Where are the blue plaques for black and Asian people?

- Published

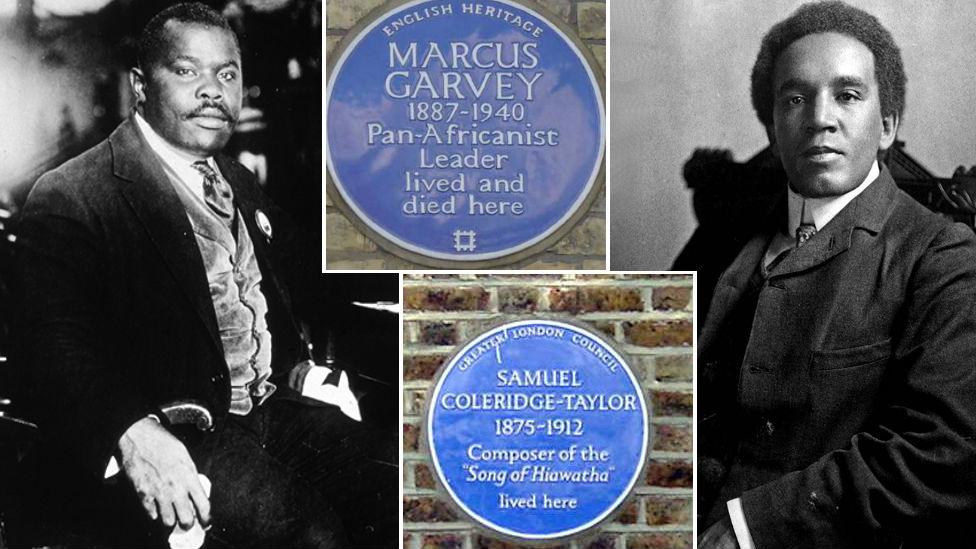

Marcus Garvey and Samuel Coleridge-Taylor both have plaques

At the same time a blue plaque was unveiled to mark the childhood home of football legend Laurie Cunningham it was revealed that in London, just 4% of the plaques honour black or Asian luminaries. But in such an ethnically diverse city, why are there so few?

According to the Office of National Statistics, London has above-average ethnic minority populations for the UK. These include African (7%), Indian (6.6%), and Caribbean (4.2%).

But there is not a proportional number of plaques and English Heritage has decided to take action.

Gus Casely-Hayford, a curator and cultural historian with Ghanaian roots, has been appointed the leader of a working group to try to redress the balance.

It will not award plaques itself, but will look for Asian and black candidates to put before the selection panel, which grants only 12 plaques a year.

Singer Elisabeth Welch lived at Flat 1 Ovington Court, just off the Brompton Road from 1933 until about 1936. She's pictured here in 1961

Dr Casely-Hayford says London is an "ethnic melting pot".

"We are linked through language, culture, political alliance and economic partnership to every part of the world," he says. "And peoples from places that we have touched, have found their way here, to not just make London their home, but to make London and this country what it is.

"We want to celebrate that rich, complex, sometimes difficult history, through the lives of those that truly made it."

Although the blue plaque scheme was set up in 1866, it was not until 1954 that the first to honour a notable figure of minority ethnic origin was installed - to Mahatma Gandhi.

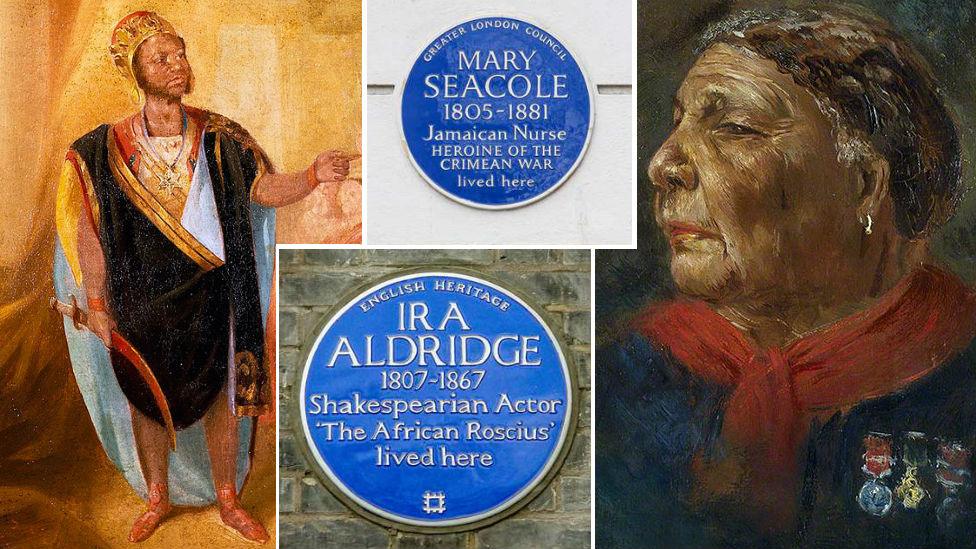

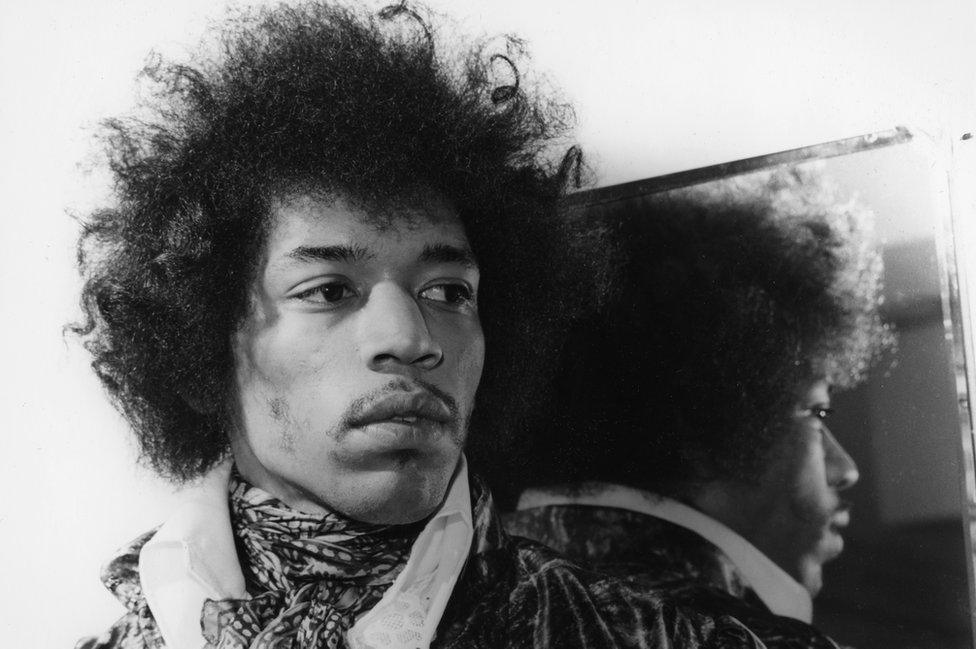

Other black and Asian people who have English Heritage plaques include Jamaican Crimea War nurse Mary Seacole, Chinese writer Lao She, external, Indian poet, Rabindranath Tagore, and American guitarist and song-writer Jimi Hendrix.

There are a variety of reasons for such a small proportion of plaques being for blacks and Asians, English Heritage says.

How to get a blue plaque

Ira Aldridge was the first black actor to play Othello on a West End stage. Mary Seacole was a nurse in the Crimean War

The scheme celebrates the link between significant figures of the past and the buildings in which they lived and worked. Here are the criteria:

They should be regarded as eminent within their own profession or calling

Their achievements should have made an exceptional impact in terms of public recognition or their achievements deserve national recognition

They must have been dead for 20 years

They should have lived in London for a significant period

The London building in which they lived or worked should still survive and must not have a significantly altered exterior

The building must be within Greater London but outside the City of London, which has its own scheme

Buildings with many personal associations, such as churches, schools and theatres, are not normally considered for plaques

These include the low number of public nominations fulfilling the blue plaque criteria and the lack of historic records establishing a definitive link between the person in question and the building in which they lived or worked.

Some prominent black and Asian people could be excluded from the English Heritage blue plaque scheme because they have already been honoured with plaques from other organisations on the same building.

Laurie Cunningham, who was the first British footballer to play for Real Madrid, was honoured with a blue plaque last week

For example, it initially appears Cesar Picton has been overlooked. A former servant, he became a coal merchant in Kingston-upon-Thames in the 18th Century and was wealthy enough by the time he died to bequeath two acres of land and a house - with a wharf and shops attached.

But although he does not have an English Heritage blue plaque, he does have a plaque from Thames Ditton and West Green Residents' Association and one from the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames.

Olaudah Equiano - a slave who went on to become a radical reformer and best-selling author, as well as the first black person to explore the Arctic - has a green plaque awarded by the City of Westminster and a memorial in St Margaret's Church at Westminster Abbey.

Dadabhai Naoroji, the first Asian MP, has a green plaque on Finsbury Old Town Hall in Islington and a second one erected by a local society.

This means none qualify for an English Heritage blue plaque on the same building.

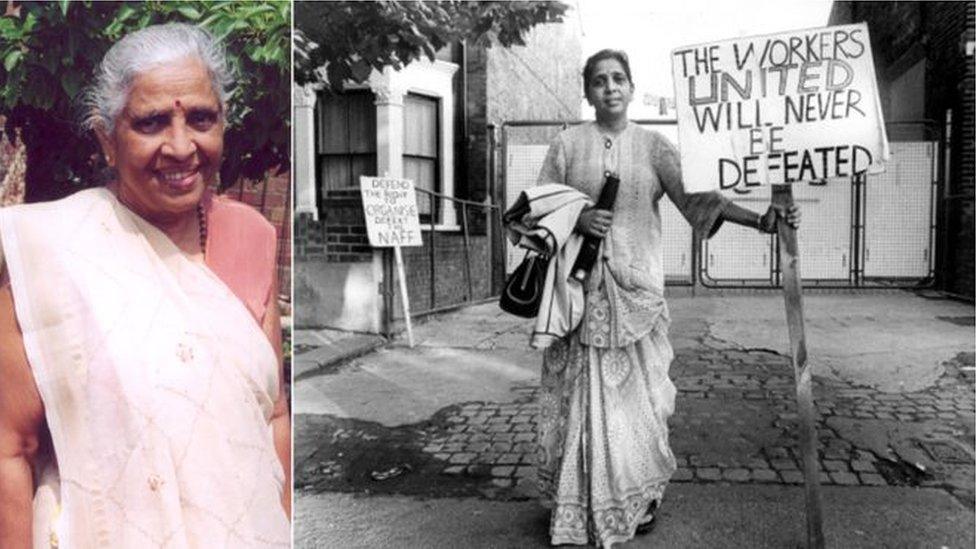

Jayaben Desai, pictured in 2001 and 1977, could be a candidate for a plaque in the future

Another reason why there are fewer black and Asian people honoured with blue plaques is the schemes' strict rule that people must have been dead for 20 years before being considered.

Many members of London's black and Asian communities arrived in the country after World War Two. Consequently many of the likely contenders for a blue plaque have either not been dead for long enough or are still alive.

This category would include Jayaben Desai, the prominent leader of the Asian women strikers in the Grunwick dispute in London in 1976. She died in 2010.

Similarly, Val McCalla, the Jamaican-born founder of The Voice, a national newspaper for the UK's black community, died in 2002. From humble beginnings in an East End flat, his newspaper grew into a major business and turned Mr McCalla into a millionaire. But he will not qualify for a blue plaque until 2022.

However, English Heritage is standing firm on this policy.

What are blue plaques?

English Heritage has run the London blue plaques scheme since 1986, when it had already been in existence for 120 years. Before that it was run by three bodies in succession - the (Royal) Society of Arts, the London County Council and the Greater London Council.

Outside London, many local councils, civic societies and other organisations run similar plaque operations.

"The 20-year rule is quite important to us," said spokeswoman Alexandra Carson.

"It gives us the benefit of hindsight and allows us to better judge their long-term legacy."

It also means dreadful mistakes can be avoided. The blue plaque panel, which meets three times a year, is led by Professor Ronald Hutton.

"The 20-year rule acts as a safeguard," he says. "The Jimmy Savile case lights up in neon the dangers of going on someone's pre-death reputation."

Another obstacle is the blue plaque schemes' traditional focus on establishment figures. This has resulted in a very low proportion of plaques for women or people from a working-class background. It has also served as a barrier to black or Asian people being recognised.

Jimi Hendrix, pictured in 1967, is one of the 33 black or Asian people to have a blue plaque in London

But now, says Anna Eavis from English Heritage, the criteria has evolved.

"[Since the scheme was established] our idea of which figures from the past are significant has changed," she says.

"While Laurie Cunningham was an incredibly gifted footballer who paved the way for many other black players… 50 years ago he would never have found his way on to a plaque."

Another issue is the fact that the plaques are as much about the buildings as about the people themselves.

A plaque is only erected if there is a surviving building closely associated with the person in question. Many black and Asian people faced racism and institutional barriers, and often lived outside of the official records, which makes it difficult to definitively link them to a specific building.

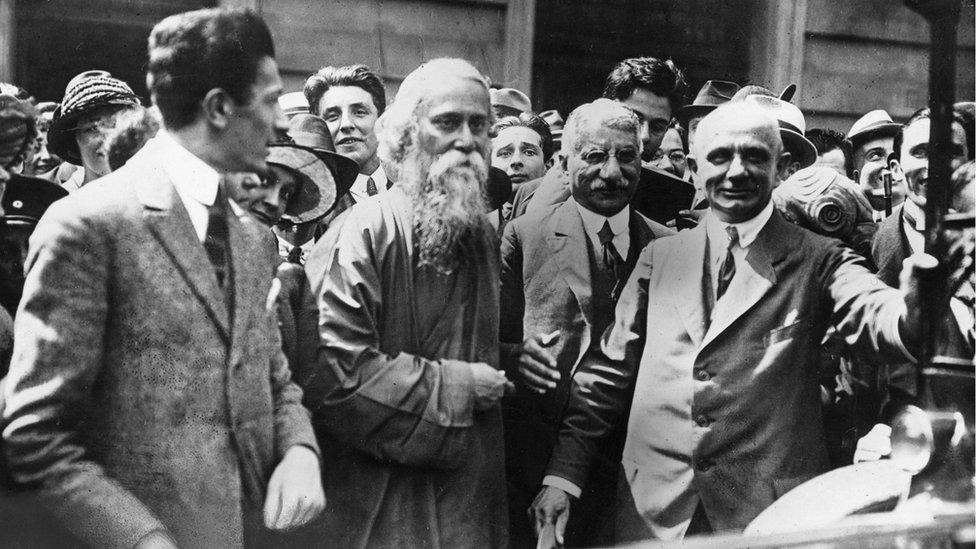

Indian poet and philosopher Rabindranath Tagore pictured in London in 1921

Historically, black and Asian people often lived in poorer areas which have since been redeveloped or demolished.

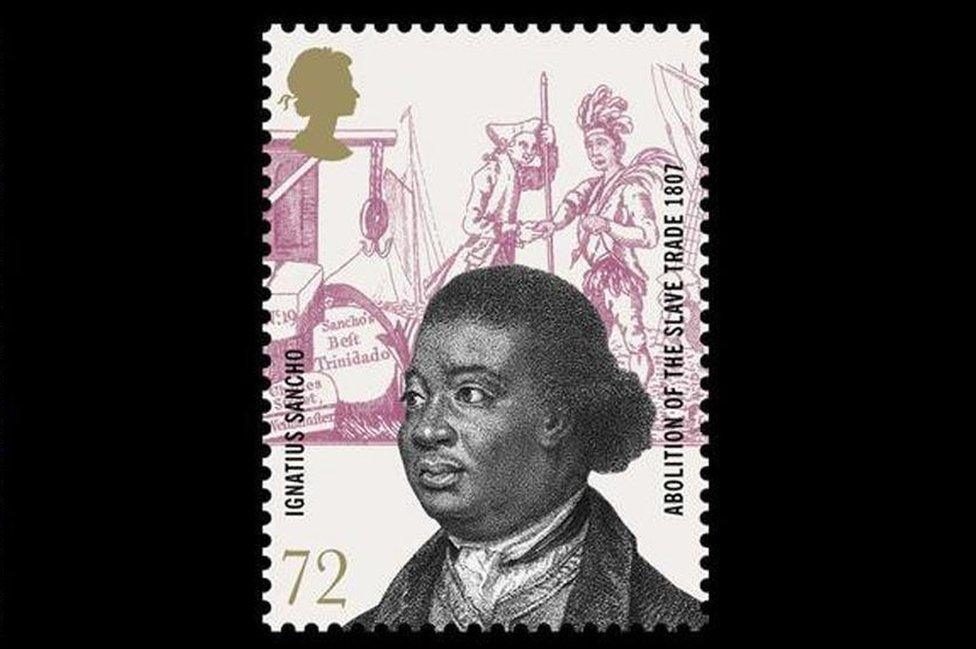

Ignatius Sancho, an abolition campaigner, composer, actor, and writer - who was the first known black Briton to vote in a British election - falls foul of this.

He has a plaque erected by the Nubian Jak Community Trust at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in the City of Westminster, which says he "lived and had a grocery shop near this site" and another on the remaining wall of Montague House on the south-west boundary of Greenwich Park, which commemorated the bicentenary of the abolition of the Slave Trade Act.

That would not be enough for an English Heritage blue plaque as there is no specific building he lived or worked in.

But English Heritage says it is determined to redress the balance.

Dr Casely-Hayford says he is asking the British public to help "in uncovering the stories of those unacknowledged heroes who helped make our great city what it is".

Yet, given the stringent criteria, those stories will need a significant amount of uncovering before the number of English Heritage blue plaques even comes close to representing the ethnic makeup of England's "melting pot" of a capital city.

Ignatius Sancho had a stamp in his honour but not a blue plaque

- Published21 September 2016

- Published29 May 2016

- Published20 February 2015

- Published27 February 2012