Spanish Civil War: The child refugees Britain didn't want

- Published

Young Spanish refugees arrived in Southampton aboard the Habana in 1937

When the Spanish Civil War broke out 80 years ago, many people fled their homes for safety, including nearly 4,000 children evacuated to England. Parallels have been drawn with the plight of unaccompanied young Syrian refugees - but how did the Spaniards cope with having to leave their war-torn homeland?

The children docked in Southampton in May 1937 - less than a year after fighting erupted between right-wing Nationalists and left-wing Republicans.

But their arrival followed much debate in the UK over whether to accept them.

Amid fractious relations across the continent, British prime minister Stanley Baldwin was keen to avoid involvement in the conflict and, along with his French counterpart Leon Blum, called for European powers to agree to a non-intervention policy, which was signed in September 1936.

However, signatories Germany and Italy "flagrantly flouted" it, says historian Adrian Bell, by sending military support to Nationalist leader General Francisco Franco, while the Soviet Union - also a party to the agreement - aided the Republicans.

"There's no doubt at all that the Germans regarded it as a kind of laboratory [for] testing the effects of bombing as a new way to fight wars," he adds.

General Franco (seen here in 1940) received support from Adolf Hitler during the civil war

Now in her 80s and living near Scarborough, Maria Luisa Patchett recalls how her seaside home in northern Spain was attacked by Nazi planes.

"My mother had just had twins... she had them in the house and she used to listen for the planes coming over. She used to say to us: 'Run… quick'.

"We used to hide and the planes [that] were coming over, they couldn't see us."

After they saw their house - where the babies were - catch fire following an air raid, "Mother ran and we all ran with her terrified. She managed to save one of the twins… who is still alive but the other one died in the fire."

Public demonstrations were held in British cities by trade unions and the Labour Party, which condemned Franco as "the assassin of Spanish democracy".

Spanish Civil War

Santander was one of many places that was bombarded during the conflict

On 17 July 1936, the Spanish military - supported by right-wing nationalists - stage a coup against the elected Republican government, which was backed by most of the left

Within a few days, they achieve control in some parts of Spain while Republican forces put down the uprising in other areas

General Francisco Franco emerges as the main Nationalist leader, while the civil war becomes a proxy war among European powers

Hundreds of thousands of people die before Franco's Nationalists win the war in spring 1939

By 1940, about 470 of the refugees who came on the Habana remained in the UK, with some fighting for British forces during World War Two

Sources: National Archives/Britannica/Basque Children's Committee

Calls were also made to accept refugees, which intensified after the infamous Nazi saturation bombing of Guernica in April 1937.

However, the evacuation of women and children from the besieged Basque Country was seen as a possible breach of the non-intervention policy by some in Whitehall.

The government's view was that, if people were removed, "then these are mouths, people, that don't have to be fed - in a way you are helping to prolong the defence of Bilbao against the attack by Franco," Mr Bell adds.

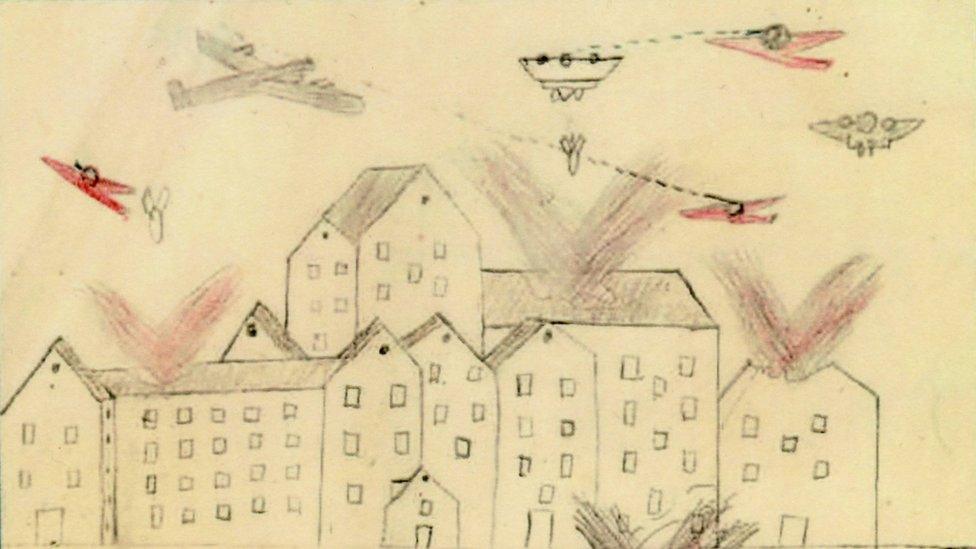

Pictures drawn by Spanish children showed bombing raids by warplanes

Some aid organisations also believed children would be better looked after closer to home in other parts of Spain or France.

In a letter, Baldwin remarked "the climate here would not suit" evacuees, possibly unaware that the Basque Country, like the UK, has fairly wet and cloudy weather.

Although officially impartial, the Conservative-led government - fearing the spread of Communism - has been criticised for being "more neutral to the Nationalists than it was to the Republicans", external.

Witness: Spanish civil war

It eventually yielded to campaigners, permitting British activists at the Basque Children's Committee (BCC) to evacuate nearly 4,000 children.

As the government said it would not take on financial responsibility for the refugees, the BCC spearheaded efforts to raise funds.

"You have to remember we are talking about the mid-1930s, a period of substantial unemployment, a lot of poverty in this country... it was the 'charity begins at home' argument," says Mr Bell.

"The trade unions put up quite a lot of money. It was done by tin-rattling, by public contributions."

Fruits and vegetables were collected at London's Old Spitalfields Market for child refugees

On 21 May 1937, about 3,860 children packed the ship Habana in Bilbao. They were accompanied by about 200 teachers, priests and other helpers.

Many of the children were told they would only be staying for three months.

Mrs Patchett, who was six years old at the time, joined her eldest brother and two of her sisters on the journey to Southampton.

"My mother and everyone where the Habana was docked was crying and sobbing, and we were terrified, we didn't know where we were going," she recalls.

"We were told on the boat that Franco's warships were nearby... the captain asked for help from the British warships who were nearby and they came and helped."

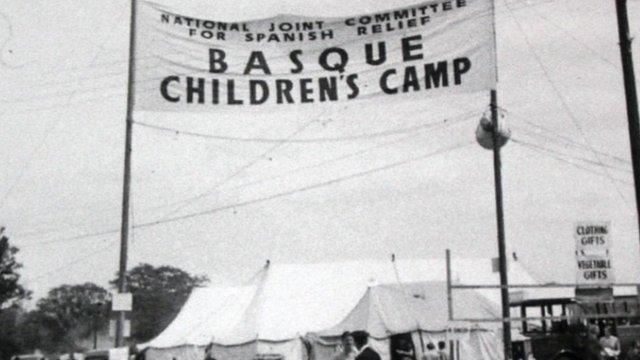

Pilots were told not to fly over the Eastleigh camp in case the children thought it was an air raid

After arriving in Southampton on 23 May, the children were sent to a campsite set up by volunteers in nearby Eastleigh.

Speaking in the BBC documentary The Guernica Children in 2005, Carmen Antolin recalled: "We got on the double-decker bus and as we were approaching the camps… we thought, 'All these tents, it must be [Native American] Indians' and we thought, 'Oh, we didn't know they had Indians'."

The refugees were split into three areas according to their parents' registered political affiliations: Republican, Communist and Nationalist.

While the children's health improved - thanks to food donations from locals - there were inevitable concerns about the psychological state of refugees separated from their families and homes. The problems were exacerbated because few British volunteers were able to speak Spanish while most evacuees didn't know English.

When the Basque Country surrendered to Franco's forces later in 1937, children at the camp broke down in tears, worried about their parents. Some even caused a "small riot", one evacuee recalled.

Refugee children receive their first meal at the Eastleigh camp

The majority of refugees did return to Spain by 1938, according to the Basque Children of '37 Association (BC'37A), although reports were received of some children ending up without their families and on the streets.

Those who remained in Britain were dispersed in groups to about 100 children's homes set up by the BCC, religious organisations and wealthy patrons around the country.

Mrs Patchett remembers how people in Hull organised for Spanish fisherman to greet her and other refugees arriving at the railway station.

"They had arranged for some Spanish fishing ships to come in and had asked the men to go the station… to make us welcome because they spoke Spanish and could make us feel at home."

Refugees staying in Bolton received donated dolls

There was mixed reaction to the refugees - many sympathetic locals gave food and gifts, while others were hostile to the newcomers.

At the same time, some Spanish boys got into trouble in and out of school, which triggered negative press coverage when teenagers broke windows following a confrontation with a driver in Brechfa, south Wales.

Along with a disturbance at a Yorkshire camp after complaints of food shortages, it led to questions in Parliament about when evacuees would return to Spain, and some of the refugees behind the trouble were sent back.

As the BC'37A notes, not all homes - known as colonias in Spanish (colonies in English) - were hugely successful, "nor did all the niños (children) behave like angels".

Former refugees met at an annual reunion in London in 2015

Without government aid, events were held where many refugees would perform Spanish songs and dances to raise funds.

Venancio Zornoza, who along with his two brothers, stayed in Keighley in Yorkshire, recalls the kindness of one family who "took us out to tea - and we kept in touch with them for about 80 years".

"The government didn't want us here... but really the British people they behaved so well to us, it was just unbelievable," Mr Zornoza says.

"I can never thank the British people enough and, whenever I get the chance, I do so because they were fantastic."

- Published24 May 2012

- Published15 September 2012

- Published28 June 2011

- Published4 May 2016