Battle of the Somme: How Britain learned the truth

- Published

Digital media means news of a soldier's death can now be shared almost instantly. But in an age of letters, telegrams and censorship, how did Britons learn the disastrous truth of the Battle of the Somme?

In the days following the start of the "big push" on the Western Front, the people of Tynemouth, near Newcastle, had collectively held their breath.

With dread, they watched the post-boy, who delivered the official death notices, appear in the streets around Milburn Place.

Onlookers felt a mixture of sympathy and relief as the boy walked to one of the first houses.

But then he crossed to another house. Then another. In the days that followed, he returned to criss-cross the area. Door after door, family after family.

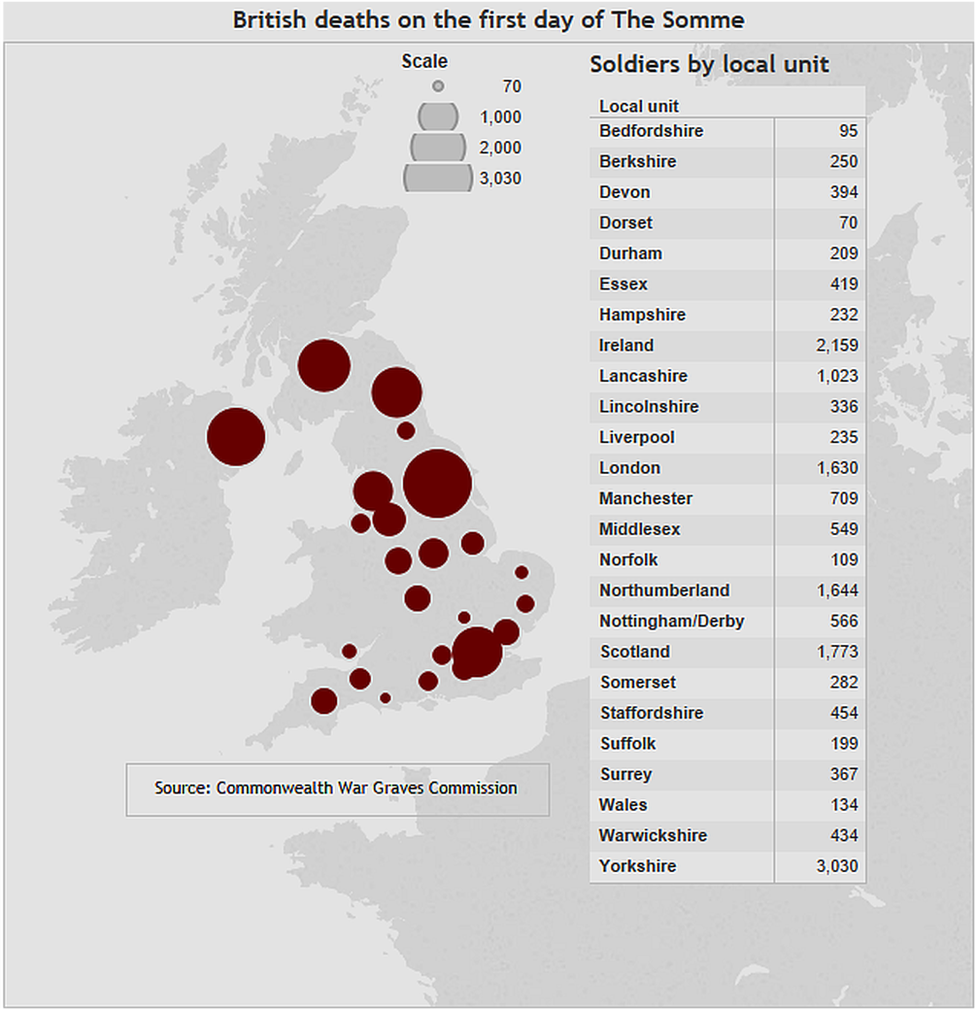

Eighty-five men from the town died on the first day of the battle alone. Across Britain, the scene was repeated as the legacy of the Somme took shape.

Some 20,000 British soldiers were killed in total on the first day. Yet, in a time of censorship, compliant media barons and slow communications, the scale of the disaster took weeks to become apparent.

"This is an age not just before the internet but before television and even public radio," Prof Mark Connelly, from the University of Kent, says.

"War news for the vast majority came via the written word - either through newspapers or letters - which the government did its best to censor."

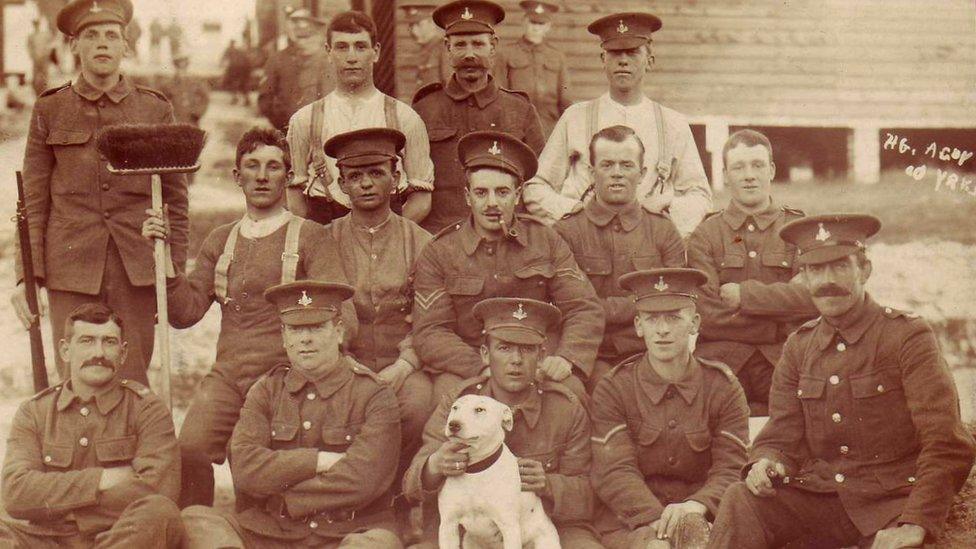

The battle was fought by a British army nearly 10 times the size it had been in 1914, packed with enthusiastic, if untried, volunteers.

Men from 10th battalion West Yorkshire in training. It would suffer the highest casualties on 1 July

Towns and professions had been allowed to join together, forming units such as the Artists' Brigade, Newcastle Commercial Battalion and the Accrington Pals. It was called the New Army.

Now whole communities would have an unprecedented emotional connection with single incidents in a vast war.

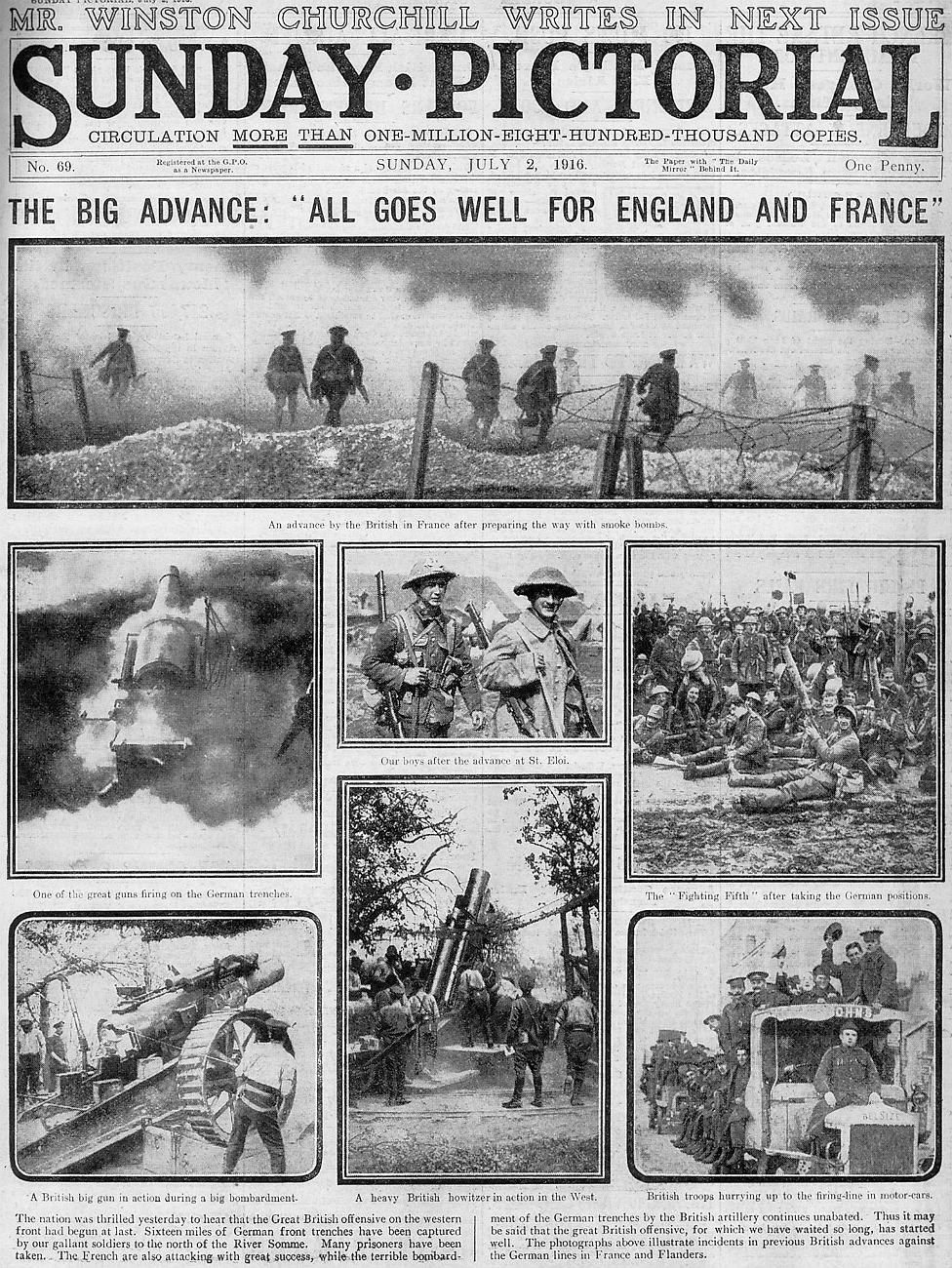

After soldiers had gone over the top on the morning of 1 July, an upbeat, official communiqué, timed at 11.30am, spoke of prisoners taken and trenches seized. It finished with the reassurance: "As far as can be ascertained our casualties have not been heavy."

This prompted jubilant headlines in many papers.

The anxious families may have allowed themselves a smile.

But at the same time, many papers carried a short paragraph noting German sources claiming the attack had been stopped with "heavy casualties".

"The generals were not sure what had happened that day, let alone the newspaper correspondents," says Prof Stephen Badsey, of the University of Wolverhampton.

"Even if they had known, if they had written 'Biggest disaster in the British army's history', it would never have made it into the newspaper. They would have been fired and quite possibly arrested under war powers."

"The official bulletin exhibits the heartless insolence of the war office in its most heartless form. With the guns in Flanders thundering in the ears of villagers here, whose relative are at the front, there is not a word about our troops."

Diary of the Rev Andrew Clark, of Great Leighs, Essex, 9 July 1916

Establishment links between press barons and the government, and a general patriotism among reporter and readers, meant critical analysis was hard to come by.

Official censorship of news was in theory voluntary - but breaches could lead to tough penalties. Officers did their best to monitor soldiers' letters.

"We tend to think of this censorship operation as if it was fiendishly clever and efficient," says Prof Connelly.

"It was neither. It was hit and miss. The good news comes first, but the bad news can't be stopped."

But in many cases, the news was not merely bad; it was appalling.

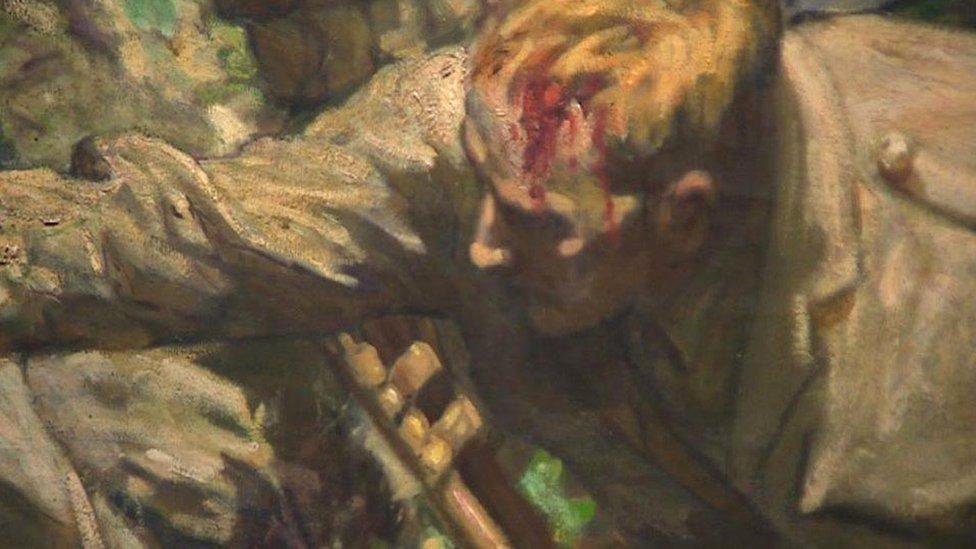

Medical orderlies look through missing soldiers' packs for personal items

Well-protected German machine guns and artillery had lashed troops struggling to cross No Man's Land. Many battalions - about 750 strong - had been blasted to pieces.

Of the 32 battalions which had suffered more than 500 casualties, 20 were New Army.

For the waiting families, the hours crawled by. Personal letters from soldiers dried up. Headlines remained positive but the language subtly changed; fighting had become "intense", resistance was "fierce".

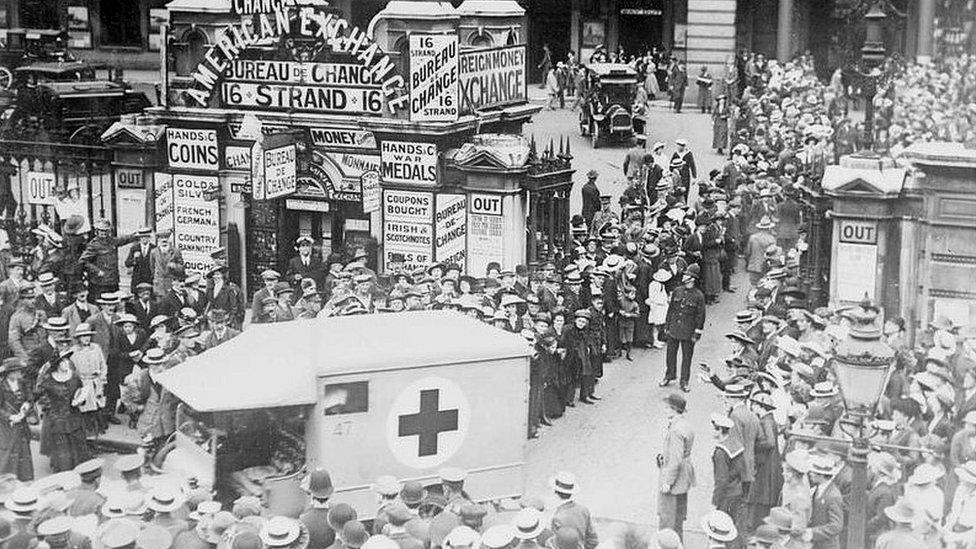

The first wider indication of what had really happened seems to have come from wounded troops being brought home. The first arrived just 48 hours after the start of the battle.

"There was only me there"

As a hospital train travelled through the Lancashire mill town of Accrington, a wounded soldier shouted out the window: "Accrington? Accrington Pals! They've been wiped out!"

As the rumour spread through the town, families converged on the mayor's house demanding news, but he was as ignorant as everyone else.

It would eventually be revealed the Accrington Pals had lost more than 580 men.

Despite the name the unit, officially 11th Battalion, East Lancashire Regiment, also drew men from Burnley, Blackburn, and Chorley.

"Posted notices of death or injury sometimes took a long time to arrive and it wasn't always the fastest way," says Chorley historian Steve Williams.

Somme wounded being driven out of Charing Cross station

"My father and brother were at the front and my mother fretted a great deal about them. She worried very much and her only way of knowing whether they were alive was reading the casualty lists. We children would gather around and listen and watch and look over her shoulder while she read and the tension was felt by all of us."

Mabel Lethbridge, munitions worker, London

"Mothers, working flat out at home, would send children, aged eight or nine, down to the Town Hall to read the casualty lists pinned up there and, obviously, bring the news back.

"It's hard to imagine but it must have been repeated over and over - there wasn't a town in the area that escaped."

As the wounded filled hospitals and halls across the country, hopes for an easy victory began to fade.

The machinery of the military mail had come back into action. Reassuring notes, sometimes just an Army-issue postcard, arrived at some lucky households.

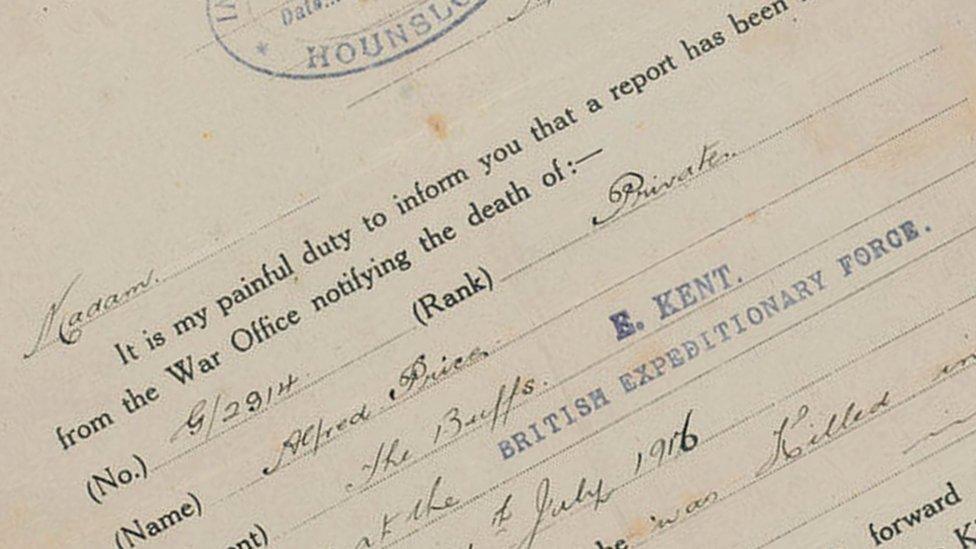

But all too often it was bad news. The families of officers who had died were officially notified with a telegram. The deaths of other ranks were reported on a pre-printed form, with gaps left for specifics.

Women from West Sleekburn, Northumberland, wait for letters to arrive in July 1916

"Sometimes whole streets are receiving the telegram boy knocking on their door, one after the other," says Prof Connelly.

"They are getting this terrible news, showing something very nasty has happened, while the headlines are still talking of success."

On Thursday, 6 July the Newcastle Journal was reporting "splendid results" and that, "according to very exact information, our losses have been very small".

The day after it carried a Press Association account of men being "mown down like grass". However, the reporter described the quoted soldier's testimony as "formless, lurid incoherence".

On the next page, headlined "Brave Tyneside Scots", was an eyewitness account of a local regiment successfully storming trenches under "hot" fire.

In fact, the Tyneside Scottish had been virtually annihilated. Of the approximately 3,000 men who went into the attack, nearly 2,250 became casualties.

On 10 July, the Journal told its readers: "Over the past week, the conduct of the war on every front has favoured the Allies". General Haig was reporting an "appreciable advance" seeing the "enemy retire in disorder". Two pages later were printed four broadsheet columns of casualties.

Similarly, in Bradford, the city's Daily Telegraph admitted it had been an "anxious week" but noted "very few deaths recorded".

The next day it printed an eyewitness account which admitted to heavy casualties but they were "chiefly wounded".

For soldiers and families, letters and cards were the main way of getting out news, good or bad

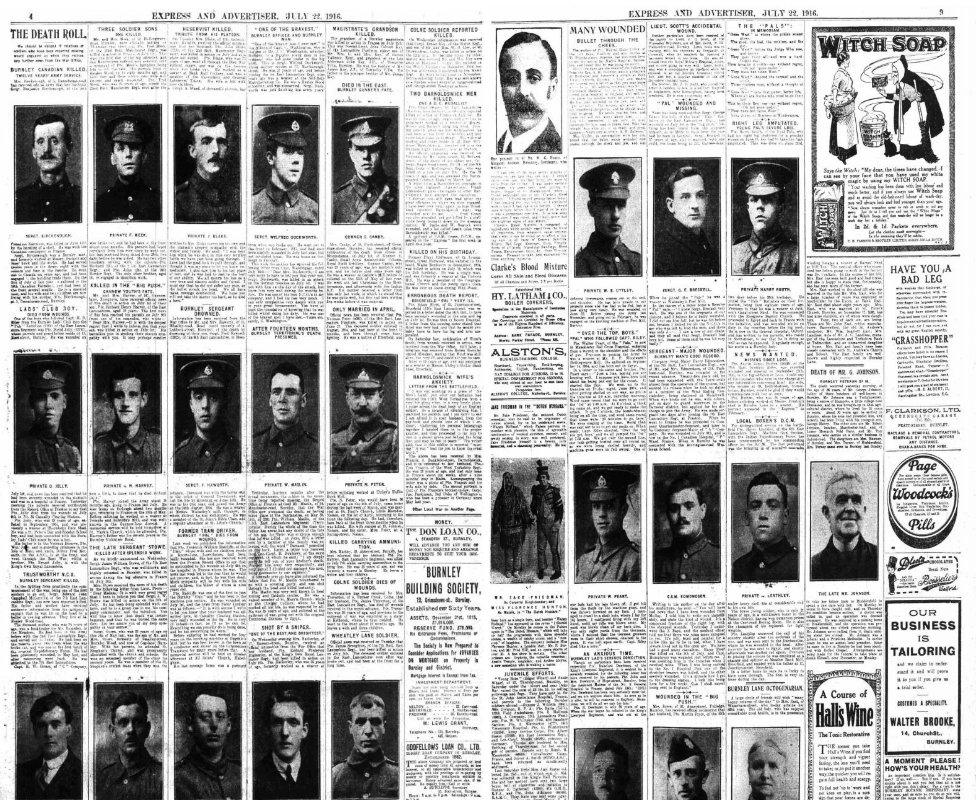

Two days later, a special edition came out. Under the headline "Bradford Heroes of the Great Advance" were published dozens of photographs of the dead and wounded. Second and third issues would be needed.

Of nearly 1,400 Bradford Pals who went "over the top", more than 1,000 were killed or injured.

As the scale of the disaster became increasingly clear, the newspapers attempted to walk a line between patriotic verve and credibility. Optimistic official accounts appeared side by side with the grim reality.

The select band of journalists allowed close to the front line struggled with patriotism, censorship and the enormity of what they were seeing. The reports were typically positive, but most later regretted their actions, insisting they were trying to spare the feelings of families at home.

William Beach Thomas, who was widely derided by the troops for writing in the Daily Mail of "glorious fights" and units "out win their spurs", later said: "I was thoroughly and deeply ashamed of what I had written for the good reason that it was untrue".

Ultimately, though, the true scale of the losses became clear.

The Times printed the official casualty lists - divided into officers and other ranks - first in hundreds, then in thousands. Day after day, throughout July and August and into autumn and then winter.

Most newspapers repeated assurances death had been "swift and painless". However some glimpses of the horror somehow seeped through.

Local papers were particularly keen to pay tribute to those who had fallen in the battle

The Cambridgeshire Independent Press on 28 July confirmed the death of Pte W Hankins who "lay on the battlefield three days and nights with his left leg and arm smashed".

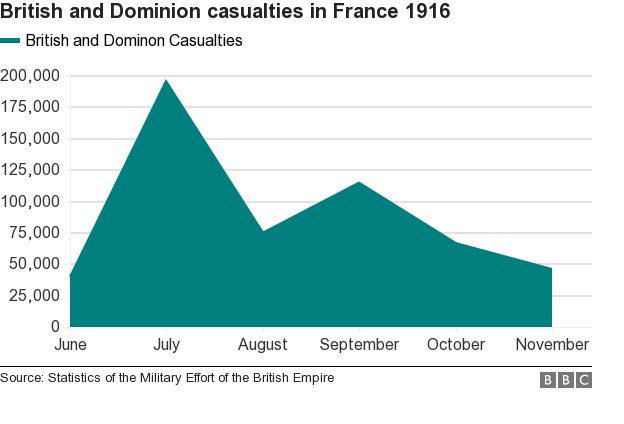

About 14% of the British casualties on the Somme fell on the first day. But new attacks, as well as the gradual sorting through the aftermath of 1 July, meant families could never rest easy.

The public were desperate for news. Newspaper supplements, along with magazines such as Illustrated War News and The Sketch, bulged with illustrations and descriptions of varying accuracy.

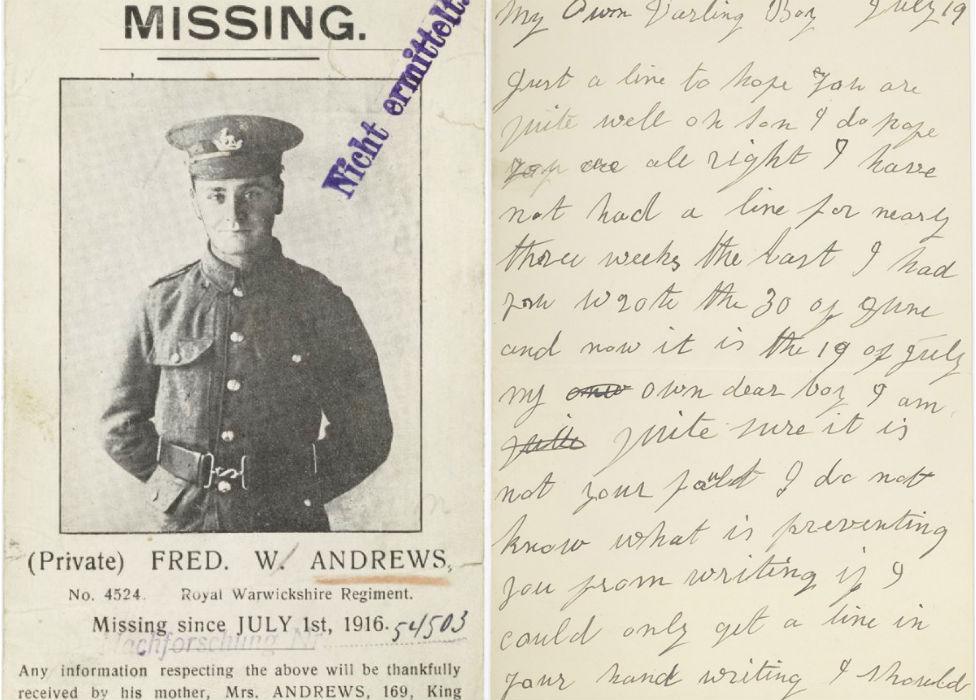

But often the endless pages failed to provide the most important information of all - the fate of the thousands of soldiers who had been posted as missing.

When the official channels could provide no more information relatives might seek out comrades to see if they could add details or give clues. Newspapers printed appeals from families who would be "grateful for information about...".

More often than not, these glimmers of hope were snuffed out, or faded as the weeks passed.

Pte Fred Andrews, of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, went into action on 1 July. His mother wrote repeatedly in the silence that followed. Her letters were returned, stamped: "Missing".

"Oh son I do hope you are all right I have not had a line for nearly three weeks the last I had you wrote the 30 of June and now it is the 19 of July my own dear boy I am quite sure it is not your fault I do not know what is preventing you from writing if I could only get a line in your hand writing I should feel better."

Letter from Elizabeth Andrews, Ladywood, Birmingham, to missing son Frank

In response she had cards printed with Fred's picture and details and sent them out to hospitals and even the Germans, in the hope he was a prisoner.

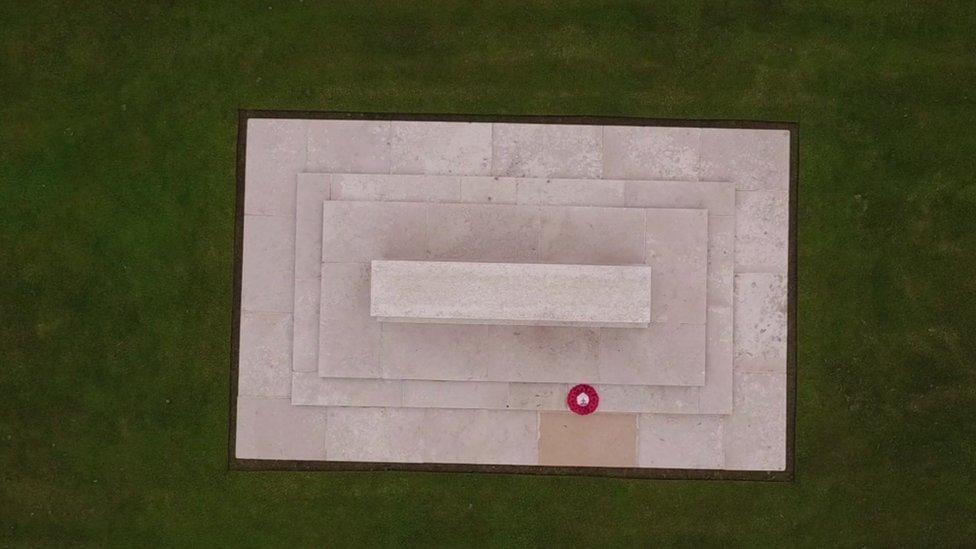

Pte Andrews' body was found some weeks later. But tens of thousands of families never even had that comfort, names in stone being their only memorial.

Possibly even more heart-wrenching was the fate of 25-year-old John Duesbery, from Swinefleet, Goole, East Yorkshire. He disappeared as fighting ground on into September and his mother endured empty months until he was declared dead in August 1917.

It is impossible to imagine the feelings when, weeks later, his pocket book was returned to them. Inside was a last letter, written as he lay dying.

"I am laid in a shell hole with 2 wounds in my hip and through my back. I cannot move or crawl. I have been here for 24 hours and never seen a living soul. I hope you will receive these few lines as I don't expect anyone will come to take me away."

Pte John Duesbery, journal, 16 September

Sometimes the system went wrong. Cousins Ralph and George Bilton, from Framwellgate Moor, in County Durham, went into the first day of the battle with the Durham Pals.

Days later, Ralph's mother received news he had been killed. Like many others, she refused to believe it and demanded more checks.

Incredibly, it turned out Ralph was indeed alive. But the confusion had only come about because he had used his jacket to cover George's body. The tragedy did not move far from home.

James and Edith Harper, from Newark, Nottinghamshire, found out their son, also called James, was dead when neighbours came to offer sympathies. A friend had been told in a personal letter that beat the official post.

In late August, as communities absorbed the scale of the loss, the government made the decision to release a documentary film about the battle.

Cinema was still a novelty and Battle of the Somme represented a milestone in both filmmaking and propaganda.

For a public whose previous images of war had been based on illustrations of strapping Tommies chasing cringing Huns, it was a revelation.

While some scenes were staged The Somme film showed genuine footage of the dead and wounded

Most of the footage was genuine with only a few battle sequences mocked up for the cameras. While shying away from the worst of the carnage, it showed plenty of mud and death.

Some commentators were shocked by its frankness but the public were spellbound, feeling a new understanding for the troops. It is estimated 20 million people, half of the population, saw it.

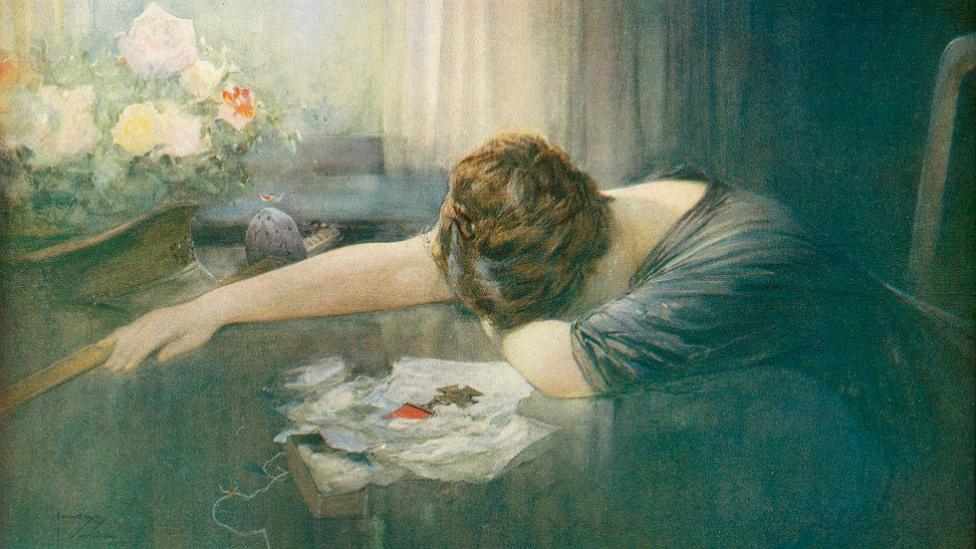

As the battle ground on, the emotional toll grew. Many windows had blinds drawn, families wore black.

With overt displays of grief deemed socially unacceptable, other outlets were needed.

"There is an explosion in unofficial street shrines, which existed before but really take off during the Somme," says Prof Connelly.

"The dead are buried abroad and contact with the living is intermittent, leaving many people with no focus for their fear or grief."

Street shrines sprang up in many streets, sometimes near churches but often on any prominent wall

Whatever the personal depths of shock and grief, society at large seems somehow to have absorbed the blow.

Support for the war was, on the surface at least, almost unaffected. A campaign to cancel the August bank holiday to aid war production received widespread backing.

"By September the dead have become a reason for fighting in themselves," says Prof Connelly. "How can a compromise peace be considered after this?

"You have gone through all of this to give Germany even a smidgeon of what they want? It would be letting the dead down."

"A virtue is made of the situation by the authorities," says Prof Badsey. "Men are sacrificed, never slaughtered. And it is always brave and heroic. Devastated units have covered themselves in honour."

The Somme campaign came to a muddy end in November and the nation was left to count the cost.

More huge battles in 1917 and 1918 - Passchendaele and the 100 Days - caused casualties that approached those of the 1916 battle, but nothing compared with the shock of the first days of the Somme.

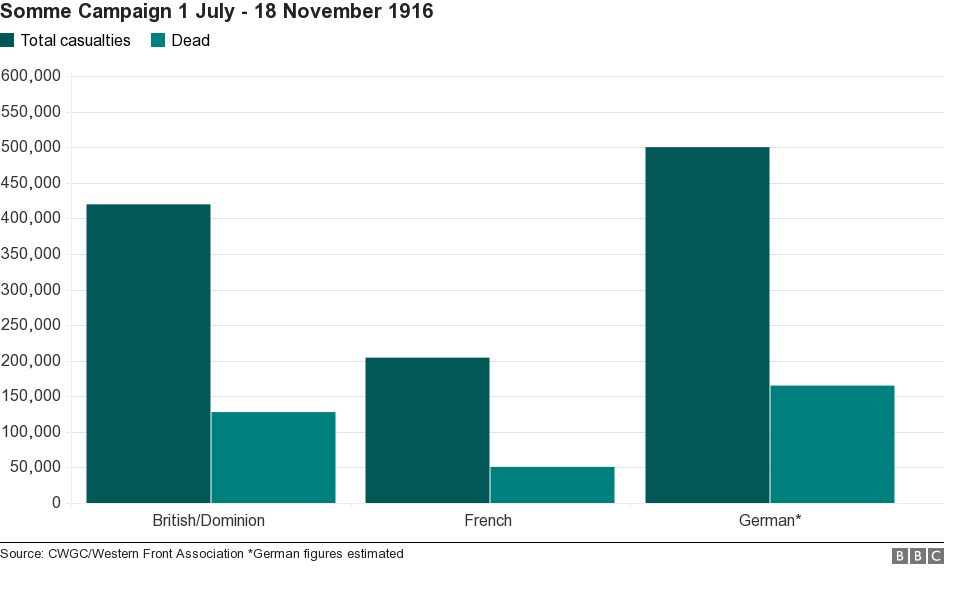

The Battle of the Somme

Began on 1 July 1916 and was fought along a 15-mile front near the River Somme in northern France

19,240 British soldiers died on the first day - the bloodiest in the history of the British army

The British captured just three square miles of territory on the first day

At the end of hostilities, five months later, the British had advanced just seven miles and failed to break the German defence

In total, there were over a million dead and wounded on all sides, including 420,000 British, about 200,000 from France and an estimated 465,000 from Germany

Find out more:

- Published1 July 2016

- Published1 July 2016

- Published1 July 2016

- Published1 July 2016

- Published30 June 2016

- Published30 April 2016