The 'Heilsberg 39': Remembering England's WW1 prisoners of war

- Published

Frank Bower, 19, and James Grier, 22, died 10 days apart at the Heilsberg prison of war camp

Almost 100 years after a group of British soldiers died as World War One prisoners of war, 39 headstones have been erected at a cemetery in Poland in their memory. But who were the men who died so far from home?

Before World War One broke out the paths of Seymour Blewett, Frank Bower and James Grier were unlikely to have crossed.

Blewett was a printer and book binder in Truro, Cornwall, living miles away from railway clerk Bower in Ravensthorpe, West Yorkshire, and Grier in the Channel Island of Alderney.

But in 1918 they found themselves housed in overcrowded and insanitary wooden barracks, starving hungry and forced to work.

Each is believed to have died after spending time in the hospital at the Heilsberg prisoner of war camp in east Germany (now part of Poland) and were buried at the nearby Lidzbark Warminski cemetery.

Pte Bower was captured among other British and Portuguese soldiers during the Battle of the Lys

Between August and December 1918, 39 British prisoners of war would die at the camp where they had been held among thousands of Russian prisoners.

David Tattersfield, development trustee of the Western Front Association, has been researching the history of the "Heilsberg 39", external.

The Western Front Association, a charity which aims to educate the public in the history of World War One, has recovered and saved numerous documents, external including pension cards and service records that were due to be destroyed.

"There were three massive offensives in the spring of 1918," he said.

"The 21 March 1918, which is when Blewett was captured, the April offensive on the Lys, when Bower was captured, and the third one was the Chemin des Dames, when Grier was captured, any one of which could have potentially won the war for the Germans."

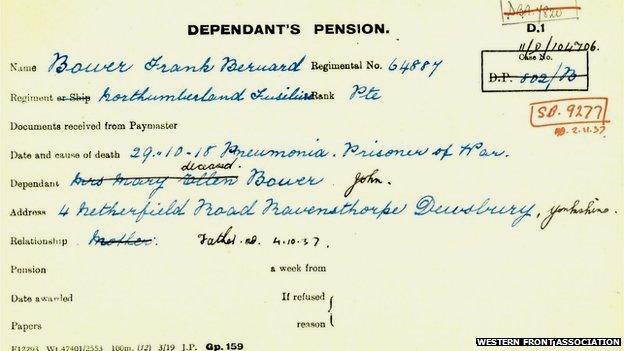

Pte Bower's pension card, saved by the Western Front Association, showed he died of pneumonia

Pte Bower joined the 22nd Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers, aged just 17 and underwent a prolonged period of training before being posted overseas when he turned 19.

He joined the Houplines sector, near Armentieres - supposedly a quiet part of the front. But this was about to change.

"He's sent out and lo and behold he doesn't ever fire a shot as he is in hospital with a stomach bug when the Germans launched a massive attack," Mr Tattersfield said.

Bower was moved to Heilsberg prisoner of war camp, about 80 miles east of the city of Danzig (now Gdansk), and it was here, on 29 October 1918, he died of pneumonia.

"There was a massive blockade of Germany at the time, so it was basically being starved on the home front," Mr Tattersfield said.

"The priority was to feed the army, then second came the civil population, who were on starvation rations, and bottom of the pile would have come prisoners of war.

"In the meantime they were being expected to work whether it was down mines or farms or in factories."

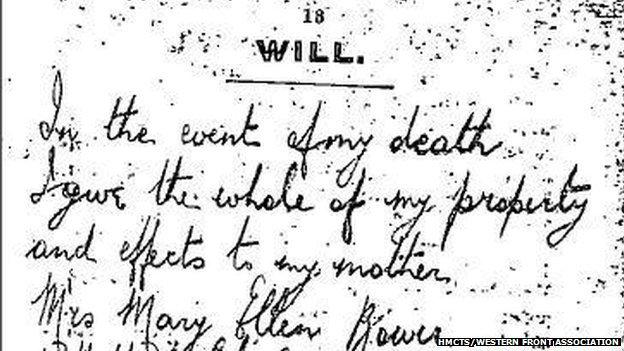

In his will Pte Bower left everything to his mother, Mary Ellen Bower

Also being held at Heilsberg was 22-year-old gunner Grier.

He was an early volunteer and is believed to have enlisted late in 1914 or early 1915, before being sent to France in May 1915.

It is not certain which unit Grier originally joined, but he ended up in 251st Brigade, Royal Field Artillery.

During the war Grier saw a lot of action and it was while his brigade had been sent to recuperate that he was captured in May 1918.

"There were beautiful landscapes of flowers blooming, beautiful May weather, it was quiet, nothing going on and then all of a sudden all hell breaks loose," Mr Tattersfield said.

"The Germans launched an absolutely massive attack through this area where people were supposed to be resting, in an area called Chemin des Dames."

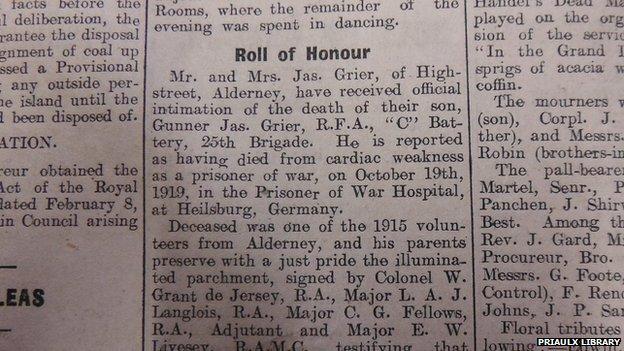

Grier and his comrades were "extremely unlucky" and almost all were captured. He was shipped off to the prisoner of war camp and died on 19 October 1918.

Gunner Grier's family have kept a number of old photos and his war diary

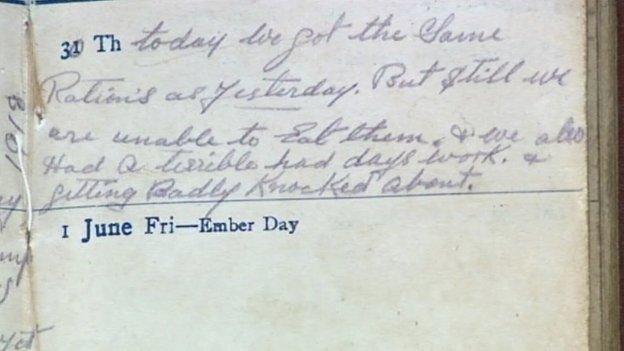

The last entry in Gunner Grier's diary said they were "badly knocked about"

A roll of honour entry in the Guernsey Evening Press for 22 February 1919 announced Gunner Grier's death

Following an appeal by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) and Mr Tattersfield's research, members of Grier's family were tracked down in Rainham, Kent.

Mia and Steve Mannion know very little about their great uncle James, but Mr Mannion has kept a number of old family photos and Grier's diary.

On 30 May 1918 it reads: "Today we got the same rations as yesterday, but still we are unable to eat them. We have also had a terrible hard day's work and are getting badly knocked about."

Mr Mannion said: "That's his last entry. He was captured and really badly looked after by his captors...he hadn't experienced any life at all. A sad loss I would say."

The Heilsberg camp contained mainly Russian and other eastern European prisoners, and it is believed that in October 1918, there were about 1,000 British PoWs at the camp, out of a total of 95,000 prisoners.

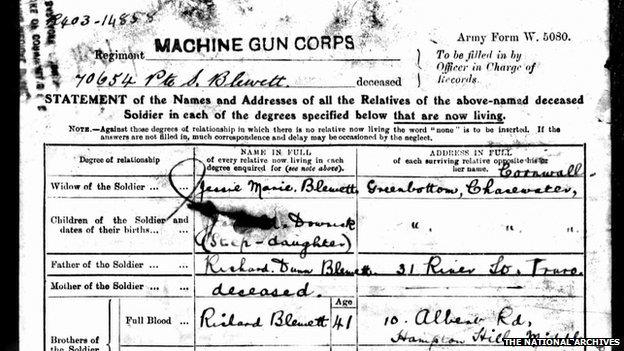

Pte Blewett's service record was saved by the Western Front Association

Blewett, who would become a husband and stepfather during the war, joined the Royal Berkshire Regiment on 10 December 1915 when he was 33-years-old.

He volunteered to be transferred to the newly created Machine Gun Corps and was captured on 21 March 1918 - the first of three spring offensives, called Operation Michael.

He would spend eight months as a prisoner of war.

While Germany signed an armistice with the Allies on 11 November 1918 - the official date of the end of World War One - Blewett was at the camp for another month before he died on 2 December.

"Blewett died after the war ended, which makes me think he would have been in hospital, otherwise he would have been making his way home once the war finished, suggesting he was incapable of getting home," Mr Tattersfield said.

The Germans made a cemetery at Lidzbark Warminski for the prisoners who died - containing 2,800 graves - with the British graves numbering 39.

The Lidzbark Warminski cemetery contains more than 2,800 war graves - 39 of which belong to British prisoners of war

The Imperial (now Commonwealth) War Graves Commission realised in the 1930s that the 39 British burials could not be located among the mass graves. However, the men were commemorated on the site.

This continued until the 1960s when it became apparent that the cemetery could no longer be maintained and the men were instead commemorated on a small memorial at the Malbork Commonwealth War Cemetery.

Now the CWGC has rebuilt the cemetery in Poland and erected 39 headstones for those that died at Heilsberg.

During his research for the Western Front Association into Blewett, Mr Tattersfield found that for the last 96 years Blewett's sacrifice been remembered on a memorial bearing the wrong spelling of his name - something the CWGC will now put right.

Peter Francis, from the CWGC, said: "The records were put together by the army (in 1919) and you sometimes find that a clerk mistyped a name or misheard a name and we think that is probably what happened in this instance.

"David has been able to help us with finding some of the original documents and it became clear that this was an error that we are able to rectify, to make sure we are able to honour that man correctly."

- Published16 May 2014