Thankful villages: The shame of surviving World War One

- Published

Thankful villages are noticeable for their lack of war memorials

A thankful village is a community where everyone who went to fight in World War One came back alive. But what seems like it should have been a cause for celebration was actually a source of embarrassment and shame for many.

Edward and Ann Jameson experienced a lot of heartbreak.

Four of their 13 children died at a young age, then, after the outbreak of war in 1914, they had to watch four of their sons head off to fight the Germans.

It seemed unlikely they would all survive.

Hunstanworth was home to about 200 people when war broke out

Makepeace, 23 when war began, was wounded twice in 1916 and later hospitalised by influenza - the disease killed millions of people in 1918.

His youngest brother Joshua, 16 at the outbreak, joined up later and was struck by shrapnel which remained in his leg for the rest of his life.

But they and their brothers Michael and Ted all survived, along with a fifth villager, Arthur Taylor.

Hunstanworth, a cluster of farms, houses and a church high in the moors of County Durham, had become one of the lucky few - a thankful village.

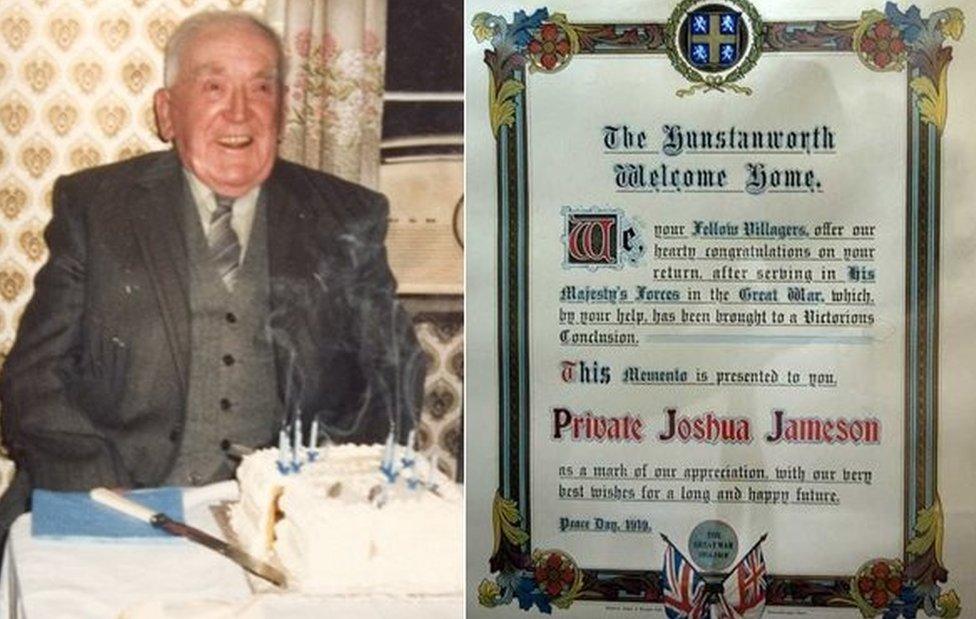

Joshua Jameson (pictured on his 90th birthday) received a certificate to mark his safe return

But as a blanket of grief shrouded thousands of communities, the thankful villages experienced a different emotion - shame.

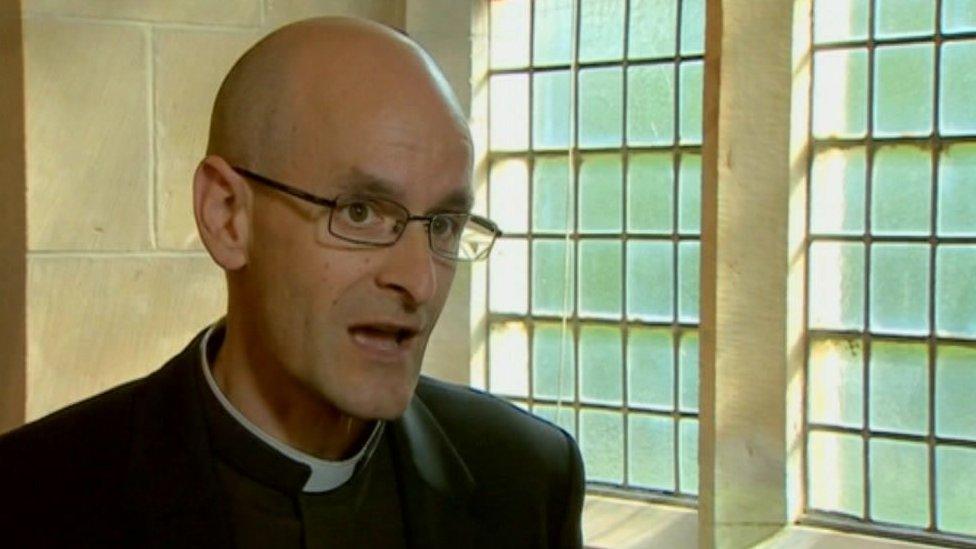

"They were surrounded by villages where people were not returning," said the Reverend Michael Hampson from the thankful village of Arkholme in Lancashire.

"For example, just up the road in Whittington the big landowning family there lost two generations in the war.

"That was typical around the country; the number who died was devastating.

"For the thankful villages, it was almost as if they had not joined in the sacrifice.

"They benefited from the peace after the war but felt like they had not paid the price."

That shame lasted decades.

The Reverend Michael Hampson said thankful villages like Arkholme were embarrassed about their lack of sacrifice

"We started talking about it around the millennium and still then there were people saying 'no, we should not shout about this, we do not want to blow our trumpet over our embarrassing privilege'," Mr Hampson said.

"There was a self-imposed silence and censorship; it was felt that it would be quite wrong to celebrate that as some kind of triumph."

Perhaps in part for this reason, it is only relatively recently that any attempt to list all the thankful villages has been made, the work being led by historians Norman Thorpe, Rod Morris and Tom Morgan, external.

The first task was to decide how to define what made up a "community" - a figure of about 16,000 was eventually established.

"We have always looked for a definite community, not just a few houses or an isolated farm with two or three cottages," Mr Thorpe said.

"A church, a school, a village hall, any sign of some social unit is what we look for."

There was a one in eight chance of being killed in the war

According to mathematician Michael Dunne-Willows, who has used the historians' research to help him try to calculate the likelihood a community would lose no men in World War One, it was always statistically probable there would be some thankful villages.

Of the six million British who went to war, about 700,000 died. Crudely then, there was about a one in eight chance of being killed.

Crunching the numbers further, statistician Mr Dunne-Willows tried to account for various unknown variables, making some assumptions and plugging the gaps with educated guesses.

One area of uncertainty relates to questions about the individual circumstances of soldiers and villages.

"Perhaps the village of residence played a role in which area soldiers were deployed to," said Mr Dunne-Willows.

"This would result in some villages having a higher or lower probability of being thankful, depending on the conditions.

"Perhaps the fact that often groups of friends, football teams and the like enlisted together played a role in survivability of smaller groups."

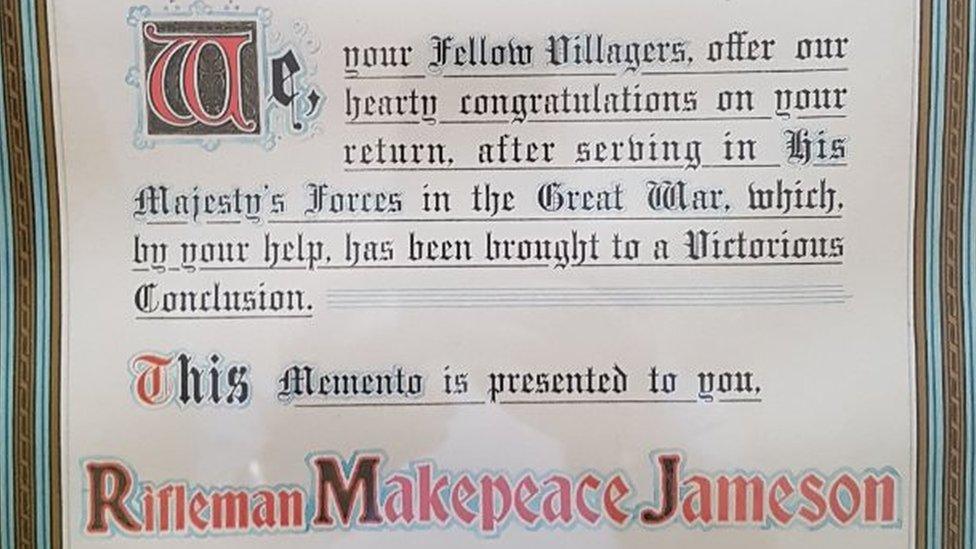

Hunstanworth presented certificates to its war survivors

After some clever mathematical manoeuvring featuring N values and D quantities, Mr Dunne-Willows has arrived at an answer for how many thankful villages he reckons there should have been.

That number is 22.

Out of about 16,000.

The number of thankful villages in England and Wales - none have been identified in Scotland or Northern Ireland - actually stands at 54.

However, fresh information can change the tally, for instance in the case of the Herefordshire village of Pipe Aston.

It had been considered thankful until 2012 when new research yielded the name of Pte John Deakin.

Deakin's place of residence was not noted but his parents were listed as living in Pipe Aston.

Might where people lived have affected where they were sent in the war?

Because he was aged 20 when he was killed in October 1917, Mr Thorpe said: "We must consider the possibility that John was living with his parents when he left home to go to war.

"Until we can verify or disprove these possibilities, we have moved Pipe Aston (off the list)."

Arkholme is on the list thanks to the 59 villagers out of 320 inhabitants it sent to war, who all survived.

No thankful village sent more, although in percentage terms Knowlton in Kent was dubbed the "bravest" village by a national newspaper for sending the highest proportion of residents.

The 12 who went - and came home - represented 31% of the 39 villagers, and the Weekly Dispatch presented it with an impressive stone monument.

Knowlton was presented with a monument celebrating its bravery

But of course just because everyone came back alive, this does not mean they were unaffected by what they had been through.

A collection of coins belonging to the blacksmith of Catwick is testament to this.

All 30 men who went to war from the East Yorkshire village gave John Hugill a coin he nailed to his doorpost below a horseshoe.

All 30 came back but, as noted by writer Arthur Mee, who coined the term thankful village in his 1930s series of King's England books, one man called Joseph Grantham "left an arm behind".

Catwick blacksmith John Hugill nailed a coin below a horseshoe for each man who went to war

John Hugill cut a notch in one of the coins to represent the lost limb.

During World War Two, Catwick's villagers and blacksmith performed the same coin trick.

"If it worked in one world war why might it not work in the second?", said John Hugill's grandson, also called John Hugill, who is now the owner of the coins.

"People were fairly keen to keep the tradition up."

One of the coins was notched to represent the soldier who lost an arm

And somehow there was the same outcome: all those who went to war against Hitler's Germany and its allies came back home.

So Catwick is one of an even more elite group of villages, those said to be doubly thankful.

This list numbers just 17, although Mr Thorpe and his colleagues said further research was required.

For example Hunstanworth is not on the doubly thankful list but it might well have a case to be.

Villagers John and Ellen Hunter certainly believe so.

Mr Hunter can remember all those who went from the village to serve in World War Two, which is to say both of them.

And both men returned alive.

The Catwick coins and horseshoe are kept by John Hugill's grandson in a carrier bag

There is some debate about a third man, however, a flight engineer called Jim Cook who was never found after the plane he was on crashed.

He was married to Mr Hunter's neighbour Barbara, but though he spent a lot of time at her Hunstanworth house, his actual home would appear to be the airbase where he was stationed.

It is the sort of situation encountered numerous times by the researchers.

But there is one simple factor the historians and statisticians do agree makes a village thankful.

Luck.

"We have studied this from several aspects," Mr Thorpe said.

"The only conclusion we can reach is that the safe return of all those who served from a particular village was simple chance, like casting a die."

There is a now a plaque in Arkholme celebrating its status

With the passage of time and the consequent change in attitudes, these thankful villages no longer feel the same shame.

In 2013, a group of motorcyclists toured the nation's thankful villages, presenting plaques celebrating their status.

Mr Hampson said changes to Remembrance Day had helped.

"It used to be about each village remembering its dead and the individual sacrifices it made," he said.

"But as time went on, new generations no longer remembered those who had been killed.

"Now it has become a much bigger thing about remembering the folly of war, the one day when everyone is united against the tragedy of it."

- Published10 November 2011

- Published13 November 2014

- Published27 February 2014

- Published27 July 2013

- Published11 November 2011