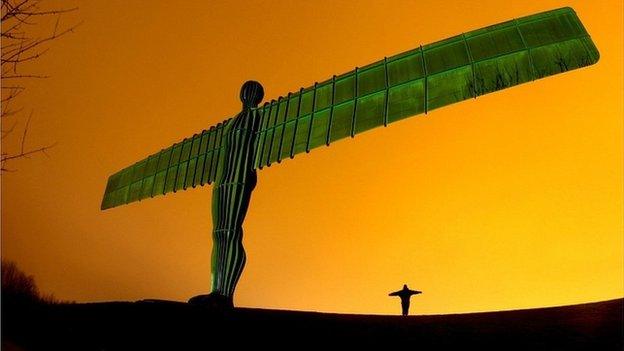

The Angel of the North is one of many English landmarks that have gone green for St Patrick's Day

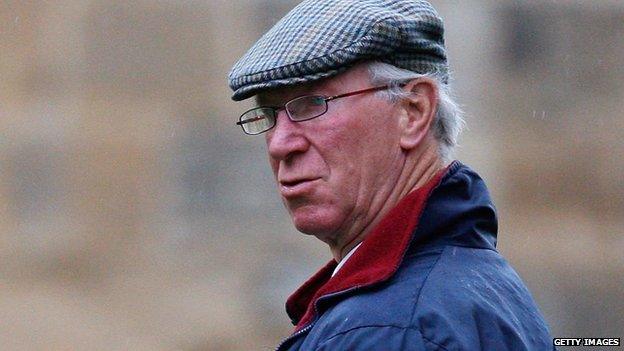

The Republic of Ireland won many admirers in the Italia '90 and USA '94 football World Cups, managed by Ashington-born Jack Charlton, who as a player had been a member of England's own 1966 World Cup winning team. England failed to qualify for the 1994 tournament - leaving fans in need of a team to follow.

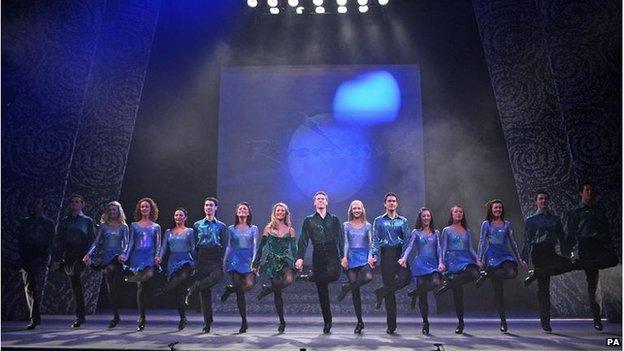

"There was Riverdance, the soccer team was doing well and suddenly Ireland was a cool and trendy place to be involved with," Mr Cronin said.

And then, there was the black stuff.

"There was a huge upsurge in the early nineties of the Irish-themed bar," Mr Cronin, academic director of the Centre for Irish Programmes at Boston College in Dublin, said.

"English people became much more used to the idea that they were going to this bar on this day because it was St Patrick's Day and Guinness would be giving out free hats and whatever else.

"By the late nineties Newcastle, Manchester, Birmingham and other places reignited formal public events and suddenly it was acceptable to be performing Irishness out on the streets again."

Englishman Jack Charlton led the Republic of Ireland in two football World Cups

Riverdance, seen here in 2007, helped Ireland appear "cool", historian Mike Cronin said

Thousands of Irish racing fans enjoyed an extended celebration at Cheltenham last week

Marketing expert Matthew Kearney, from Coleraine in Northern Ireland, said the commercialisation of St Patrick's Day had become "rife".

In a study conducted while he was working at Northumbria University, external, Mr Kearney said one respondent noted that shops were full of "all the cheap green tat you could think of" in the weeks leading up to 17 March.

"Guinness in particular have taken full advantage of this," he said. "St Patrick's Day is the quintessential celebration of Irishness, and Guinness has become the essential beverage on a day that is marked by the copious amounts of alcohol drank on it."

This year Guinness said it would hand out more than 325,000 hats in the UK and expect to sell 13 million pints worldwide.

But not everyone enjoys the drinking culture the event has become synonymous with. In his study, Mr Kearney, who now works for the Department of International Business at the University of Ulster, found many young Irish people felt "pressured" into drinking on St Patrick's Day.

The English, he said, were drawn to the celebrations due to their "jubilant party nature", in the same way people around the globe were.

Tellingly, two-thirds of people questioned in British Future's October poll felt St Patrick's Day was celebrated more widely in England than St George's Day.

Steve Ballanger from British Future said many respondents felt nothing was arranged on 23 April, whereas "St Patrick's Day has become an event".

"It has a big brewing company attached to it and they put a lot of effort into it but it's [also] become an event that people put in their diary and think about doing something [for]," Mr Ballanger said.

"Around St George's Day there's some inertia which doesn't happen with St Patrick's Day when you can walk along the street and see pubs advertising they're having a celebration.

Thousands of people helped turn London's Trafalgar Square green last year

"The fact that St Patrick's Day is celebrated so widely across Britain shows that there's space within British identity for it and that there's enough confidence within Britishness that Irishness isn't seen as a challenge."

In Ireland, Mike Cronin said, certain "Paddy's Day" traditions have died off.

"The notion of St Patrick's Day has changed," he said. "Only people of a certain age will attend Mass but every small town, village and city will have its parade. For most people it's a family day at the beginning of Spring."

Around the world, and especially in the US, tourist attractions and even rivers will turn green.

"The American strap-line," Mr Cronin said, "was 'the day that everyone's Irish'.

"That never happened in Britain because of the Troubles, but since the nineties, everybody knows about it and even if you're not Irish, St Patrick's Day is a day when if you're in the pub you will have a pint of Guinness."

- Published16 March 2014

- Published15 March 2014

- Published19 March 2013