Why the Don't Knows aren't voting

- Published

The young, less affluent and less well educated are less likely to follow these arrows

In a world of fake news and alternative facts, what hope is there for the 15 million people in the UK who do not know enough to vote?

People like 36-year-old Lee Hall from County Durham, who does not "understand politics at all", for example.

"I wouldn't know who to vote for," he says. "I wouldn't know how to."

It is not uncommon for journalists, out gathering opinion, to find people who do not know, external there is an election on, which party is in power or who the prime minster is.

Martin Hearn, 31, from Middlesbrough, sees how lack of knowledge might put people off voting but when "information is so easy to get hold of these days that it does seem like a weak excuse".

But "people have lost faith in politicians and don't know who to trust or what to believe", he says.

And the "press and other media outlets" do not help.

In some cases, neither do election leaflets, delivered to your door and full of useful election "facts".

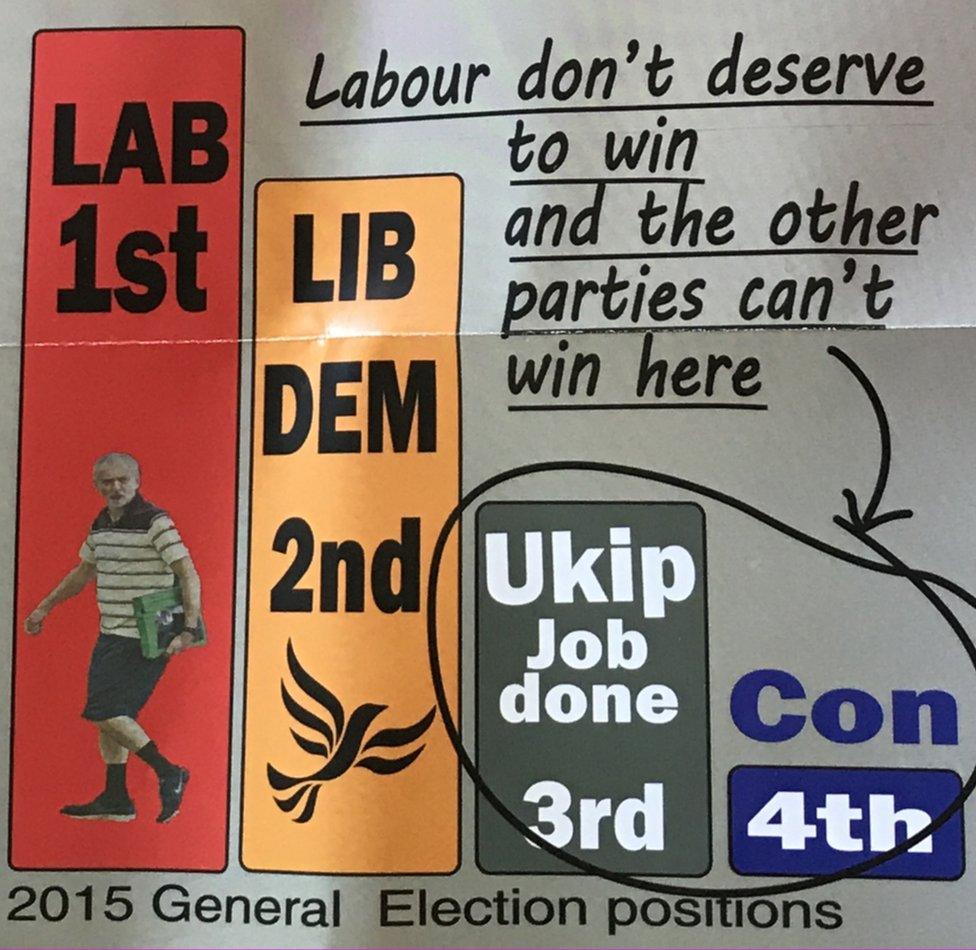

The Liberal Democrats are not alone in producing charts on leaflets which do not reflect the actual numbers

A leaflet from Redcar Liberal Democrat candidate and local councillor Josh Mason gives the impression his party came a much closer second at the last general election, locally, than it did.

It also makes the claim that UKIP "can't win" in Redcar - showing a grey bar half the size of the Liberal Democrat's yellow bar - although the two parties had an almost identical share of the vote (18.4% and 18.5% respectively).

Mr Mason excuses this by saying the "leaflet does not depict a graph".

"The image depicts the order in which the parties finished and is not, in fact, a representation of the number of the votes cast," he says.

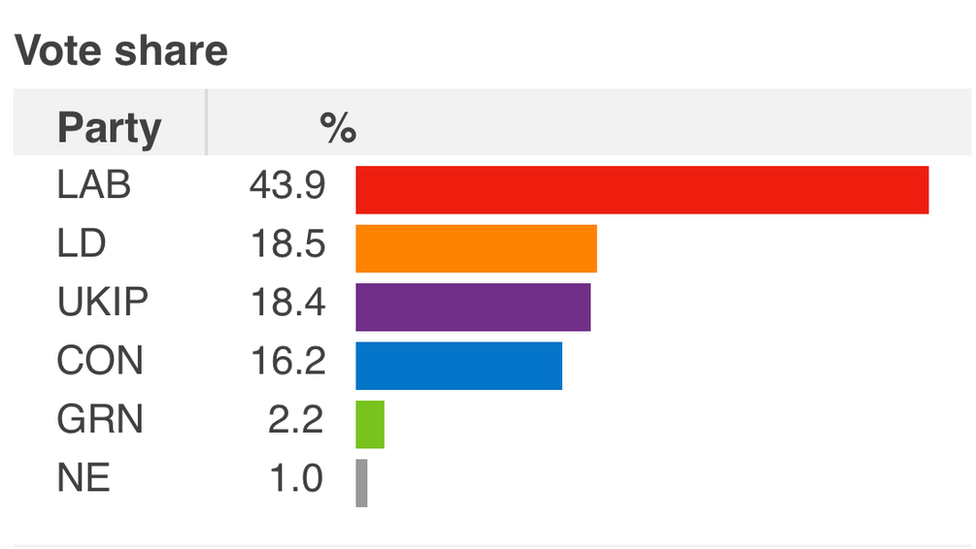

How the bar chart of Redcar's 2015 results should look

Lack of trust in sources of information - politicians, political parties, media and social media - is a problem, says Dr Stuart Fox from Cardiff University.

But trust has "never been that high", even among people who do vote.

What is "far more important" is lack of interest, he believes.

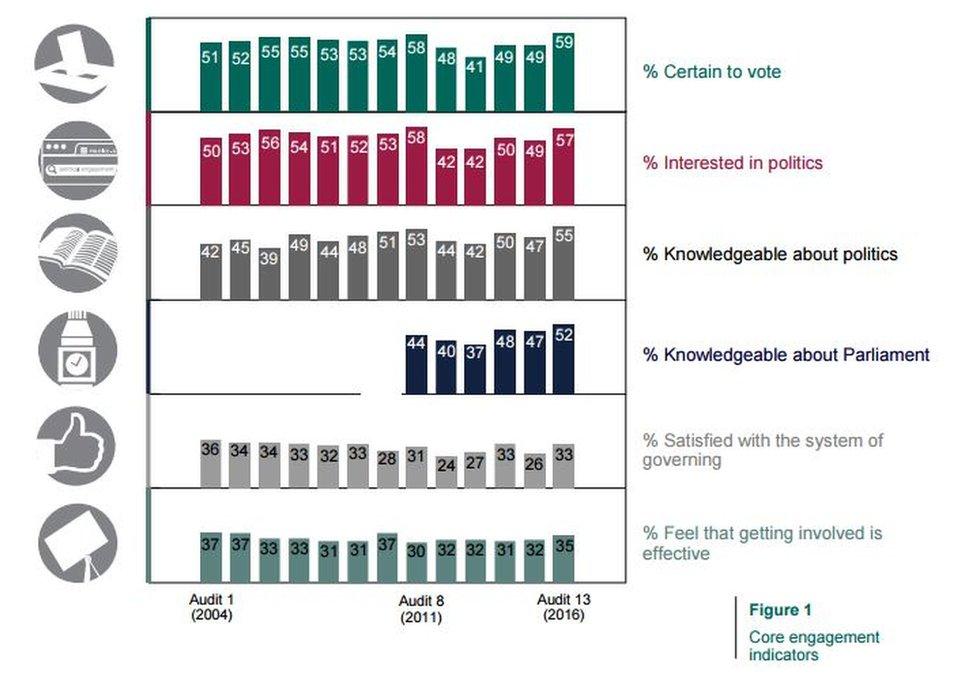

Data from political research and education charity the Hansard Society, external suggests older, white, more affluent and further educated people are more likely to vote.

They are also more likely to call themselves politically knowledgeable.

The research suggests the reverse is also true: younger, poorer and less educated people are less likely to vote and they claim lower levels of political awareness.

This Hansard Society chart on political engagement suggests those who don't vote are also less interested in and knowledge about politics

Dr Fox says "undoubtedly" there is a link between lack of knowledge and unwillingness to vote.

"They're too scared" to try to inform themselves, he says.

They can be interested but "quite daunted and intimidated by the whole process and can't find information that they feel is accessible or useful for them", he adds.

But, he cautions, some claim lack of knowledge when, in fact, they are just not motivated to take part.

In some countries, where voting is compulsory, motivation is beside the point.

North Korea, for one, claims a turnout of more than 99% and makes it easy by having only one candidate.

North Korea's leader Kim Jong-un won his last parliamentary election with 100% of the vote in his constituency

In more democratic Australia, voting is also compulsory - but at least there is a choice of candidates - and polling stations have "massive queues", says BBC librarian Leanne Nijemeisland, who moved from Melbourne to the UK.

"Not like here," she says, wryly.

"From a very young age you're taught how important it is to vote; there's this whole culture."

Non-voters "really, really aggravate" her and lack of knowledge is "not a good enough excuse", she says.

"You just have to take an educated guess.

"I don't trust politicians either, but you just have to go on what you think on the day based on the information you have."

Memorable Margaret Thatcher

"Do you know what year it is? Who the prime minister is?" A doctor would run through the standard list of questions to gauge whether a patient is confused.

But even those who are not have struggled to name some of the UK's leaders.

A North East hospital consultant describes how perfectly compos mentis patients often could not name John Major. Gordon Brown was also forgettable.

One No 10 incumbent - recalled clearly enough for medical reassurance - was often simply described with a shudder as "that man".

Another doctor - a psychiatrist - said patients would name Margaret Thatcher automatically, long after she had left power.

Jake Smith, a 22-year-old postgraduate student at Cardiff University, believes a debate on introducing compulsory voting to the UK is "long overdue".

He argues the compulsion would extend to the politicians themselves, forced "by electoral necessity to pay attention to those groups which previously did not vote".

Marking a "none of the above" option, if there was one, would give a voice to those who wanted to protest, on top of the option of spoiling a ballot paper.

Voting in Australia's federal elections has been compulsory since 1924

A campaign in Australia for this option on ballot papers has so far proved unsuccessful though Marianne Lloyd, who lives in Melbourne, might appreciate it.

Dr Lloyd feels "powerless" and frustrated at having to choose "usually between a number of highly incompetent morons".

"You're forced to weigh up who is the lesser evil in the grand scheme of things," she says.

"Bearing in mind that election promises are often broken and you can totally be wrong with what you thought was that lesser evil."

Although Australian voters must attend a polling station they are not forced to pick a candidate - but most do.

The proportion of "informal" votes - spoilt, blank or otherwise invalid - was just over 5% in the last federal election, the equivalent to the UK's general election.

There are those, like Dr Fox, who argue that introducing the same system in the UK would be a "massive improvement".

David Rumble from Durham, who is in his 20s, says he would "probably put a little bit more effort into researching what party to vote for" if the law made him.

But he thinks all politicians are "pretty much the same" and has no intention of voting if he does not have to.

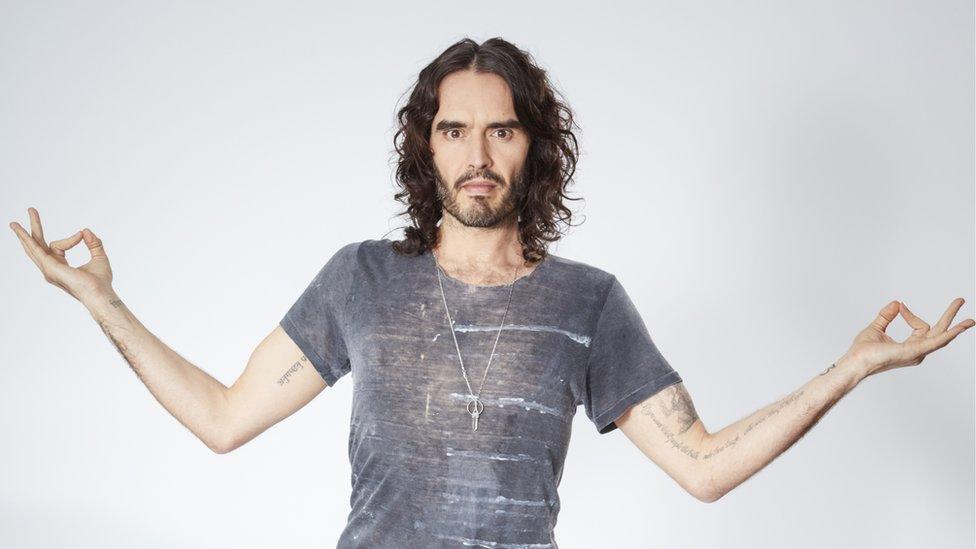

Russell Brand, once a high profile exponent of not voting, changed his mind at the last election and has now produced a video showing young people how to register to vote

Dr Fox thinks another solution to lack of engagement would be any political education in schools that is better and starts earlier than the "woefully inadequate" and "inconsistent" current offering.

Young people rarely think voting is a civic duty, he says.

Whereas their grandparents believed, even if you were ill-informed or did not care, "you were a citizen of this country, you had a responsibility to vote".

If the voting age was also reduced to 16 - as proposed in the Labour, Liberal Democrat and Green party general election manifestos - schools would have more of an incentive to teach politics, Mr Smith believes.

Although some question the "quality and impartiality" of political education in schools, it could be an effective way to boost knowledge, he says.

As Leanne Nijemeisland points out, in Australia it's "an exciting thing when you're at school, you're coming up to the age where you're allowed to vote".

And "if you don't go and vote, you don't get to moan about it later", she says.

- Published26 April 2017

- Published23 October 2013

- Published27 August 2013