Tank at 100: Baptism of fire, fear and blood

- Published

The tank was first used in battle on 15 September 1916 at the Somme.

The tank, which would go on to dominate 20th Century warfare, first stormed on to the shattered battlefields of the Somme 100 years ago. Rushed into battle by desperate generals with barely any testing, its debut was a messy experiment with questionable results. A select group of young men were the first to feel its terrible influence and have their lives changed by it.

William Dawson came from Boston in Lincolnshire and was the eldest of four children. His father had drowned at sea in 1898 when he was 10 years old and as soon as he left school, Dawson went to work to support the family.

He found employment with a shipping company but had an interest in engines. In early 1916 he answered an advert in Motor Cycle magazine, in which the Motor Machine Gun Service (MMGS) asked for mechanically-minded recruits for intriguingly vague Army service.

By May he found himself transferred to the "Heavy Section" of the MMGS.

William Dawson was a keen mechanic and joined up after seeing an advert in a magazine

A few days later Dawson was locked into a training ground in Suffolk being given "a very serious talk explaining that the new project was so very very secret that he could give no details but that it was most important".

"The secret camp was very large, roughly circular and some three or four miles across. The perimeter was guarded day and night by 500 or more reservists fully armed with rifles and ammunition," he wrote years later.

"Early one morning just after daylight we were awakened by a rumbling and rattling with sounds of motor engines.

"In great excitement everybody rushed out of tents, just as they had slept, and there they were, the first of the tanks, passing our tents to the practice driving ground which we had prepared."

Barbed wire and machine guns had made battlefields impassable for infantry

Describing the appearance as "extraordinary", he added: "We immediately started to learn its mechanism and engine and commenced driving it round the course of three to four feet high obstructions."

The idea of armoured fighting vehicles had been around since Leonardo da Vinci but at the outbreak of World War One, practical battlefield machines were for most soldiers scarcely more than science fiction.

But as the fighting in France and Belgium bogged down into trench warfare, the concept gained supporters.

Having seen conditions on the Western Front as an official Army correspondent, Col Ernest Swinton was in a position to push for bulletproof tractors to crush wire and cross trenches.

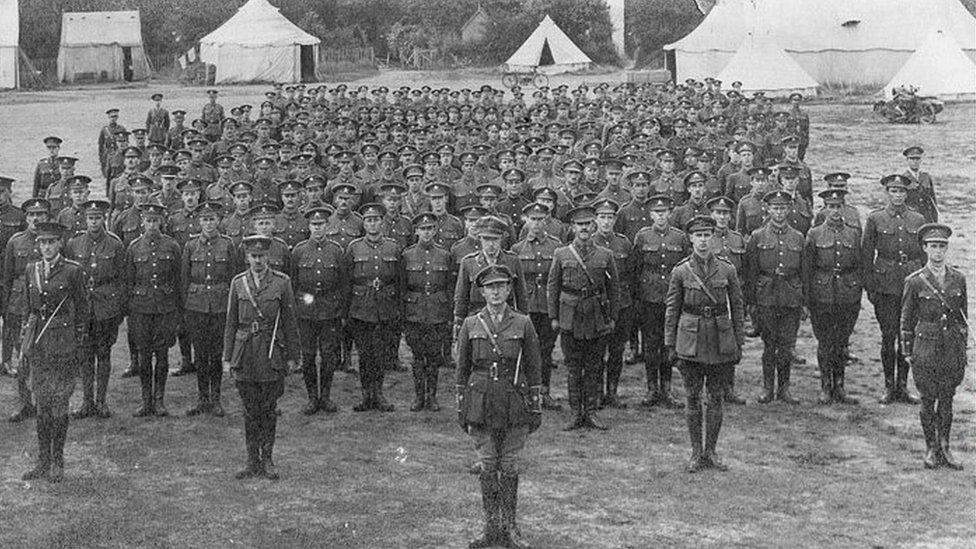

Some training was given to the first crews but tank war was an entirely new concept to the Army

He managed to attract support from Winston Churchill. then First Lord of the Admiralty. A "Landships" committee was formed in early 1915.

A machinery company in Lincoln was commissioned to build prototypes, with much of the design work done in a local hotel room.

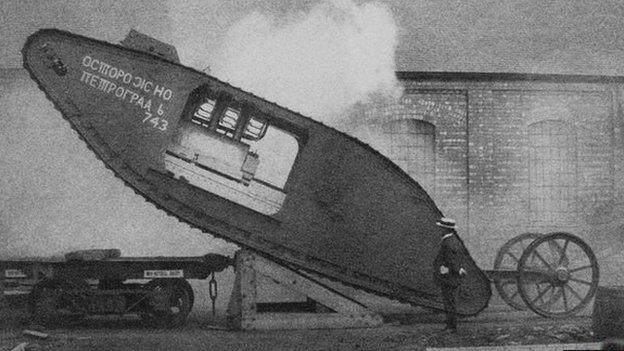

Tanks went from science fiction to steel fact in the space of six months. In late 1915 an 8m (26ft) long, 28-ton machine crossed a dummy trench system at Hatfield in Hertfordshire.

Lord Kitchener, the Minister of War, felt it was "a toy" and "without serious military value" but a representative of Commander in Chief Douglas Haig simply said: "How soon can we have them?"

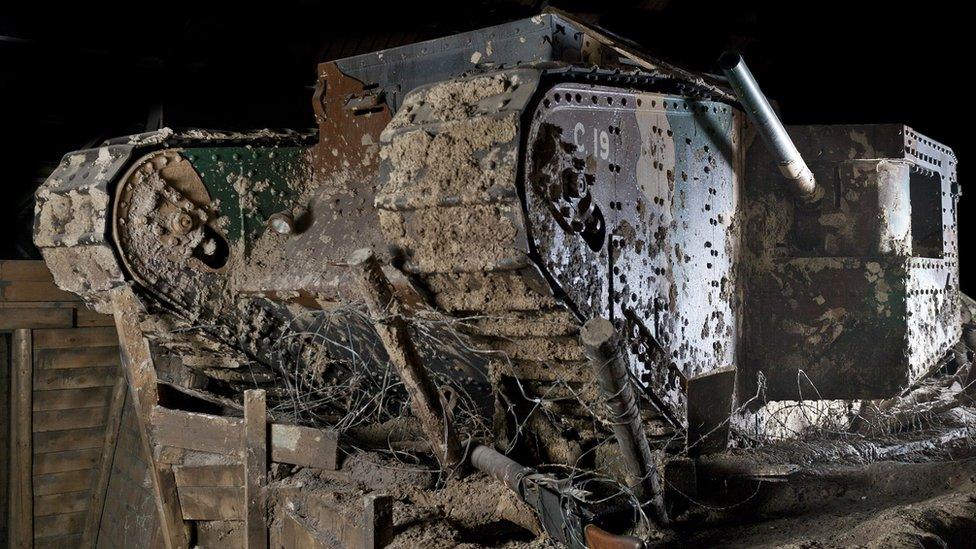

Tanks were designed specifically to cross the trenches and barbed wire of World War One battlefields

They made a huge first impression but were mechanically unreliable

By then planning for the Somme offensive was under way. Despite high hopes, the terrible losses of the first day and continued bloody fighting meant the need for a new weapon was greater than ever.

As with the machines themselves, an entirely new part of the Army, for an entirely new type of war, was thrown together in a matter of months.

Formed in March 1916 the Heavy Section Machine Gun Corps was commanded by Col Swinton. Suffolk's Elveden Camp hosted more than 500 men to crew about 50 tanks.

Rushed into service, men and machines were far from battle ready.

Basil Henriques had been involved in helping deprived children before the war broke out

Dawson said: "Our commander, Second Lieutenant Macpherson, was a fine and likeable young fellow but he like us had never been in an actual battlefield or in action before.

"The briefing and instructions regarding objectives were quite inadequate."

Basil Henriques was from another part of the social scale. Educated at Harrow and Oxford, he was appointed a lieutenant in April 1916, aged 25, and made a tank commander. But the same lack of training dogged him.

He said: "We had no training with the infantry, even at home, and the infantry with whom we had to fight had never heard of us until they actually saw us in battle."

By the time he arrived in France he had only worked with his crew once and had not used the guns on their machine.

One thing was clear to everyone: tanks were hellish to use.

Eight men squeezed into a tank cabin dominated by a hot, noisy and noxious central engine

The crew of eight was in a single compartment dominated by a huge engine. Tanks had no suspension and limited views outside. Every journey was deafeningly noisy, fume-filled and batteringly rough.

They were at the limits of technology. Engines were unreliable, armour was thin, tactics were guesswork. Communication was mostly by hand signal and pigeon.

And that was before anyone started shooting.

On 15 September 1916, the shooting would start. Almost every one of the 50 or so available tanks would be used to try to capture the village of Courcelette.

Masks were sometimes worn to protect against parts of the armour flying off inside the tank

Early indications were not good. Thanks to breakdowns, only 31 machines reached the start line.

The reaction of the German defenders to tanks varied. One trench garrison simply fled. Prisoners interviewed afterwards gave the impression that "German soldiers regarded them with some sort of superstitious terror.... till daylight disclosed their true nature."

Mostly the tanks were attacked with anything and everything. Machine guns, pistols, grenades and artillery.

Dawson recalled his machine blundered about the battlefield before meeting another of the new British tanks.

"Both it and ourselves came up against machine gun fire with armour-piercing bullets and while we had quite a few holes I counted upwards of 40 in the other tank."

The commander, Macpherson, left the tank to report to his superiors and was killed.

Filled with petrol and ammunition, tanks could quickly became fiery tombs for their crews

Henriques in tank C22 had also moved into the fight: "Squashing dead Germans as we went. We could not steer properly and kept losing the (guide) tape."

Guns blazed at the tank and he had to peer through a narrow glass slit in an attempt to see the enemy.

He said: "A smash against my flap in front caused splinters to come in and the blood to pour down my face. Then our prism glass broke to pieces, then another smash, I think it must have been a bomb right in my face."

With a tank full of injured men, Henriques withdrew.

Not everyone was so lucky.

Cyril Coles came from a family of New Forest millers but found himself conscripted

Cyril Coles, who was born in Canford, Dorset in 1893, enlisted in the Army in February 1916 and was a tank gunner in France by August.

Coles was in tank D15. Supposed to be one of three armoured vehicles, the others became stuck in shell holes before crossing the start line. D15 had reached the first German trench when it was hit be artillery fire.

The official history of the battle states: "The commander and his crew abandoned the burning tank but two of the men were then shot and killed and the others wounded."

Coles was one of the dead. Both men were buried beside the wrecked machine.

Staff at the Tank Museum researching the details of Coles' life, external believe he was one of the very first tank men to be killed in action.

The badly cratered ground, combined with the enemy onslaught, devastated the tanks.

About 12 machines had punched deep into the enemy defences but most of these were damaged. Only a few were still operational the next day.

Basil Henriques set some of the glass that injured him into a ring for his wife

Henriques had to have glass splinters removed from his face by medics. One piece was large enough to be mounted as a "stone" in a gold ring, which he gave to his wife as a memento of his brush with mortal danger.

The first fight of the tanks would be named the battle of Flers-Courcelette and, by the standards of the Somme campaign, it was a success. The new machines, though badly flawed, had shown potential.

William Dawson and Basil Henriques survived the battle and the war. They saw the tank develop into an ever more effective part of the Army, playing an important role in bringing victory in November 1918.

David Willey, curator at the Tank Museum, said: "The tanks had limited success on that first day in military terms, however their success in terms of psychology shouldn't be underestimated.

"The German troops were terrified of these machines and for the British, the tanks were a huge morale boost.

"This was a British invention, designed to save soldiers' lives, and it gave people hope, both on the front line and back at home."

- Published15 September 2016

- Published29 June 2016

- Published24 February 2014