How schools inspired World War One recruitment

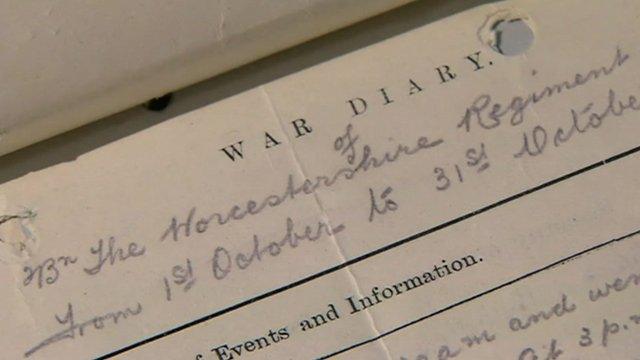

- Published

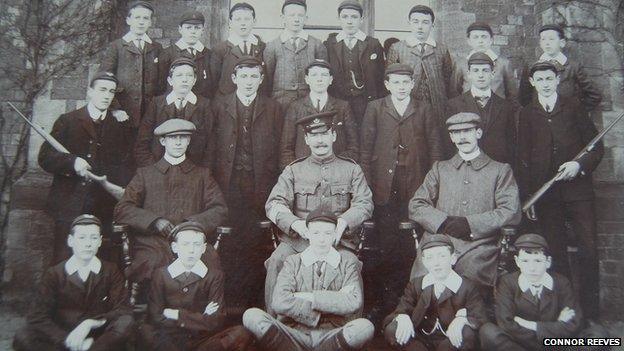

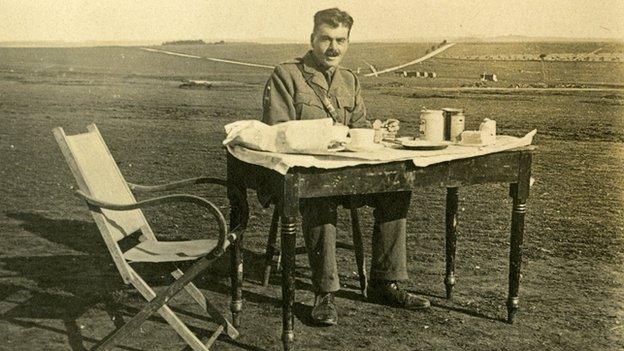

Sandbach school set up a new branch of its miniature rifle association during the war years

With the news war had broken out in August 1914, men of all ages and from all social backgrounds and occupations signed up to join the armed forces. But what role did schools play in that recruitment process?

Some men saw it as their duty to sign up, some were swayed by friends and family, others were swept up patriotism and propaganda.

In classrooms up and down the country, these themes and messages were getting through to teenagers, which prompted them to sign up for World War One as soon as their education was over.

"Children of all ages were encouraged to serve by their teachers," says historian Dr Barry Blades, who runs the Schooling and the Great War website.

"Head teachers seem to have acted almost as if they're recruiting sergeants; putting out pleas and making requests to their pupils and their alumni to do their bit - to make the school proud."

One of the ways they did this was by publishing a Roll of Honour, a list of ex-pupils who had joined up and which regiments they were in.

"If they were officers that was a mark of great institutional pride for the schools," said Mr Blades.

"The students who were at war at the time would always be in people's thoughts, their names would be read out at special assemblies and some that enlisted would write back to their teachers who would read the letters in class."

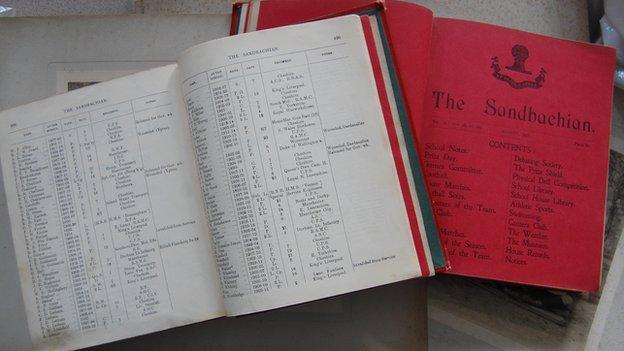

At Sandbach School in Cheshire, the roll of honour was published in its school magazine, the Sandbachian. It was published a couple of times when war first broke out, but then not published again until after the fighting had finished.

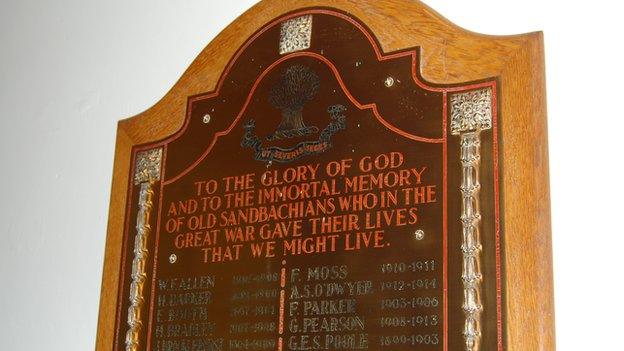

More than 200 students signed up for the war and a total of 35 students and one master were killed while on duty. Their names are now carved on a memorial in the school chapel.

"The headmaster actually spoke about how he was proud that lessons that had been instilled in the boys were taken into military life," said Conor Reeves, who is a sixth form history student at the school.

Sandbach was one of a number of schools that held "Empire days" and "Allied days" where students were encouraged to sing the national anthems of the allies.

A article in the Sandbachian showed that "Kaiser Wilhelm II had been the inspiration" for a new branch of its miniature rifle association being set up.

The Sandbach School Roll of Honour was published in the school magazine, the Sandbachian

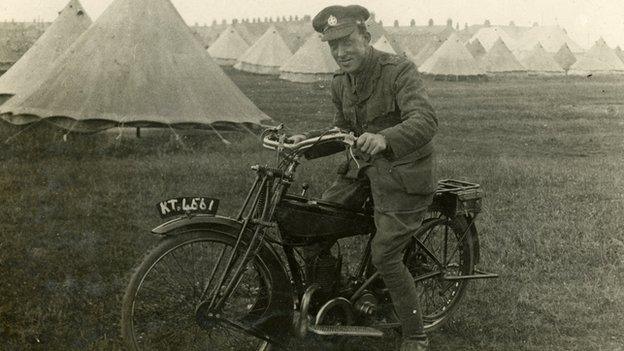

One of those who won many competitions at rifle shooting was 16-year-old William George Upton, who was also a keen pilot, said Conor.

"His school life pointed him in one direction, which was a career in the military," said Conor.

"He would take part in class debates about conscription, have geography lessons pinpointing where British troops were on a map of France and he even referred to his fellow pupils as 'comrades'."

W. G. Upton died on 4 October 1918, aged 20, after the Sopwith Camel he was piloting got involved in a firefight with the enemy over Roulers in Belgium.

"His plane was shot down and crashed five miles over enemy lines," says Conor.

The pilot is now buried at Dadizelle cemetery in Belgium.

Students were also inspired by their schoolmasters signing up with the armed forces.

At Shrewsbury School in Shropshire, 10 of its staff were sent to the front line, including best friends Evelyn Southwell and Malcolm White, who taught at the school between 1910 and 1915.

Their stories were told in a collection of their letters from the front published in 1919.

Malcolm White was killed in the Battle of the Somme on 1 July 1916

Evelyn Southwell was thought to have been killed by a sniper in October 1916

"They signed up after the death of their friend George Fletcher in 1914. In one letter which Southall writes to his father he says 'I must go now and take his place', " said school historian Mike Morrogh.

After both enlisting for the Rifle Brigade the men were deployed in different battalions.

They died two-and-half months apart in separate assaults on the Somme.

"White was killed on the 1st July 1916 going over the top, on the day that the British Army suffered its most rigorous casualty list," says Mr Morrogh.

"Southall was involved in an offensive in October when it was thought he was killed by a sniper in an open area. Both of their bodies were never found, so their names are on the Thiepval monument."

Mr Morrogh said their letters home gave a poignant picture of them as men and an insight into war.

The names of 36 Sandbach school old boys who died in WW1 are on a memorial in the school chapel

"You get a vivid sense of their affection for Shrewsbury and how they were popular figures with their peers and the schoolboys," he said.

"The boys wrote letters to them too and there was an enormous sense of pride at the fact they were serving."

While male teachers joined up to fight, they were replaced by retired teachers called "dug-outs".

"They were called this because they were dug out of retirement," said Dr Blades.

"In other cases they were taught by women and although this wasn't unusual in elementary schools, in secondary schools it was a major difference."

Dr Blades said it was not just teenage children that contributed to the war effort - younger ones would also often become "part of a home front".

"They would do campaigns like collect eggs for soldiers at local hospitals, make jam from locally-grown fruit to send to the front and young girls would knit and sew blankets," he said.

"Troops would really welcome these especially if they were old boys from the school from which they were sent."

The wartime contribution of Beeston Boys Brigade and how a nation marched to war.

What happened to Britain's teenage soldiers?

- Published17 July 2014

- Published14 June 2014

- Published20 May 2014

- Published24 March 2014

- Published14 January 2014